Could the end of the NJ county line doom county political machines? Some wonder | Stile

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The party line, a routine fixture of New Jersey primaries for nearly 80 years, appears to be doomed to the dustbin of Garden State political history.

But major questions now loom: Will the demise of this quirky, only-in-New Jersey ballot feature truly drain the power of the county chairs and the unelected party bosses? Will it make New Jersey campaigns more democratic and competitive?

Or will members of the old guard, rooted in tradition, simply adapt and wield their old power under a new system? Will the closed-door clubhouses in Middlesex, Bergen, Camden and Hudson counties still hold the levers of power in Trenton?

These are among the looming questions as the political community plunges into an unknown future, and quickly. Only one thing is for certain: The state’s politics have been changed forever.

Unless a federal appeals court rules otherwise in the coming weeks, the days of a primary ballot where candidates endorsed by the county parties are bracketed in one efficient column or line will no longer be in use for the Democratic primary on June 4.

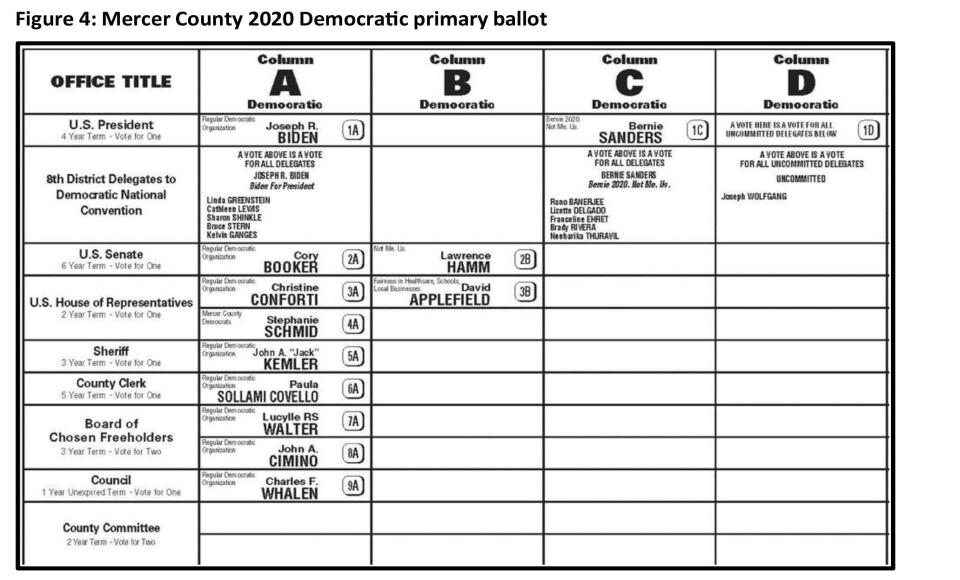

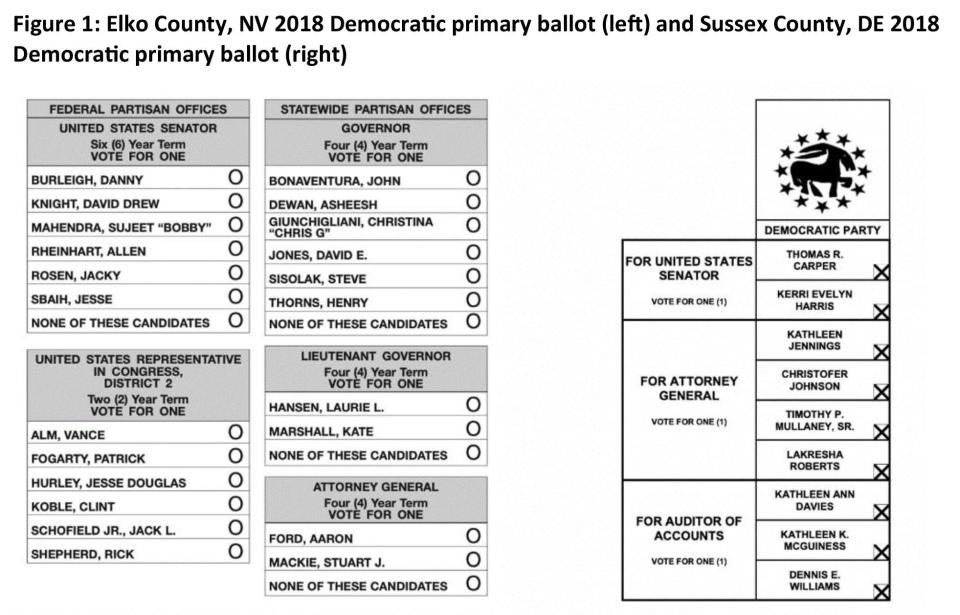

A March 29 ruling by U.S. District Judge Zahid Quraishi ordered the line replaced by a block ballot design, in which all candidates for each office are grouped together on the ballot, a method used in the 49 other states. The order does not apply to the Republican primary.

“We used to rest on our laurels and say, ‘Hey, vote Column A for Biden on down to Murphy on down,’" said Michael Suleiman, the Atlantic County Democratic Party chairman. “We won't have that luxury anymore.”

More Charlie Stile: NJ's ballot line system is dead — the 'magnitude' will reverberate across politics

Block ballots begin to feel inevitable

Defenders of the line system still cling to hopes that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit in Philadelphia will overturn Quraishi’s decision in the coming weeks.

But by the end of last week, all of the state's county clerks who were named as defendants in the lawsuit had dropped out of the case, choosing instead to comply with the order and draft the new block ballot for the primary. Two Democratic County parties, Camden and Middlesex, are continuing with the appeal.

Quraishi's injunction has also caused some Republican clerks to consider ditching the line, even though the order doesn't apply to GOP races. The Burlington County clerk took the liberty of removing the line ballot for Republicans, prompting a lawsuit last week by the county's Republican Party.

Meanwhile, many politicians from both parties now feel that the block design is inevitable — if not completely by this year’s primary, then in the coming election cycles. Quraishi’s order, many expect, will stand as a historic turning point, regardless of what the appeals panel decides.

In recent days, the defenders of the old-guard system say the line served as a moderate, inclusive force, allowing the political leaders in each county to screen out extreme or fringe candidates whose values didn’t align with the party establishment.

But reformers and foes of the line say it became a powerful, anti-democratic cudgel used by party bosses to keep incumbents in line and discourage challengers and dissenters. Candidates who bucked the system often found themselves “off the line,” or cast off in “Ballot Siberia," a remote corner of the ballot that rarely produces winners, studies have shown.

“For those not involved in party politics, the battle over party lines may seem remote, even childish. But make no mistake: This fight is important to every citizen," said Parsippany Mayor James Barberio, a Republican who won the 2021 primary despite being denied the Morris GOP line.

“The power of the line allows party bosses to shape local government decisions and decide who is elected — and not elected." said Barberio, who went on to win the mayor’s office that November.

Last week: Third Circuit Court of appeals does not stop redesign of NJ primary ballots

Now the block ballots will liberate many candidates. Without having to woo party leaders for a coveted spot on a line, candidates will be free to act with more independence from their county leaders. The days of being rubber stamps for the party machines are over. They can vote for the broader interests of their districts and the state, not just the narrow, self-interests of the county parties.

“I think people will start to speak up and you'll see more people entering contests," said Julia Sass Rubin, a Rutgers professor who has helped lead the crusade against county machine power in recent years and whose studies on the impact of the line on elections served as key evidence in Quraishi’s order. “You will see more pushback … We'll see more bravery.”

Deborah Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, believes dismantling the line will open the door to more opportunities for women and people of color to run for office. New Jersey's number of elected women places places it as 23rd among the states, far behind other blue states like Oregon, Colorado, Washington, California and Vermont (although higher than New York and Massachusetts). Walsh attributes New Jersey's middling ranking to the state's reliance on the archaic line ballot design.

“We have this system that has closed down opportunities," Walsh said. “For newcomers, if you're not sort of hand-selected by the party leadership, it is just that much harder to break into the system.”

Many expect NJ party machines to endure, adapt

Yet others believe that the party leaders are not going to go quietly and will find new ways to maintain their grip on the political structure.

“People who have [run] the state will do anything to retain that power," said state Sen. Holly Schepisi, R-Bergen, who supports eliminating the line. Their control of patronage and other spoils of power “are too important and generate too much income to the powers that be to not do whatever is needed to ensure that they win," she said.

Schepisi argued that wider campaign finance reforms are needed to make sure the switch from the line to a block ballot system succeeds. She said the new system is vulnerable to political mischief financed by deep-pocketed interests.

Without the line, a party with designs on capturing a competitive swing district in the general election might try to take out the district incumbent by running a phony “phantom” candidate in the primary.

Others speculate that party leaders will find innovative ways around the new block system to be sure that voters are made aware of the party endorsement inside the privacy of a voting booth. County-endorsed candidates could be singled out with a special color code or perhaps with a star indicating the endorsement. Quraishi’s ruling didn’t prevent the use of party slogans in new ballot designs.

Top legislative leaders from both parties repeated their call last week to explore and enact new reforms to the balloting. LeRoy Jones, who is chairman of the state Democratic Party and the Essex County Democrats, said the study would allow lawmakers to explore issues left unaddressed by Quraishi's ruling. Should the state move to a uniform system for all 21 counties instead of the patchwork now in existence? Should candidates who file joint petitions be bracketed together in the office block format?

"As I have stated several times now, I do not oppose the block ballot design,'' he said in a statement. "Good candidates (and parties) must do the work to win their elections, no matter what the ballot looks like. I also continue to support an organizational right to associate, something acknowledged and reinforced explicitly by the Judge’s order."

Parties still have other institutional advantages, like campaign war chests, that they can put at the disposal of endorsed candidates. Their alliances with special interest groups, such as unions, and the network of county committee members still make endorsed candidates formidable machines, even without the line.

“I would caution my progressive friends that this idea that you get rid of the line and all these incumbents are going to topple is silly," said Suleiman, from Atlantic County. “You still have fundraising advantages. You still have party support. You still have name recognition.”

Some point out a potential irony for progressives clamoring for reform: With the loss of the line, county machines will need to raise and spend more campaign cash in primaries to elect endorsed candidates.

Still, Suleiman said he’s resigned to work within the new ballot block system if the court ultimately strikes down the line for good.

“I just say, 'Let's rip the Band-Aid off and get moving one way or the other,’" he said. “We've got to make it work. If we have a ballot design, clearly the parties will have to work harder to get the message out.”

Charlie Stile is a veteran New Jersey political columnist. For unlimited access to his unique insights into New Jersey’s political power structure and his powerful watchdog work, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: stile@northjersey.com

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NJ county line ballots: Could county machines be in danger?