'Communities under siege': Cincinnati accused of using federal housing funds to segregate

Cincinnati city leaders misled federal housing officials in an effort to cram more subsidized housing in the city's poorest, Black neighborhoods, a federal complaint argues.

Ten West End advocates, including community council leaders, property owners and a former city council candidate, submitted the complaint Monday to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, also known as HUD. They allege the city misused federal funding for years to steer low-income housing to these communities. Cities are supposed to spread out these projects to promote area income diversity under the Fair Housing Act and federal regulation.

As a result, they say, efforts to revitalize the neighborhoods stagnated, leaving residents to cope with the ills common in low-income areas of poverty. Residents who live in these places suffer from food insecurity, high blood pressure, lower life expectancy and the city's highest rates of gun violence.

The group wants the city to stop funding income-restricted housing in the West End and other poor, Black neighborhoods, and instead direct these projects to Cincinnati's wealthier, white areas. They also want the city to fund a private, nonprofit housing agency to both monitor the city's and county's use of federal public housing funds and help low-income tenants find units in desegregated parts of town.

The Enquirer provided the complaint and statement of evidence to city spokesperson Mollie Lair on Monday. She said Wednesday the city had no comment.

Complaint says low-income housing too concentrated in Black neighborhoods

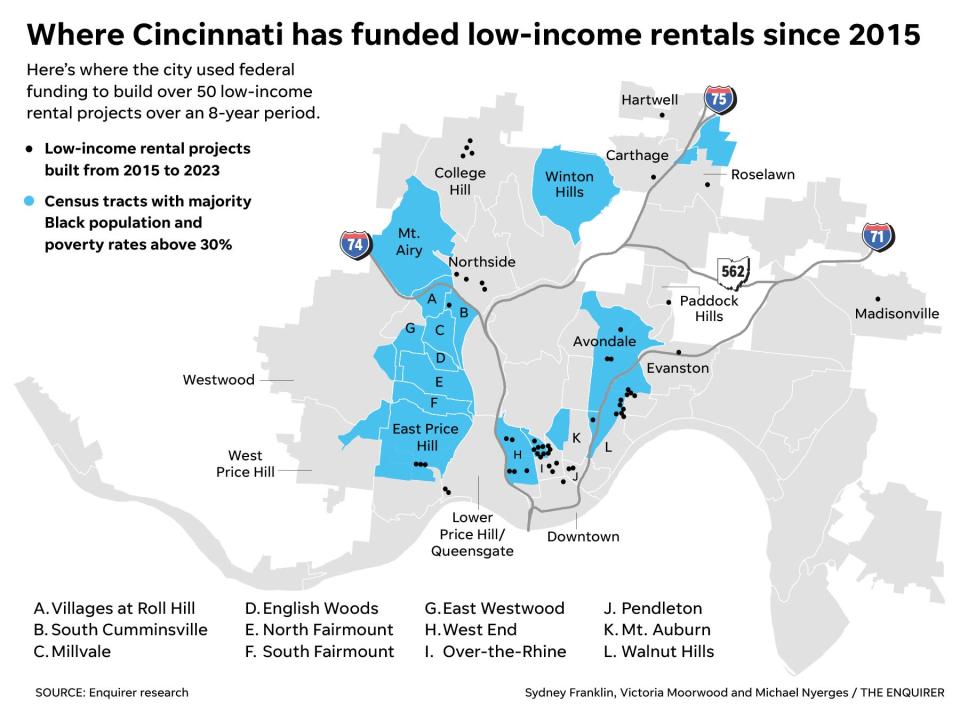

Nearly 82% of the city’s low-income housing is crowded into over a dozen majority-Black neighborhoods, per the complaint. Census tracts within those neighborhoods contain poverty rates above 30%, according The Enquirer's census-backed Neighborhoods Report Card.

The complaint also alleges that, in a 2020 report required by HUD, the city failed to identify some of these neighborhoods as Black in order to build more subsidized housing there.

Concentrating low-income housing in these neighborhoods could be considered a civil rights violation since it can perpetuate segregation and limit housing choice. Under federal law, cities are discouraged from approving funding for new projects in impoverished minority neighborhoods already inundated with low-income housing. This defies the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which obligates cities to instead work to integrate communities.

West End Community Council president Chris Griffin says the complaint is a last resort. Despite appealing to City Council and Mayor Aftab Pureval, both with statistics and harrowing stories about life in the West End, the city continues to direct funds to subsidized rentals in his community.

"I can tell you what’s good and bad for my neighborhood,” he said. “At the same time, I know we have less than 10,000 residents and our voting percentage is down. I don’t think that’s enough reason not to listen to somebody like me.”

The firm behind the complaint, Dallas-based Daniel & Beshara, P.C., has a history of representing similar cases, including a U.S. Supreme Court victory for the Fair Housing Act in 2015. Lead litigator Laura Beshara called Cincinnati’s actions "way beyond any premeditated carelessness."

"It's a race to the bottom in Cincinnati in that the city is solely focusing on building out communities that are all or almost fully subsidized," she said.

'Somebody looked the other way'

The city and developers use federal funding to build low-income housing through several sources including:

Community Development Block Grants, known as CDBG funds, are used to rehabilitate housing, assist homeownership and improve infrastructure, among other things. HUD typically gives Cincinnati over $11 million annually, which the city uses a portion of to finance between four to 12 projects each year.

The HOME Investment Partnerships Program is usually used by cities to rehabilitate or build new low-income rentals or homes in partnership with area nonprofits. It can also be used for low-income rental assistance. HUD usually doles out upwards of $3 million to Cincinnati each year to fund this work.

Low-income housing tax credits, administered by the state's Ohio Housing Finance Agency, provide developers or landlords with tax benefits ahead of construction. Mayors and city councils are encouraged to support project applicants with letters. Since 2020, 15 Cincinnati projects have been awarded $14.3 million in annual tax credits, according to data from the Ohio Housing Finance Agency.

According to the complaint, Cincinnati's administration knowingly approved federal funding from these various programs to steer affordable housing to low-income, Black communities, and therefore away from white, non-Hispanic neighborhoods where affordable housing is typically harder to build.

From 2019 to 2021, for example, more than 80% of affordable housing projects were built in the West End, Walnut Hills and Avondale − historically Black communities with poverty rates above 40%. Lawyer Mike Daniels described these neighborhoods as "communities under siege" by the local government.

"What Cincinnati has done to a very thorough degree is use a variety of programs to bring about the same result: build more publicly-assisted housing," Beshara added. "They've done this almost exclusively in Black communities despite the city's incredibly high degree of segregation."

According to the city's five-year consolidated plan submitted to HUD, many of these communities are targeted specifically for CDBG funds because they are places where the city is strategically reinvesting money and resources. HUD's Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Guidebook, updated every five years, cites improving area access to jobs, transportation, education and the need for private investment, retail and grocery stores as part of community revitalization plans.

Federal money can also be used by cities to promote homeownership in renter-heavy communities. The complaint claims Cincinnati has historically failed to do this, furthering the city’s racial wealth and home ownership gaps.

What Cincinnati does is not unusual, according to HUD data.

"The checks and balances are supposed to be in place to stop this from happening," Galen G. Gordon, who owns a single-family home in the West End's Betts-Longworth Historic District, said. "Somebody looked the other way and checked the box so we could say we have affordable housing in Cincinnati."

Is this illegal?

Not only could the city be held accountable for violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits the use of federal program funding to discriminate based on race, but it could also face violations within the Fair Housing Act.

In addition, the city could dually be condemned for not following multiple federal regulations including enacting ordinances, policies and permitting rules that restrict or deny housing opportunities because of race.

City governments aren't the only entities responsible for upholding fair housing standards. Since they jump-start projects, developers, real estate agents and eventually landlords must adhere to them, too.

Kim McCarty, 56, a West End homeowner of nearly 30 years knows this: "Make no mistake, the alleged critical civil rights failure falls squarely on the city," she said, "but it is the symbiotic relationship between the area’s low-income housing developers that solidifies segregation."

Two decades of saying 'We have a problem here'

Over the past two decades, city officials have publicly acknowledged Cincinnati's issue with concentrating poverty in Black communities multiple times. In 2001, former Mayor John Cranley's administration passed an impaction ordinance meant to more strictly govern the city's approval process for low-income housing tax credits and use of federal block grants.

That ordinance, still under effect according to the complaint, calls for the opposition of new projects in poor, Black neighborhoods unless they are dedicated to serving the elderly.

In 2012, the city published its community-driven 10-year plan for Cincinnati, which outlined goals to evenly distribute affordable housing throughout all neighborhoods and eventually approve public funding for mixed-income-only projects.

The city again cited concentration in a 2014 report to HUD, listing it as a barrier to fair housing.

As recently as January, Mayor Pureval announced during a press conference that reforming the city's zoning code could help give all residents more housing options, reduce rents and stop concentrating poverty. The rezoning proposal is currently under a community engagement period until it is expected to be voted into law this summer.

Despite all of this, the number of low-income housing projects in the West End alone has nearly doubled since 2012.

Has this happened in other cities?

Successful litigation accusing cities and counties of concentrating poverty is rare, but the issue has gone to the highest courts in the United States.

The most well-known case, still ongoing today, started in 1966 when six Black tenants of a Chicago public housing project filed a class-action complaint and a lawsuit against the local housing authority. The result of it was the establishment of the country's first-ever nonprofit to help voucher tenants find desegregated housing options.

Another case in the 1980s brought by thousands of low-income Black residents against nine West Dallas suburbs, the city's housing authority and the nation's HUD also led to the creation of a similar fair housing organization and a $22 million fund to create more units in predominantly white areas of Dallas.

In 2009, New York's Westchester County was sued for misrepresenting its efforts to end segregation in white communities while securing federal housing funds. Along with a hefty settlement, the county was forced to spend $52 million to develop 750 affordable housing units in neighborhoods with small Black and Latino populations.

Six years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that, under the Fair Housing Act, people can challenge government policies that have a discriminatory effect without having to prove discrimination was the intent. That high-profile, precedent-setting case came to the Supreme Court thanks to Daniel and Beshara, the lawyers who filed West Enders' complaint.

Homeowner Noah O'Brien, 44, noted the importance of getting expert, out-of-state legal counsel for a complaint of this magnitude.

"That's what makes this case different," he said. "The city has to know that this is not a little thing, and it's not going away... It's a lot harder to disregard [our lawyers] the way they have disregarded us."

Recently funded projects in the West End

Adding more affordable housing isn't inherently bad. Cincinnati needs almost 50,000 more units to serve roughly the city's 84,000 low-income individuals, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Local officials have made it clear they are committed to addressing this. But it matters where those units are built.

In Cincinnati’s West End neighborhood, where 78% of residents are Black, over two-thirds of all housing is reserved for low-income people, according to Enquirer research. Development on these low-income rental units hasn't slowed there. Slater Hall, a permanent housing complex for formerly homeless individuals with addictions or mental health disorders, wrapped construction earlier this year in a census tract that already houses 22 other income-restricted buildings and no homeowners.

West End Community Council leaders begged city officials not to move forward with Slater Hall, emails obtained by The Enquirer reveal. City Council announced it would use money from its new Affordable Housing Trust Fund to build the complex on the same day it pledged these funds wouldn't further concentrate subsidized housing.

Neighborhood leaders again clashed with the city and the Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority when the authority wanted to add more low-income housing units in the form of a federally-funded Choice Neighborhoods community.

In 2023, the city approved federal funding for more affordable housing in West End, Over-the-Rhine and East Price Hill.

The cost of segregation

Cincinnati's segregation dates back to its founding, but the federal complaint shines a light on how current affordable housing policies may make the division between Black and white residents a matter of life and death.

For the first time since he started coaching the program eight years ago, Larry Collins had to cut his older baseball players' summer season short last year due to an increase in shootings near their practice fields across the West End and neighboring Queensgate.

"A few kids are fearful about where we practice. We need a better life for our youth," the West End coach said, adding that the city's concentration of low-income housing developments has left kids with fewer options for safe play.

The Enquirer has reported that segregation and poverty concentration are correlated with higher crime and violence and dips in graduation rates for teens, among other negative outcomes. The best-case scenario? People live with a lower quality of life compared to nearby white neighborhoods. The worst case? Children die.

De’Asya Allen, a 22-year-old neuropsychology student, witnessed the aftermath of a shooting outside her high school graduation party years ago. And last November, her neighbor's 11-year-old son − a classmate of Allen's young sister − was shot and killed.

“No one is safe down here. No one has an exemption,” she said. “It doesn’t matter who you are or how long you’ve been down here. Bullets don't have names on them."

Melvin Griffin, 71, was displaced from his West End rental of 27 years after it was redeveloped into very-low-income housing. He now lives in Roselawn − a roughly nine-mile drive away from friends and family − where he's overwhelmed with the upkeep of his single-family home and worries about his safety. Just last week, a Rumpke driver was shot and killed blocks from Griffin's house.

The financial future of a neighborhood is also at risk as wealth gaps also widen. Outside, private developers are less likely to build in areas with lots of low-income housing, so it's up to nonprofit developers or community development corporations to shoulder the burden of building.

'The city is going to get sued.' What's next?

HUD could take weeks or months to review the complaint and conduct a fair housing investigation into the city's actions. Whether or not the agency charges Cincinnati with discrimination, the lawyers are confident that the residents behind the complaint can take the issue to federal court.

“For context, it’s not like we’re hiding anything,” Chris Griffin said. "We told [the mayor] last year that the city is going to get sued.”

A federal investigation isn't all the group is seeking. In the West End and neighborhoods like it, Griffin and the others want the city to:

Stop approving zoning changes or providing tax abatements for low-income housing credit projects.

Use funding and resources to build playgrounds, recreational facilities and improve infrastructure while trying to lure retail and grocery stores typically found in other neighborhoods.

Use federal dollars to build single-family homes and city resources to develop mixed-income housing.

To correct the imbalance, the group also wants the city to collaborate with suburban neighborhoods and cities to make room for more affordable housing in wealthier, white areas. Low-income residents in racially-segregated areas would have priority in renting these units.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Residents accuse Cincinnati of discriminatory housing over decades