Stuck in licensing limbo, Florida nursing students want answers. They’re not getting them

He graduated from a nursing program in South Florida and passed a national exam but Jasiel Vilarino’s hope of working as a nurse has turned into a frustrating yearlong ordeal.

Like dozens of other students in a region with an acute nursing shortage, he’s been left in limbo awaiting a critical nursing license or at least clear answers from health bureaucracies in two states. The delay cost him a job at Mercy Hospital and he’s been forced to work as a part-time DJ while struggling to manage $50,000 in student loans.

“It’s been a year like this, fighting back and forth,” Vilarino said.

A Herald investigation in January found that the careers of Vilarino, and hundreds of other aspiring nurses, have been put on indefinite hold over a standoff between Florida, where they trained, and New York, which administered the online tests but has refused to issue licenses because of questions about the checkered records and accreditation of some for-profit nursing schools in South Florida.

Now, the Herald has found, a work-around process intended to allow Florida to issue licenses based on the New York test scores has also been the subject of complaints, with students reporting confusing information and long delays. Vilarino, after nearly a year, finally got his official passing score transferred last week. Now, he’s waiting on Florida to take action.

THE WAITING GAME

Vilarino is in a group chat of over 100 similarly situated people. Among them is Danys Rivera, 37, who graduated from Future Tech Institute in 2021, a Miami for-profit school that is now closed.

She passed the national nursing exam, known as the NCLEX, through the New York online portal in July 2023 and waited seven months to receive her license with no results. So, she retook the exam — this time, using Florida’s portal.

New York is a popular option, especially for test takers for whom English is not their first language. It offers unlimited chances to pass. Florida only offers three. Either way, a New York license would have allowed her to practice in Florida because of the Florida Board of Nursing’s licensure by endorsement process.

While Florida enforces a three-tries-and-you’re out, policy, an applicant can earn another chance at the test by successfully completing a Florida Board of Nursing approved remedial course.

Unlike Vilarino, Rivera was able to keep her position at QPS Miami Research Center while she waited for her license. Still, even though Florida eventually issued her license, retaking the exam took an emotional and financial toll. Between application fees and test preparation, she spent upwards of $500. After working an eight-hour shift as a medical assistant, she came home and studied for hours at night. It was an exhausting experience, which only adds to her frustration over the uncertainty now surrounding her license.

They took my money,” she said. “They took my time.”

Adding to the stress, she said, is the lack of information from the New York State Education Department. According to Rivera, the department never sent her any written communication explaining the reason for the delay.

Lack of oversight

These students and dozens of others have been swept in the questions now surrounding South Florida’s for-profit nursing school industry, where some outlets have been hit with charges of rampant fraud. In one recent example, three South Florida men were tried for allegedly running a nursing-school “diploma mill.” According to prosecutors, over 3,500 students paid between $10,000 and $20,000 for fake academic credentials from the now-defunct Palm Beach School of Nursing. The three were found guilty in December.

State Rep. Anna Eskamani, an Orlando Democrat, told the Herald that there needs to be more accountability and oversight of for-profit institutions, which she says are often marketed towards communities of color and low economic means.

“They try to market themselves as something you can go through quickly and have a job right away so you can pay back whatever loans you have and essentially scale up and find economic mobility,” she said.

Though not every school was issuing bogus credentials, the scandals and lack of oversight from Florida health regulators, has put many aspiring nurses under additional scrutiny. They spent years pursuing nursing degrees, shelled out thousands of dollars for training, and passed the key test to become a nurse.

But rather than finding themselves in better-paying careers, they’ve been left with big bills and uncertain futures in a healthcare industry with a growing need for nurses.

“I feel stuck in my life because I see people moving forward,” Vilarino said. “I feel like I went to school for a year for nothing.”

Dashed dreams

A Miami native, Vilarino’s longtime dream of becoming a nurse nearly came to fruition when Mercy Hospital accepted him into a residency program for recent grads. The training program afforded Vilarino, now 31, four months to secure his license while he learned hospital procedures and protocol.

Six weeks after passing his exam, those dreams were dashed when he couldn’t produce his license because the New York State Education Department was investigating his school, the now defunct Sweetwater-based for-profit Universal Career School. The New York investigation could take a year or two, a customer service representative told him.

He spent the next eight months going back and forth with the department. Since they would not issue his license, he pleaded with them to at least release his passing score so he could seek his license from Florida. They refused.

“I was going crazy because at this point in my life I didn’t know what to do. I lost my job,” he says.

He considered working in a restaurant but eventually found work as a part-time DJ.

Vilarino decided to retake the exam in Florida but changed his mind when a member of his group chat, Romelia Farinas, informed the group that, after 10 months of back and forth, the New York State Education Department agreed to send her score to Florida.

When asked how long this score transfer process had been an option, the department would not say but told the Herald that this is not a “typical certification request” and provided the following statement: “A handful of applicants have requested to have NCLEX scores certified in Florida and we have processed those requests.”

Vilarino, and several others who spoke to the Herald, said the department never informed them that transferring the score to Florida was an option and that they only found out by word of mouth.

Both Vilarino and Farinas graduated from Universal Career School in 2021 and 2022, respectively.

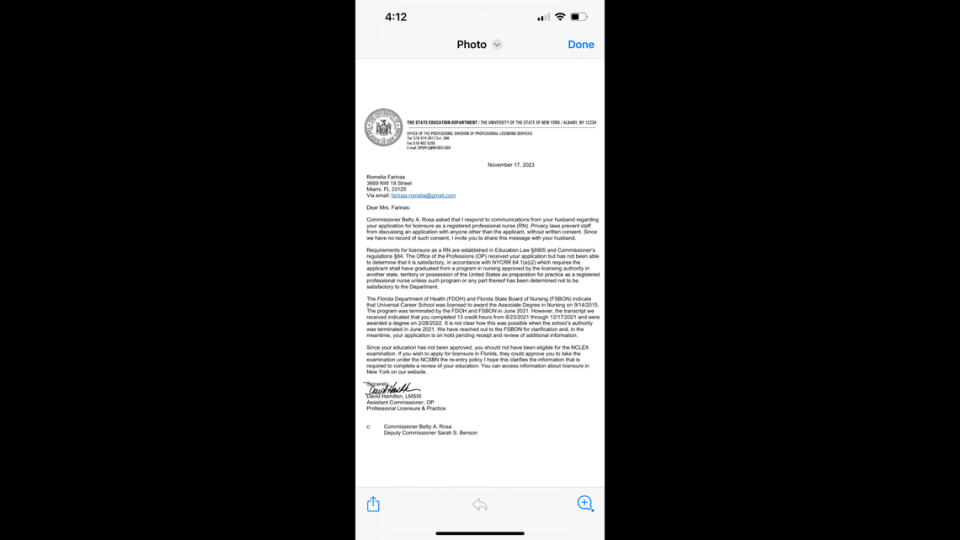

The Herald obtained a letter that the New York State Education Department sent Farinas saying that the Florida Department of Health and Florida State Board of Nursing terminated her school’s nursing program in June 2021. It noted that her transcripts indicated that she completed coursework at the supposedly terminated program in the fall of 2021 and graduated on Feb. 28, 2022.

“Since your education has not been approved, you should not have been eligible for the NCLEX examination,” the letter read.

Eligible or not, Farinas passed on her second try.

No straight answers

Another graduate of the shuttered Universal Career School is Vilarino’s cousin, Miguel Menendez, 30, who studied medicine in Cuba before moving to Miami 10 years ago.

While both cousins struggled the last year to get their licenses, Menendez feels guilty about encouraging his cousin to attend the closed nursing program —particularly since he, unlike Vilarino, was able to find work in the healthcare field, working as a behavioral therapist while he waits for his nursing license.

Still, the delay cost him time and money as he struggled to support his growing family. His wife was pregnant during most of this ordeal.

“They stopped me for a year with no license, no getting paid, no continuing my education,” he said.

He submitted the application to have his score transferred to Florida and is still waiting for his license.

The students also have struggled to get clear answers about the process of license review from health departments in both states.

Vilarino and others say New York State Education Department representatives have often been dismissive and provided contradicting information. According to Vilarino, one week, an employee told him that they sent his score the previous day. The next week, a different employee said they were not sending his score because of an accreditation issue with his school.

His cousin, Menendez, said he experienced similar frustration dealing both New York and Florida, with Florida employees changing their story on whether or not they received his score from New York.

Even students who have managed to cut through the red tape and confusion to secure their licenses, described the overall experience as dehumanizing.

“I felt like I was living in Cuba where I used to live with no rights like I wasn’t a human being,” Menendez said.

This story was produced with financial support from the Esserman Family Foundation in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners. The Miami Herald maintains full editorial control of this work.