Pacific gray whale numbers increase by 33%, showing rebound after historically low counts

The number of eastern north Pacific gray whales increased an estimated 33% compared to a year ago, offering continued evidence the gigantic mammals are recovering from what biologists termed a “unusual mortality event.”

Famous in Oregon because of their migrations along the coast each winter and spring, the number of gray whales was estimated at 19,260 for 2023-24 in numbers released Thursday by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

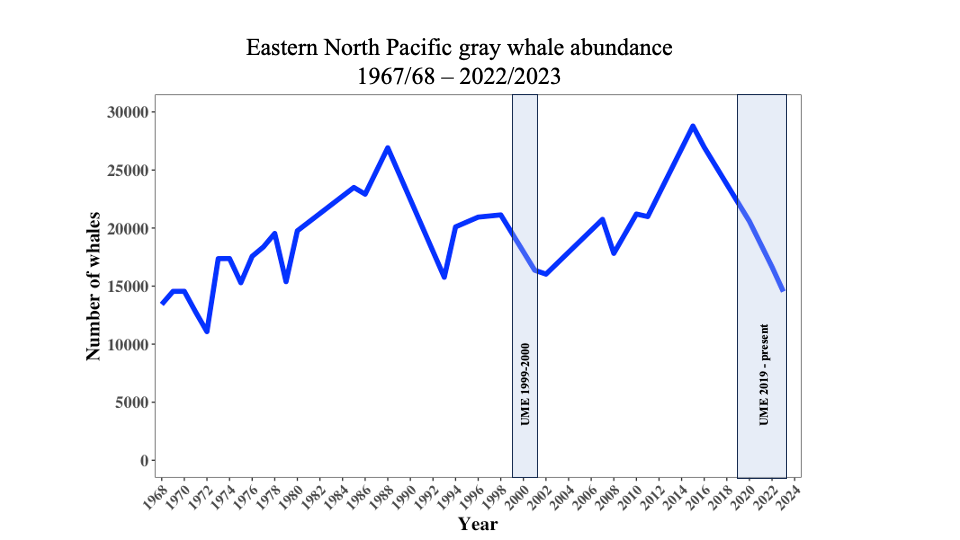

That’s up from 14,530 in 2022-23, the lowest number since counts began in the 1960s, and 17,430 in 2021-22.

The number of calves also rebounded, with 412 counted in 2023, up from a historically low 217 in 2022.

“The latest counts indicate that the gray whale population has likely turned the corner and is beginning to recover,” said Michael Milstein, public affairs officer with NOAA Fisheries. “It’s a perfect time for people to see them as they swim north with new calves to feed.”

Milstein was referencing the beginning of whale watching week on the Oregon Coast, which lasts from Saturday through Sunday, March 31. Trained volunteers will be stationed at 15 sites along the coast to help visitors spot whales and their calves while answering questions from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. each day.

Data for the population estimates comes from counts at multiple locations combined with modeling developed over decades of taking the counts.

How low have gray whale numbers dropped?

Over the past five years there has been real reason to worry about the future of gray whales.

After recording an all-time high of 28,800 whales in 2015-16, numbers plummeted sharply over the next half decade, reaching the lowest number since counts began in the late 1960s.

The low numbers came during what biologists termed an “unusual mortality event,” which included high numbers of dead whales washing up on Pacific shores and high numbers of thin and undernourished animals.

Evidence of the mortality event hit home in Oregon when two dead gray whales — and four whales overall — washed ashore at frequently traveled locations on the Oregon Coast.

It's believed that ecosystem changes and a declining quality of prey in the northern Bering and Chukchi seas caused the decline.

“This malnutrition led to increased mortality during the whales’ annual migrations and decreased production of calves," NOAA said. "This resulted in an overall decline in population abundance.”

Climate change in the Arctic appears to have contributed to the poor nutritional status of the whales in recent migrations, but “it is not clear whether long-term climate change played a role. Gray whales have experienced similar declines before but their numbers fully recovered,” NOAA said.

Indeed, gray whale numbers have dropped as low as 15,000 in 1978-79 and 1992-93, and 16,000 in the early 2000s and each time they’ve rebounded.

Evidence of a rebound

In addition to the rebound in the population estimates, the number of dead whales washing ashore has decreased, as has the number of malnourished whales, officials said.

A group of scientists recently decided the factors contributing to the "unusual mortality event" no longer apply. In fact, the group determined the end of the mortality event was actually around November 2023.

It was the second mortality event declared since 2000. The first mortality event took place from 1999-2000 when their numbers dropped to 16,000.

“We know that gray whales have recovered from previous declines,” Milstein said. “The question now is whether the playing field has changed because of climate change such that they will have a more difficult time recovering than we have seen in the past.”

Could rise and falls just be whales reaching carrying capacity?

Whale experts have speculated the rise and fall of gray whale numbers over the years may just be the species hitting its natural carrying capacity.

"There was some talk at the beginning of the (mortality event) that the population had hit carrying capacity and was simply going through a natural readjustment — where the numbers balance out with the food or other environmental factors they need." Milstein said. "It seems like a big deal to us, but for them it may simply be the kind of thing that happens every so often. Certainly this is a good sign, but we will keep watching because the population still has more room to recover."

Zach Urness has been an outdoors reporter in Oregon for 15 years and is host of the Explore Oregon Podcast. Urness is the author of “Best Hikes with Kids: Oregon” and “Hiking Southern Oregon.” He can be reached at zurness@StatesmanJournal.com or (503) 399-6801. Find him on Twitter at @ZachsORoutdoors.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Pacific gray whale numbers increase by 33% since 2023