'Like a magic carpet.' New creature seen by Cape resident off Costa Rica now has his name

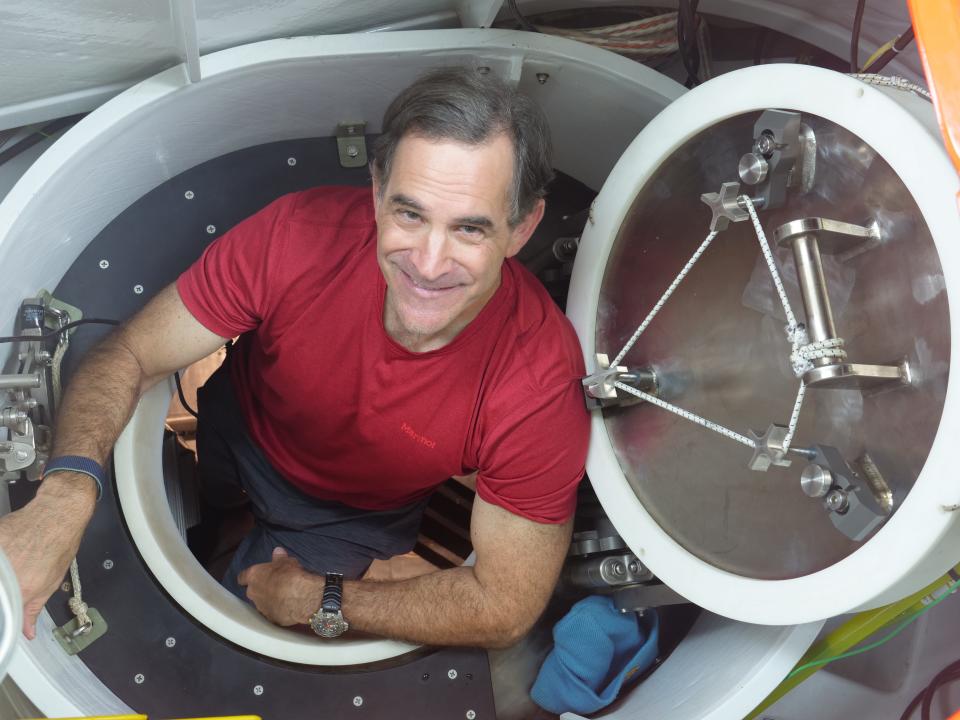

As the lead pilot for the deep-sea submersible Alvin, Falmouth resident Bruce Strickrott already has a claim to fame. He's one of just 45 people who've driven the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution-operated vehicle since it launched in 1964.

Now the 28-year Alvin veteran has the added distinction of having a new species of deep-sea worms named after him. Called Pectinereis strickrotti, the worms were first spotted in 2009 and again in 2018 near a methane seep in the Pacific Ocean about 30 miles off Costa Rica. They were finally confirmed and announced as a new species in a study published in the science research journal PLOS ONE on March 6.

Strickrott was literally the driver behind the discovery, shuttling researchers more than half a mile to the sea floor to study the marine life around the seep, an area where methane escapes the seafloor in the form of gas bubbles. He was one of the first, along with California-based marine biologist and study leader Greg Rouse, to get a fleeting glance at the worms during the 2009 dive about 3,280 feet below the surface.

Rouse, of UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, gave Strickrott's name to the new species in recognition of his role in its discovery.

"I'm honored that Greg saw fit to name this after me. It means a lot," said Strickrott, speaking recently by phone from the mid-Pacific at another study site along the East Pacific Rise, just north of the equator. "I think it's representative of how the program and the technology helps scientists get to places they wouldn't be able to go without Alvin."

A first encounter with the sea worm

He recalled the first encounter with the newest sea worm species, in 2009, when he and Rouse spotted two of the worms during a dive.

"We didn't know what they were. We just saw these creatures sort of hovering about six feet off the bottom. They were long and skinny," he said.

The worms were difficult to see and Strickrott said he tried to nudge Alvin in for a closer look. But, as he humorously says, "it's hard to creep in a submarine," and so off the worms went.

The researchers, whose work was supported by the National Science Foundation, saw enough to suspect they might have witnessed something new to science.

It wasn't until 2018, when the researchers returned to Costa Rica's methane seeps, with Strickrott once again at the helm of the U.S. Navy-owned submersible, that they again encountered the creatures. This time they saw several individual worms.

"They were not nearly as skittish as the first time," he said, explaining they were likely in reproductive mode.

'Move like a magic carpet'

As they did the first time, Strickrott said the worms' graceful way of moving struck him as unique. He'd seen other sea worms move in a twisting motion, "almost like a helix." In contrast, Strickrott's worms undulate.

"These really move like a magic carpet," he said.

During that dive, Strickrott became the first to capture live specimens for closer study, using a five-chambered vacuum canister device on Alvin known as the “slurp gun." It can be a delicate operation that requires some skillful maneuvering.

"We work with some really complex equipment. And it's a 23-foot submarine that you're pirouetting around in," he said. "There are times when it's frustrating. Getting these really fine samples doesn't always go the way you want."

The team also captured images and video of the worms, evidence they used in proving them to be members of a previously undiscovered species — a process that can take years of anatomical and DNA analysis, and comparing to known species.

A 4-inch long member of the ragworm family

Strickrott's worm is a 4-inch long member of the ragworm family, a group of about 500 species of segmented, mostly marine worms that look like a cross between a centipede and an earthworm. They have elongated bodies with rows of bristled appendages called parapodia on their sides and a hidden set of pincer-shaped jaws that can be extended for feeding.

It's not the first time a new species has been named for a pilot of Alvin, which will officially mark six decades of discovery this June. Past pilot Dudley Foster had a new comb jelly named for him, Bathocyroe fosteri, in the late 1970s, and Paul Tibbetts helped collect a new species of Pacific mussel in the late 1980s, resulting in the naming of Punctabyssia tibbettsi.

The worm is not the first new species to bear Strickrott's name. In 2007, another new species discovered in the southern part of the East Pacific Rise was named Eptatretus strickrotti.

"If you go to Wikipedia you'll find Strickrott's hagfish, which is basically an animal that eats dead fish," he said, adding, "the last part of my name is rot, so it works for me."

With the ragworm, Strickrott said, he now has "one that's an invertebrate and one that's a vertebrate."

At the Costa Rican methane seeps

According to WHOI, Rouse and other researchers have observed about 450 species at the Costa Rican methane seeps since 2009, with Strickrott's ragworm bringing the number of species that were new to science to 48. Rouse said these stats underscore how much more there is left to learn about the inhospitable, deep-sea ecosystems and their biological importance.

“We’ve spent years trying to name and describe the biodiversity of the deep sea,” he said. “At this point we have found more new species than we have time to name and describe. It just shows how much undiscovered biodiversity is out there.”

Strickrott said it's inspiring to be a part of the discoveries.

"The life down there is teeming. It's just mind-blowing. It's proven that life is persistent. If there's energy, if there's resources, it's going to take advantage," he said. "It's a pretty special experience to go down there, and to go down with experts. I'm an engineer, yet I'm getting trained by the best by being there and talking to them. It's a joy to be part of it."

Besides Rouse, other contributors to the Strickrott's ragworm study include Sonja Huč, Avery Hiley, and Ekin Tilic, all of Scripps. Tulio Villalobos-Guerrero of the Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada is the study’s first author and conducted the primary anatomical analysis.

Heather McCarron can be reached at hmccarron@capecodonline.com, or follow her on X @HMcCarron_CCT

Thanks to our subscribers, who help make this coverage possible. If you are not a subscriber, please consider supporting quality local journalism with a Cape Cod Times subscription. Here are our subscription plans.

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: Deep-sea worm named for Alvin pilot Bruce Strickrott of Falmouth