When Kansas police kill people, the public often can’t see bodycam footage. Here’s why

Editor's note: Viewing this story in our app? Click here for a better experience on our website.

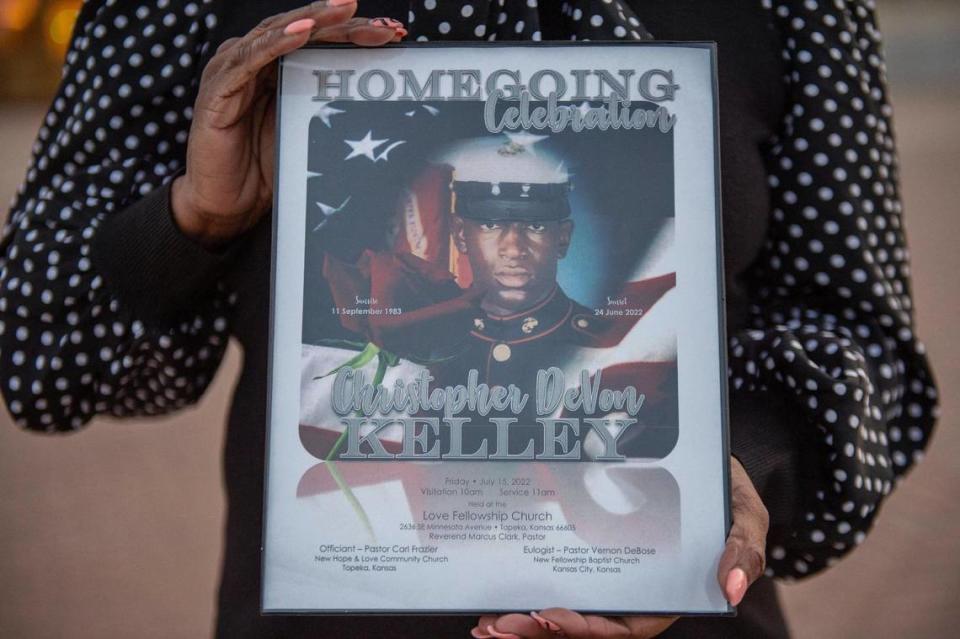

Christian Kelley has a question for Topeka police: What are you hiding?

Her brother Christopher Kelley was in the midst of a mental health crisis when Topeka Police Department officers shot and killed him in June 2022.

Though a family representative viewed the body camera video, the city has not publicly released the recordings.

“If you state that something went a certain way, then there should be no problem releasing the tape to the public,” Christian Kelley said.

But in Kansas, just because body cameras are widely used doesn’t mean the public gets to see that footage.

Body camera recordings are considered criminal investigation records. Under Kansas law, that classification gives police departments or other public officials like district attorneys broad discretion in deciding whether the recordings get released or stay shielded from public view, even after a case is closed. According to an analysis by The Star, that discretion has created a muddled patchwork of transparency — or in many cases, a lack of it — when it comes to body camera footage across the state.

In the five years from 2019 to 2023, police officers fatally shot 47 people in Kansas. Officers were cleared of criminal charges in all of the cases. The Star requested videos from all of the shootings under the Kansas Open Records Act.

Where recordings existed, officials denied releasing them to the public 67% of the time. Agencies cited a number of reasons. In Christopher Kelley’s case, Topeka officials said the footage was “not in the public’s interest.” City Attorney Amanda Stanley also wrote in her denial letter that the video was “disturbing” and that its release would be “a clearly unwarranted invasion of the personal privacy of the officers.”

In a denial letter regarding another fatal shooting by Topeka police in 2022, Stanley wrote, “This Officer has been through enough.”

Videos that officials released from other cities across Kansas varied: Some were heavily blurred, while others edited out either the beginning of the interaction or what transpired in the immediate aftermath of a shooting. Two agencies declined to release recordings, but allowed a reporter to watch the videos in their offices.

Experts and advocates say transparency is critical — particularly when someone dies — to the relationship between police and the communities they serve. When introduced, body cameras were pitched as a tool to enhance transparency.

“When you limit the public’s access to what public officials do, police officers and law enforcement, I think you diminish the public trust in these institutions,” said attorney Tom Porto.

If Christopher Kelley had been killed by police in Missouri, the investigation file, including footage, would become an open record once the case is closed. But that’s not the way the law works in Kansas.

In Porto’s words: “The statutes in Kansas do more to limit trust than ensure it.”

Marine Corps veteran

Christopher Kelley was born in Kansas City and moved to Topeka around age 5 when he was adopted along with his sister and a niece.

He was curious, kind and “a very, very vibrant little boy” with chubby cheeks like a chipmunk, Christian Kelley said.

As a teenager, he became a cheerleader, ran cross country and was active in his church.

After graduating from high school, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps and the U.S. Army, serving in Operation Enduring Freedom. While he was in Iraq, he signed up for a mission but a friend ended up going in his place, Christian Kelley said, and his friend was killed.

“That traumatized him quite a bit,” she said. “The joy he normally had was lost.”

When Christopher Kelley returned home, his family noticed changes. He was closed off, shut down. They urged him to seek help at the Veterans Affairs Hospital. He was hesitant, unsure if the mental health services there were a good fit for him, his sister said.

He got a job at a nursing home where he was a cook. Christian Kelley said he was a great chef who could make “a mean pot of oxtails.” And he was a dedicated father who stressed the importance of getting a good education to his four children, now ranging in age from 4 to 18.

On June 24, 2022, Topeka police were called to 4th and Holliday streets, near railroad property. Prosecutors alleged Christopher Kelley threatened a railroad employee with a knife. Officers negotiated with him for about an hour and deployed bean bag rounds and rubber bullets, weapons police deem “less lethal” and are not intended to kill someone.

“Those methods had no impact on Kelley and he continued to disobey commands and on occasion continued inflicting injuries to himself with the knife,” the Shawnee County District Attorney’s Office wrote in a news release.

Then he “charged at officers with the knife extended over his head,” the DA’s office said.

Multiple officers fired, killing the 38-year-old.

LaRonna Lassiter Saunders, a family representative for the Kelleys who is also an attorney, viewed the footage. She thinks officers escalated the situation and that the department should release the recording.

“You’re serving the public and there’s a shooting or killing, there’s a taking of someone’s life. You don’t get privacy on that. You need to be very transparent at that point,” Saunders said.

Family members by state law are allowed to view body camera footage. Most of Kelley’s family opted not to watch it.

“We did not want to experience that type of trauma,” Christian Kelley said.

But she still thinks the public should be able to see it, especially since taxpayers usually foot the bill for equipment like body cameras.

“Can we see our return on investment?” Christian Kelley said.

“A need for transparency is appropriate.”

Footage and findings

The Star submitted more than 50 requests for footage to 28 law enforcement agencies — some shootings involved multiple departments, and some departments had multiple shootings. Five shootings did not have footage at all. Agencies denied public release for 32, or two-thirds of the existing recordings.

In two of those cases, a reporter viewed footage with the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks in Topeka and the Cowley County Sheriff’s Office in south central Kansas.

Footage from KDWP had not been viewed by the media previously, according to current staff at the agency. Officers from four departments including KDWP responded in March 2021 to a welfare check where they found a man standing outside a car near the border between Clark and Meade counties, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation said.

Within two seconds of the eight-minute recording, a barrage of gunfire begins and the man falls to the ground. It’s unclear why existing footage from the preceding interaction was not included in what the agency showed.

Officers killed Jim Wright, 67, of Fowler, Kansas. Authorities said he was armed.

The reporter also viewed recordings at the Cowley County Sheriff’s Office in Winfield. In April 2022, three deputies confronted a woman who was stopped on a rural road. Footage from the three deputies indicated she did not know what state she was in.

The recording showed the interaction escalated and she reached her right hand toward the center console of the Jeep. As a deputy shocked her with a Taser, she began firing a gun. All three deputies were struck and returned fire.

The deputies killed Andrea Barrow, 32, of Arkansas City, Kansas. They found her in possession of a stolen license plate.

Undersheriff Christina McDonald said the sheriff’s office was fine with providing the videos for viewing at the office, but that it also wanted to protect the public, the deputies and their families, and Barrow’s family.

McDonald said it was a delicate line and they “walk that as well as possible.”

The officers were cleared in both homicides.

The Star obtained videos in 11 other police shootings, including fatal encounters in Baxter Springs, Chanute, Goddard, Ness County, Olathe, Sedgwick County, Wellington and Wichita. Some raised questions about the justification for the shootings, if policies were followed and if statements made by officials were accurate.

Over five hours of footage showed negotiations in a standoff after someone reported a domestic disturbance in March 2022 at a trailer home in Baxter Springs. Joplin, Missouri, police responded to assist the local department, and one of their snipers fired into the trailer, striking and killing 2-year-old Clessie Lynn Jane Crawford.

In August 2023, Ness County Sheriff’s Office deputies pleaded with Jesse Nicholls, 46, outside a home where someone had reported a domestic disturbance.

During a 66-minute video, one of the deputies said, “Think about me and everybody else cause you know how this ends and you know how bad that’s going to mess me up. I’m begging with you, man.”

“It doesn’t matter anymore,” Nicholls replied.

Nicholls fired into the ground and a deputy shot him.

County Attorney Jacob Gayer characterized the encounter differently. In a news release, he wrote, “The subject charged towards Deputies before discharging, towards officers, a single round.”

Gayer declined on March 12 to comment when asked about the wording he used.

Videos from four other fatal shootings had been previously publicized.

The Star also requested the body-worn camera policies from 28 agencies. The policies varied from two to 12 pages. Chetopa, a small town in southeast Kansas, said they were in the process of implementing a policy.

Only policies from Topeka and Chanute make no mention of how requests for disclosure are to be handled. City of Topeka spokeswoman Rosie Nichols said there was “no reason” for that to be included in a policy on how body cameras are used by officers. However, a December report from the Police Executive Research Forum, a policing think tank that recommends best practices, said “every agency should have a clear (body worn camera) release policy.”

Agencies that included information about body camera disclosure requests were fairly similar, citing the Kansas Open Records Act or referring the decision to police chiefs.

Videos kept from public

The public may never know exactly what happened to Christopher Kelley. Or 25-year-old Amaree’ya Henderson in Kansas City, Kansas. Or Nicole Dechant, 29, in western Kansas. They are among 26 fatal police shootings where agencies denied public release of the footage.

Nichols, Topeka’s spokeswoman, said the city manager coordinates the review of body camera requests. Interim City Manager Richard Nienstedt was “not available for an interview on this topic.”

She went on to say that “these types of KORA requests are carefully considered” and that several factors are weighed when footage is requested. That includes whether a criminal case is still open, if footage reveals confidential sources and if it’s in the public interest, among others.

“Video recordings often show an individual’s (including victims, alleged offenders, witnesses or officers) worst day in extraordinary detail,” Nichols said. “As such, the city holds requests for these records to the highest scrutiny and protection.”

According to the Fraternal Order of Police contract with Topeka, the city manager can release footage to the public “after communication with the officer(s) whose actions appear in the video.”

Eight people have died in fatal police shootings in Kansas City, Kansas, in the past five years. The department released one video in 2022. It showed a struggle between officers and Lionel Womack, a former police officer who was killed in the encounter. Kansas City, Kansas Police Department Chief Karl Oakman said “it was that specific case” that led to the video’s release.

The department recently denied releasing footage from the other seven fatal shootings.

“If it’s something that we feel is in the best interest of the public, then we would release it,” Oakman said.

Von Kliem, director of the consulting division for Force Science, which consults and trains police, said if the average citizen was asked to review a shooting case, they would likely say they are not qualified. Releasing videos, Kliem said, is asking the public to do just that in the name of transparency.

He said the public needs to be educated on the legalities of using force and how watching footage differs from what the officer was experiencing and perceiving during the encounter.

The decision to release videos should be made on a case-by-case basis, Kliem said, depending on the status of the investigation, the political climate and whether the shooting was a “close call.” In those instances, Kliem would want to know if the public was ready to view it in “a non-bias way.”

“Clearly the answer’s no in most cases,” he said.

‘Right to know’

Agencies need to be open to public scrutiny, said Lora McDonald, executive director of the social justice organization MORE2. And in some cases, footage would show an officer’s actions were justified.

“Let the public have the discourse,” she said. “But you’re basically saying, ‘The public can’t be involved, we know what we’re doing and everything’s fine.’ But you work for us.”

Christopher Bush, a criminal justice professor at Allen County Community College who has researched the impact of releasing body camera recordings, said a 67% denial rate for recordings was high.

The longer disclosure takes, he said, the more suspicious people get. And that can drive a wedge between police and the community.

Some Kansas agencies make a point of releasing footage for this reason. Johnson County District Attorney Steve Howe generally releases clips from body camera footage when he announces charging decisions.

In a statement, his office said doing so helps explain “my decisions on officer involved shootings.”

“This transparency helps maintain the public’s trust in the criminal justice system and the decisions made,” Howe said. “It also requires us to balance transparency with the privacy rights of all individuals involved. We also must be mindful of the graphic nature of some of the content. That is why we redact or pixelate portions of some videos.”

Recordings from four of the five last fatal police shootings in Johnson County have been released. Footage from an August 2023 shooting has not yet been released. Fairway Police Department Officer Jonah Oswald and suspect Shannon Wayne Marshall were killed in the encounter at a QuikTrip in Mission. Prosecution of another suspect, Andrea Cothran, remains ongoing.

Even when footage is released, it can provoke additional questions.

Howe released some clips from the 2018 shooting of 17-year-old John Albers in Overland Park. But it took years and multiple lawsuits, including one filed by The Star, to get a more complete picture of what happened. In 2021, the city released additional videos and reports.

Evidence concluded that each of the bullets fired at the teen entered through the side of the minivan, answering some questions about the officer’s positioning and whether he was in the vehicle’s path.

Sheila Albers, John Albers’ mom, said releasing footage won’t solve everything, but disclosure is a valuable step.

“The reason why footage is important, and it’s not just John’s case, this is nationally, is that it then prevents false narratives from being put out to the public,” she said. “The person or the entity that controls the footage controls the story. And if we don’t have disclosure of footage, then the governmental entity can tell whatever story they want.”

Trust is built through accountability and transparency, said Micah Kubic, executive director of the ACLU of Kansas.

“The public absolutely has the right to know what happened, has the right to know whether police officers acted in a manner that is consistent with their training, that is consistent with the law, that is consistent with good common sense,” he said.

Future of footage

A measure in 2018 proposed public access to body camera footage in Kansas. But that language was stripped from the bill. The law that passed “was watered down,” said Sen. David Haley, a Kansas City, Kansas, Democrat.

Haley said he supports the release of footage when someone dies as long as its release would not interfere with an investigation. He also said there “should be continuity” across the state. He compared Johnson County’s decision to release recordings with Wyandotte County’s denials, which he called “unacceptable.”

Rep. John Resman, an Olathe Republican who was in law enforcement for 28 years, said “a patchwork of other laws” already exists.

In terms of disclosure, he said other information in criminal cases is not released.

“So I think it should be up to the DA’s office or the district attorney to decide what’s going to be released or when,” he said of body camera recordings.

In fatal police shootings where there is no prosecution, Resman said he generally supports the release of videos.

No body camera legislation is on the table this year in Kansas.

In California, agencies must release footage in critical incidents within 45 days. Footage may be released in other states like Ohio, which provides an exemption in its open records law when someone is killed by police.

Cities can also pass their own ordinances, or individual police departments can implement disclosure policies. Agencies from Seattle to New Orleans and Baltimore may release footage within two to nine days, according to the Police Executive Research Forum.

Max Kautsch, an attorney who focuses on open government law, said he thinks it’s more likely change will come from the courts. In 1987, the Kansas Supreme Court affirmed records in a Johnson County triple homicide could be withheld because their release was not in the public interest, which must go beyond curiosity. Kautsch said that has created “an accountability disaster.”

But more recent decisions, including in the Albers case, have emphasized what public interest means. In 2021, The Wichita Eagle won a years-long court battle for body camera recordings in two separate incidents.

“This is a matter of public interest because the community at large has an expectation that police investigations will be conducted fairly and appropriately, especially when a police officer is implicated,” Sedgwick County District Court Judge Jeffrey Goering wrote in the decision.

In cases of potential misconduct or police shootings, Kautsch said, “there’s an expectation by the community at large that the law enforcement agency acted reasonably in taking the action that it took, and the only way to challenge or verify whether the conduct by law enforcement was reasonable is disclosure of the records.”

Christian Kelley said she does not think the City of Topeka has met the public’s expectations when it comes to transparency.

The sudden loss of Christopher Kelley has been difficult for her, his children and other loved ones.

But she said she hopes something good can come from her brother’s death. She wants city officials or state lawmakers to change the disclosure laws.

“There’s an opportunity here,” she said. “I wish they would take it.”