How green is biomass in Georgia? Enviva’s bankruptcy highlights cracks in the industry

If a tree is grown as a commodity with the sole purpose of eventually being cut down and then processed for energy, or biofuel, it should be renewable by most environmental standards.

The Georgia Forestry Commission certainly thinks so. But environmental lawyers and activists say no.

The relatively young energy biofuel or biomass industry – only about 15-20 years old – reigns in the southern U.S., thanks to an ample amount of commercial timberland. Georgia alone has 24 million acres, more than any other state in the country.

And with the recent declaration of bankruptcy by Envia, the world’s largest biomass producer, lawyers and activists see this as an inflection point for the industry. With Georgia at the center of the industry, the legal action has brought the industry to the forefront of the climate change discussion.

Chief among those supporters of the industry is the Georgia Forestry Commission. One of its spokesmen explained its reasoning.

Devon Dartnell, Director of Forest Services and Marketing at the Georgia Forestry Commission, said 91% of the timberland in Georgia is privately owned.

“The entire state is 36 million acres, so two-thirds of the state is forested. We’re in a pretty good place from a sustainability standpoint. We grow more wood every year than we harvest by 50%,” he said.

Dartnell added that 7.1 million of the 24 million acres are owned by families and they depend on the timber industry for their livelihood. Plus, it is a massive economic engine for Georgia.

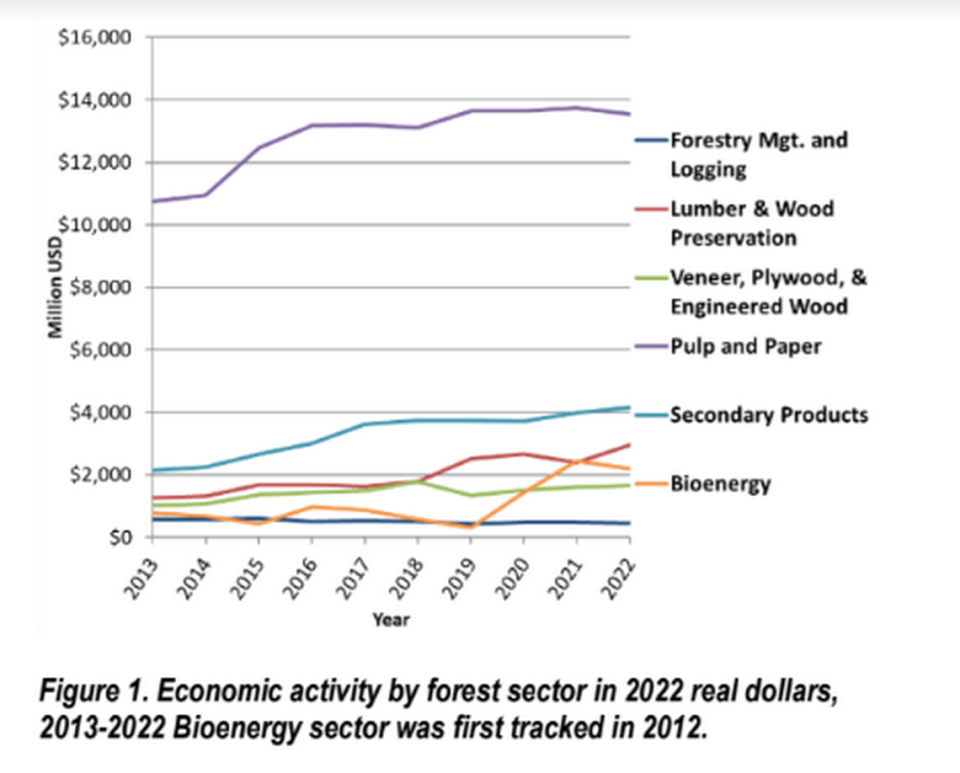

“Georgia is number one in the nation for annual economic impact from forestry, from 42 billion in 2022,” Dartnell said. “Eleven paper mills and one wood pellet mill (which is owned by Enviva) are 12 of the biggest buyers of Georgia’s market.”

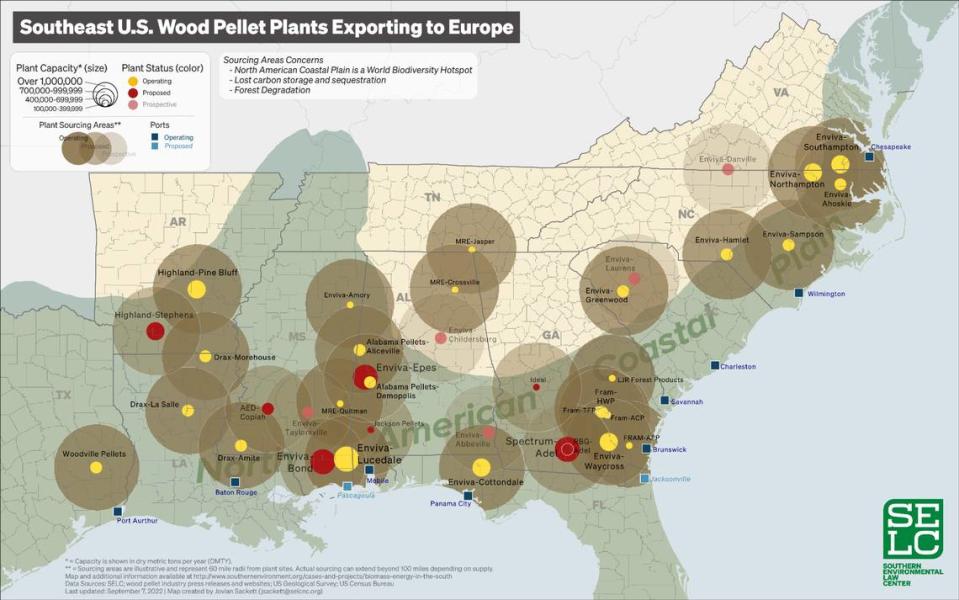

When a thinned tree is delivered to Enviva’s biomass plant in Waycross, Georgia, there are several polluting steps that go into the process to go from a tree into tiny wood pellets that are eventually shipped to Europe for fuel.

First there is debarking, followed by chipping, hammer milled which dries the moisture out of the wood, then it enters the pellet mill, then it is cooled down, put on a train to Savannah, and shipped to the Netherlands and the U.K. where it is burned as a “renewable” resource.

Environmental lawyers and activists have criticized the forestry biomass industry as not renewable and not “carbon neutral,” saying it is more harmful to climate action and pollutes communities where the is timber is manufactured and processed.

Last month, Enviva, a biomass giant that creates wood pellets for fuel in Europe, filed for bankruptcy, declaring $2.6 billion in debt. Lawyers at the Southern Environmental Law Center and activists at Georgia Interfaith Power and Light signal this as a pivotal moment

for a failing industry on multiple fronts.

The company employs 1,000 people and has corporate offices in England, Germany, and Japan, with 10 plants operating throughout the Southeast. Its annual revenue hovers at $1.1 billion.

Young trees don’t sequester as much carbon as older trees, and the types of trees Enviva and other biomass plants like to use are typically in the 30 to 40-year range.

“Thinned trees from a pine plantation can’t recapture the carbon that is polluted from burning,” Heather Hillaker, a senior attorney at the SELC, said. “It’s important to think about where we are, we have like five years to drastically reduce CO2 emissions” (Hilaker is referring to the irreversible damage caused by warming levels if the world passes at 2 degree Celsius threshold by 2030).

Othelllious Cato, an organizer for GIPL in Southern Georgia, works with green teams at churches in marginalized communities like Lumber City, Hazlehurst, and Adel. His primary concern is educating people on the importance of reclassifying burning biomass as not carbon neutral and how much the manufacturing plants harm communities.

“It’s never been carbon neutral,” Cato said. “Burning of wood pellets for power emits more carbon per megawatt produced than burning coal.”

The entire process adds greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

“You have a loss of soil carbon, gases during harvesting, transportation to the plant, then the emissions at the plant, then shipped to Europe or Asia,” Hillaker said. “Even if you ignore the CO2 aspects, the plants emit harmful air pollutants, hazardous air pollutants like methanol, formaldehyde, and acrolein. When you manufacture wood pellets you are releasing volatile organic compounds and natural air pollutants.”

Waycross produces the 800,000 dry metric tons per year. They started operations just three years ago.

Jason Rubenbauer, president and CEO of Waycross-Ware County Development Authority, said Enviva is “extremely important to the community. They currently employ 100 people and are heavily engaged in the community.”

The Ledger-Enquirer asked about issues with dust and pollution. Rubenbauer dismissed those claims:

“Pollution is not an issue from what I see, I hear a lot of chatter about the pollution,” he said.

However, SELC found Waycross violated its air quality permit in November 2021.

“Georgia Environmental Protection Division has acknowledged that they are in violation, but Enviva want’s to modify the permits”

Cato said a specific study needs to be conducted in Waycross and plans to reach out to the Development Authority to get this started.

“We want to reach out and partner and see direct, concrete, evidence, of these health concerns,” Cato said. “The industry is continuing to grow in poor, rural communities, and health risk is going to be a problem.”

A study from 2018 found that wood pellet production facilities in environmental justice communities are 75% more likely to happen in areas below poverty and non-white communities.

Pellet mills get a local tax break to operate, which Hillaker and Cato both suggest is problematic.

“The companies get crazy tax breaks and are not directly contributing to the community,” Cato said.

The United Kingdom has subsidies from genuine attempts to address climate change 20 years ago.

“The entire industry is propped up by government subsidies,” Hillaker said. “Laws were put in place in Europe to increase renewable and decrease emissions. Draxes power plant (where some of Enviva’s wood pellets end up) uses 2 million pounds per day of wood pellets.”

Enviva is continuing to operate at Waycross while the company goes through a reorganization process, an option they chose after filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Unsurprised that Enviva filed for bankruptcy, Hillaker said they’ve been struggling for several months.

“In November they lost 80 million dollars,” she said.

“Enviva’s bankruptcy makes it even more clear that the U.S. should not waste taxpayer dollars on the polluting and failing biomass industry,” Hillaker said in the SELC press release. “Betting on biomass is a bad investment, plain and simple.”

For now, biomass/bioenergy remains a key part of Georgia’s long-term strategy and a “key element for our economy’s evolution,” Dartnell said.