Cindy White: What research says about locking up troubled teens and throwing away the key

Indianapolis attorney Charlie Asher said it was around Christmas in 1994 when Richard Doyle, then a member of the Indiana Parole Board, approached him with a request.

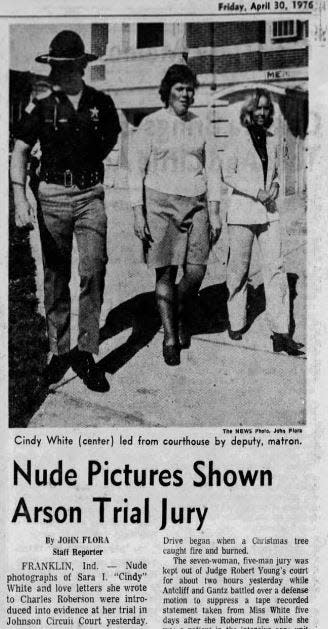

Doyle told Asher about Sarah "Cindy" White, who as a troubled teen in 1976 received six life sentences. He called it "the most unfair sentence you could ever imagine" and asked Asher to help the woman.

Asher has been working since then to free White, who was convicted of murder for starting a house fire that killed a Greenwood family. Charles and Carole Roberson and their four young children died in the fire on New Year's Eve of 1975.

Read the story: Justice or vengeance: At 18, she killed 6 in fire. Will Cindy White, now 66, die in prison?

Prosecutors portrayed White, the family's live-in babysitter, as a jilted lover who started the fire as revenge against Charles Roberson. But Asher argues there's far more to White's story than what jurors heard during her trial.

To him and White's other supporters, her case raises questions about the punitive value of life sentences, particularly for young first-time offenders, as well as the morality of permanently imprisoning a deeply damaged teenager whose mental and emotional growth was stunted by a long history of physical and sexual abuse ― a key part of White's story that jurors never heard.

What science says about sexual abuse and brain development

White initially denied starting the fire. But about a decade into her incarceration came a series of revelations.

She said her father began molesting her when she was 8, and another male relative started a more violent sexual abuse a few years later. As a teenager, the abuse at home forced her to seek refuge by living with the Robersons, who, she claimed, subjected her to even more abuse. She also admitted starting the fire, saying she meant only to damage the Robersons' house to force everyone to move out — and allow her to escape the alleged abuse.

Asher described White at the time as a "severely fragile and compromised" 18-year-old who had endured a decade-long molestation at home, who had been conditioned to never talk about it, and who had already tried to kill herself twice. White also had been diagnosed with conversion reaction, a mental health disorder that, in her case, caused paralysis and is often triggered by a traumatic event such as a history of childhood abuse.

Central to Asher's efforts to free White is research that didn't exist in 1976 about how this type of trauma can impair brain function and impede development, as well as a different societal view of sexual abuse.

Sexual abuse was largely an "invisible" issue in the 1970s, but is now an "obvious" concern for all issues related to problematic development, especially in girls, said James Garbarino, a psychology professor at Loyola University who studies how violence and trauma affect children. Today, if a patient is diagnosed with conversion reaction, sexual abuse is one of the first things a clinician would and should suspect and investigate, he said.

Garbarino also said childhood abuse "disturbs development." The severity of the impact depends on several factors, including how early the abuse happened, how long it lasted, and whether the child has other positive influences.

White had little positive influence in her life growing up. She said none of her doctors asked her if she was being abused at home, and she never brought it up after being rebuked when she reached out to her mother for help.

Marta Nelson, director of sentencing reform at the Vera Institute, said courts should consider a defendant's history with abuse. Those who commit violence, she said, are often victims of violence themselves. Nelson cited a new New York law that allows courts to resentence defendants who suffered from sexual, psychological and physical abuse that led to their convictions. Indiana doesn't have such a law.

Nelson also said there's another perspective to sentencing aside from punishment and retribution.

"That people are people. That with this person, there's a lot of extenuating circumstances," she said, referring to White. "That she's done what she's done to try to overcome them. That she should be judged by more than the worst thing she ever did."

But Lance Hamner, the prosecutor in Johnson County where White was convicted, has remained unconvinced.

"After all the speculation the fact remains that an 18-year-old woman intentionally set a fire in a home that she knew was occupied by a sleeping family that included four small children," he said. "And it killed those four little children and their parents. There is no excuse for that."

What does science say about maturity levels of young defendants?

Consistent in Asher's arguments is White's immaturity ― that although she legally was an adult at 18, years of abuse led to poor judgment and impulse control.

Settled science dictates that the brain is not fully mature until around mid-20s, and the legal community has started to recognize this. In 2012, a landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling found that mandatory life sentences without the possibility of paroles against juveniles is unconstitutional.

Garbarino said the 18-year legal line into adulthood is an arbitrary number that ignores their similar maturity level with their juvenile peers. He argues older teenagers and young adults should also have the same protections as juveniles from life imprisonment, regardless of the crime. But lawmakers and courts have been largely resistant.

"They mistakenly conclude that the severity of the crime is itself a predictor of a person's capacity and likelihood of rehabilitation. I don't know that there's really any evidence of that," he said. "There's much more malleability and changeability in teenagers. A lot of the bad stuff they do is transient."

Hamner acknowledges that brain development continues into the mid-20s, and he agrees that the criminal justice system should treat children differently from adults. But he rejects the "theory" that adults shouldn't be held fully liable for their crimes because they haven't completely matured.

"The objectives of the criminal justice system: deterrence ... rehabilitation, incapacitation, and retribution are best served when we recognize that despite our individual levels of maturity," he said, "adults must be held accountable for their crimes."

Has Cindy White been rehabilitated and will she reoffend?

Dr. Paul Shriver, a former staff psychologist for the Indiana Department of Correction, wrote the following in a Nov. 29, 1990, report supporting clemency for White:

"We whole-heartedly recommend favorable action on this appeal and can see no point to continuing her incarceration, either from a rehabilitative or a punitive standpoint."

That was 34 years ago.

Several others, including psychiatrists and counselors who have worked with White, echoed Shriver in their own reports. They said White has grown significantly. She has come to terms with her traumatic childhood, has shown great remorse and will not commit any more crimes.

In a 1994 report, Shriver described White as "highly employable," "very personable," and "usually cheerful."

Former Indiana Department of Correction employees also describe her as a model prisoner who immersed herself in various programs. Now 66, White uses a wheelchair after suffering multiple strokes and her activity at the prison is very limited.

It would be hard to argue White still poses a threat to society if she were to be released, said Jennifer Pealer, a criminal justice professor at East Tennessee State University. Housing someone in prison is also costly. In Indiana, it amounts to more than $19,000 a year.

"In one aspect ... is it worth it for the taxpayer to foot that bill?" Pealer said. "The opposing argument would be how much are you placing a value on life? She did kill six people."

Contact IndyStar reporter Kristine Phillips at (317) 444-3026 or at kphillips@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Cindy White: What research says on life sentences for troubled teens