Britain’s youngest Second World War prisoner in German camp saw boy shot dead whilst sharing soup

Britain’s youngest Second World War prisoner of war watched a Yugoslav boy being shot while they shared soup in a German camp, newly released National Archives records show.

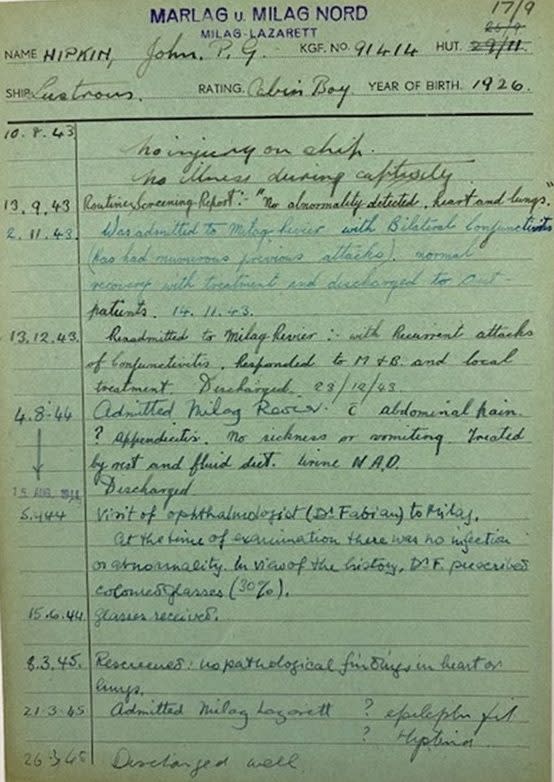

John Hipkin was 14 when he left Newcastle-upon-Tyne to be a cabin boy for the merchant navy during the war, as he was too young to join the Royal Navy.

According to his prisoner of war records, John was captured 21 days into his first wartime voyage when the oil tanker he was on was sunk by the German battleship Scharnhorst off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

His son Dominic Hipkin said: “The morning the ship was attacked dad said he saw the outline of a large battleship in the mist as he took the captain his breakfast, but mistook it for a British ship.

“When shooting started, the captain told Dad to go back to his cabin and get his life jacket.

“They got into the lifeboats and when they were rowing towards Scharnhorst they could see people on deck holding what they thought were machine guns.

“When they got closer they realised the German crew were filming them.”

Mr Hipkin and the rest of the crew were taken to Marlag und Milag Nord – a prisoner of war camp near the German sea port of Bremen whose commandant, Captain Prusch, was later charged with war crimes.

Documents revealed that he made prisoners run until they dropped from exhaustion and forced them to stand facing barbed wire for 14 hours with no food or water.

Dominic Hipkin said: “There was an unofficial arrangement with guards that British prisoners of war could share food with the Slavs, who were given very bad mouldy bread.

“They were told they were allowed to dip it into the British prisoners’ soup, but one guard picked up his rifle while this was going on and shot a young Yugoslav boy right in front of my father. They were the same age.”

Mr Hipkin was freed on his 19th birthday in 1945 when a British tank crashed into his camp and rescued him in time to arrive home on VE Day – more than four years after he was captured.

He was given a disability pension in June 1945 for the “effects of detention (hysteria)”.

In 2006 Mr Hipkin succeeded in getting posthumous pardons for more than 300 “deserter” soldiers who had been court-martialed for cowardice on the grounds that they had not been given a fair trial and many had been under-age.

Roger Kershaw, head of strategic operations at The National Archives, said: “It’s fascinating that we’ve been able to access John Hipkin’s records.

“It’s a rich resource that gives us more detail about his story and seeing a picture of John at that young age makes it more powerful.”

War records for Mr Hipkin, who died in 2016, and other prisoners of war, are available to see at The National Archives exhibition called Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives, which runs until July 21.