Author will speak in Columbia on Hubert Humphrey, fight for civil rights

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Though the Civil Rights Movement came to fruition in the 1950s and 1960s, one can arguably trace its roots to Hubert Humphrey's speech at the 1948 Democratic National Convention, advocating for adoption of a strong civil rights plank in the Democratic platform.

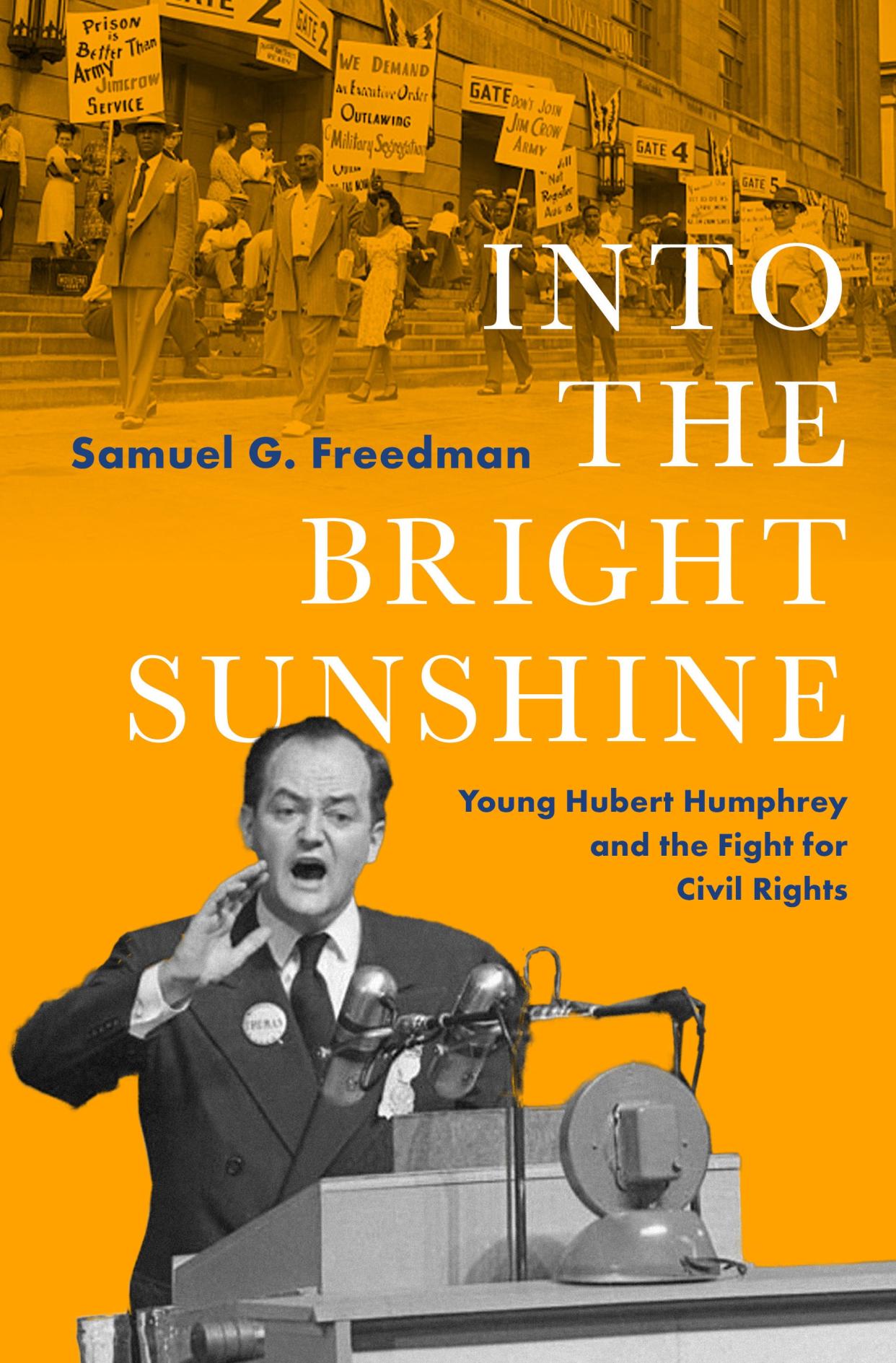

The speech is central to Samuel G. Freedman's book "Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights." It is published by Oxford University Press.

Freedman will talk about Humphrey at 2 p.m. Wednesday at the State Historical Society of Missouri, 605 Elm St.

Freedman, a professor at Columbia University in New York City, is a former columnist and staff writer for the New York Times.

Freedman takes his title from the text of the speech.

"My friends, to those who say that we are rushing this issue of civil rights, I say to them we are 172 years late," Humphrey said in July 1948 in Philadelphia. "To those who say that this civil rights program is an infringement on states' rights, I say this: The time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights. People — human beings — this is the issue of the 20th century. People of all kinds — all sorts of people — and these people are looking to America for leadership, and they're looking to America for precept and example."

Humphrey was the 37-year-old mayor of Minneapolis and a candidate for the U.S. Senate at the time.

The party unexpectedly approved the civil rights plank, and Harry Truman, widely expected to lose the election, ran on it. He quickly desegregated the military and the federal workforce.

Franklin Roosevelt had made inroads into the Black vote with his new deal programs, but Black voters at the time usually favored Republicans dating back to the time of Abraham Lincoln, Freedman said in a phone interview.

"He made a devil's bargain with Southern segregationists in return for their support of New Deal programs," Freedman said of FDR.

It was untenable to continue to support the segregationists in 1948, Freedman said.

"Black G.I.s had returned from World War II, seeking the 'double V', victory over fascism abroad and victory over Jim Crow at home," Freedman said.

Truman had begun to backtrack on civil rights, but the plank gave him no choice, Freedman said.

"In the aftermath, Truman wins the election because of the surge of Black voters," Freedman said. "It was absolutely essential to Truman in 1948."

It can legitimately be called the start of the Civil Rights Movement, Freedman said.

"It was a pivotal moment in the nation and it really anticipated the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and the Montgomery bus boycott the following year," Freedman said.

The previous year, a Neo-Nazi opposed to Humphrey's efforts to integrate Blacks, hid outside his Minneapolis home with a gun. When the would-be assassin fired, he missed, Freedman said.

There's more to Humphrey's story, though Freedman's book focuses on 1948 and his early life.

Lyndon Johnson chose Humphrey as his vice president to show members of the Kennedy administration he was serious about civil rights, Freedman said. Johnson became president when John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 and ran for election in 1964.

Humphrey was instrumental as floor manager in breaking a filibuster to gain passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, then the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1966.

"He was absolutely essential as vice president," Freedman said.

"If the 1948 Democratic National Convention was Humphrey at his best, the 1968 Democratic National Convention was Humphrey at his worst," Freedman said.

It was a chaotic year with the Democratic Party and the nation fractured over the Vietnam War. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King had been assassinated.

Johnson had decided not to run for another term.

The convention itself, in Chicago, was marred by police violence against Vietnam War protesters.

The police violence wasn't Humphrey's fault, but he remained silent about it, Freedman said.

The convention hardened the public idea of Humphrey as a product of the political machine, he said.

Humphrey didn't run in any of the primaries in 1968.

"The party machine gives him the nomination," Freedman said. "His acceptance speech about the politics of joy is completely tone-deaf."

He is reviled by the political left.

With all this, the election that pitted him with Richard Nixon was one of the closest in U.S. history, with Nixon receiving 43.4% of the vote, Humphrey, 42.7% and George Wallace, 13.5%.

Humphrey later said not opposing Vietnam was his gravest mistake, Freedman said.

It's speculation, but Freedman said a few things may have tipped the election in favor of Humphrey.

First, the administration and the FBI had learned of the Nixon campaign's interference in the Vietnam peace talks, causing the South Vietnamese to walk out.

Humphrey and LBJ knew about it, but decided to keep quiet because it was so close to the election and they decided it would look bad if they revealed it, Freedman said.

"They decided not to go public with it," he said.

Information about the events has been fully revealed since.

"That's settled history," Freedman said.

Peace candidate Eugene McCarthy gave Humphrey a tepid and begrudging endorsement shortly before the election, Freedman said.

It essentially signaled to McCarthy's supporters that voting for Humphrey wasn't important, he said.

Humphrey died in 1978 at age 66.

Roger McKinney is the Tribune's education reporter. You can reach him at rmckinney@columbiatribune.com or 573-815-1719. He's on X at @rmckinney9.

This article originally appeared on Columbia Daily Tribune: Author of Hubert Humphrey biography to speak in Columbia Wednesday