The Oscar-Nominated Filmmaker Behind ‘O.J.: Made in America’ on His Oscars Night Plans and Why O.J. Still Matters

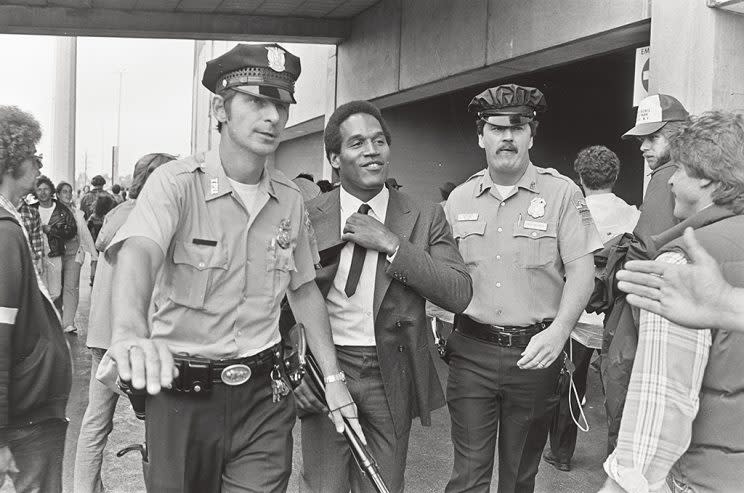

Since it debuted at the Sundance Film Festival last January, critics have been hailing Ezra Edelman’s five-part ESPN documentary O.J.: Made In America as one of the best films of the year. Nominated for an Oscar in the Best Documentary Feature category, the opus charts the rise and fall of an American icon — from his glory days as a beloved football hero and pitchman to his darkest hours following the double murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman on June 12, 1994, and the trial that followed. On another level, it is also an allegory about race, unrest, media, and fame in America. At times, it’s hard to look at, but it’s even harder to look away — a feeling that’s eerily reminiscent of that infamous televised white Bronco chase.

Whatever you thought you knew about the O.J. Simpson story, this film will make you think again, and more deeply, about the trial of the century and all of the players involved, many of whom Edelman, 42, tracked down and interviewed. “I wasn’t out to assign blame. I wasn’t out to say, ‘You f***** up,’” Edelman says. “It was just like, ‘Here’s the story. And by the way, it’s history, and you’re a part of it.’ ”

We spoke to Edelman about his film and what compelled him to make it.

Yahoo Movies: Where were you in the summer of 1994?

Erza Edelman: I was in Washington, home for the summer after my sophomore year in college. I mean, June 12 itself was meaningless. I couldn’t tell you my memory of hearing about the murders.

Do you remember watching the Bronco chase?

Oh, yeah. Friends were coming over to watch the NBA finals, and so there were a lot of people at my house. We turned on the TV to watch — and there was O.J. in his white Bronco on the 405, and it was sort of stunning to see a guy who — I mean, it was O.J. I had the same feeling about him that I’m sure millions of people did. So there was the immediate dissonance of, “Well, it’s not possible that he’s responsible for this.” It was just bizarre, surreal circumstances. And, frankly, at a certain point while that was going on, the game was going to start, and I remember a few people being glued to the TV watching O.J. And I was like, “OK, I’m going to go downstairs now to the other TV.” I was more interested in the game.

You’ve talked about what O.J. meant to you as a kid. What did you like about him?

I was a huge sports fan as a kid, and I played a lot of schoolyard football. I was 5 years old when he retired from football, so it’s not as if I watched him play in real time. But [I saw] the highlights of him playing for the Buffalo Bills. I was very attracted to just him as this athletic god; the balletic way he made his way down a football field was very alluring to someone who was fascinated by sports and athletes. Being in an airport terminal with that ongoing traffic, and [remembering] that feeling I would have of, “All right, I’m going to be like O.J.,” and you kind of dodge and bob and weave through these people. That was a very clear thing I remember thinking and doing. From a representation standpoint, there also weren’t that many black people on TV. For me, O.J. was this wonderfully benign, amusing presence on my television, whether it was in Hertz commercials or going to the movies and seeing Naked Gun.

I don’t follow football, but I watched O.J. run down that field, and it was beautiful. Were you trying to make the film for sports lovers as well as for viewers who don’t care about football?

I think it’s very important to have people reconnect with that beauty and appreciate those gifts. You’re seeing them for the first time and you can go, “I get it.” Part of it is reconnecting with him emotionally and understanding the hold he had over people. [It’s important] to see how handsome and charming he is, the superficial beauty. Essentially, to be seduced by him all over again. … It’s not as if I needed to restore that for the sake of fairness. It’s to help explain why people were aligned with him and in such disbelief. You needed to understand that. To go back and see this guy, the goodness, the seeming purity of him, was very important to me.

Everybody thought that they knew him, but clearly they didn’t. You did more than 70 interviews in all. Who has come out of the woodwork since? I know Chris Darden, who was on the prosecution team, declined your request. Why do you think prosecutor Marcia Clark agreed?

I mean, she hadn’t done an interview in 20 years. I think if you asked her, she would tell you matter-of-factly that this wasn’t something she wanted to do, and she was reluctant to do it. Because she, like everyone else involved in the trial, had been bothered ad nauseam. Every year, there are these anniversaries, people calling. There’s like a cottage industry that has risen up around O.J. and the story.

Especially around the anniversary, right? [October 2015 marked 20 years since Simpson’s acquittal.]

Especially that. A lot of things were being done concurrently, and going in, I understood that from both the juror standpoint and the prosecution standpoint, people were going to be reluctant to talk. There were four main people on the prosecution, and I thought, “Well, if I could get one person, [Chris] would be the person I’d want.” I really tried hard with him. I read his book and wrote him a personal letter and called him a couple of times, but he just didn’t respond.

What about Simpson? You wrote him but never heard back. Still no word since the movie’s release? I mean, he’s the missing link here.

No, I have not heard from him. I’m fine if I never hear from him.

Have you heard from family members?

No, I haven’t heard from anybody.

Maybe it’s a “no news is good news” kind of thing.

I do not disagree.

I wanted to ask about Johnnie Cochran, the Simpson defense attorney who died in 2005. I didn’t know the richness of his experience as a civil rights activist and lawyer. Why did you decide to spend so much time on him? And were you surprised to learn about his history?

I think he is reflective of a lot of the things that became a part of this story: How [the main players] became these one-dimensional characters framed in a certain way during this trial that essentially became a reality show. I knew a little bit about him. I know he had a certain depth beyond how he’s been described as a “racial huckster.” He had spent his entire career trying to fight for the rights of people who had suffered abuse at the hands of cops in Los Angeles. This had been a galvanizing issue for him. … He’d really been rooted in the black community — a hero who had fought for the rights of his rank-and-file African-Americans for decades.

And then he arrives at this point in time in the mid ’90s, and he has become a celebrity lawyer. He does wear fancy suits. He does enjoy the limelight. In terms of what motivated him and what he truly believed, who knows? All these people, they bring their history to this story. They brought their history to this trial. And if you don’t understand who they were and where they came from, you don’t quite get what was going on. You don’t get the richness of the story. Would I have loved to talk to Johnnie Cochran if he were alive? Of course. All I can do without having that opportunity is try to offer as fair a portrayal as possible.

Watch a trailer for the documentary:

In recent years, Black Lives Matter has become a movement and a national rallying cry. When you were making the film, did you anticipate some of the conversations we’re having now?

The spate of incidents that have happened in the last few years were happening concurrently to when we were making the film. It was a coincidence. I mean, the story that I was telling was the story I was telling, trying to shed light on this dynamic that had plagued [L.A.] and the black community here for decades. This conversation rose up because of what had happened — first with Trayvon Martin, then with Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and so on. I’m very happy that people have engaged with this issue, but again, it’s like the lesson in the film: Because George Holliday had a videotape and taped Rodney King getting beaten, all of a sudden it was like, “Wait, this happens?” And people have been like, “This has been happening for decades. This happens every day.” So, there’s a little bit of the same idea: This issue should have always been timely, and it has been. It’s just that we don’t, as a culture and as a society, focus on it the way we should.

Let me ask about Black History Month for a second, specifically Donald Trump’s Frederick Douglass gaffe.

Oh, my God.

Yeah, what did you make of that?

This whole thing is so beyond surreal. But there are these moments when, again, you think of our complicity as a culture in the rise of O.J. Because of that seduction, because of how he made us feel, that speaks to the dissonance … you kind of are still rooting for a guy because he once brought you joy watching him run a football. But on the other end of it is the footage of people — after you’ve seen a guy on trial for murder, after you’ve seen him be found responsible in a civil trial — coming up and wanting his autograph. Wanting to hug him. Wanting to be in his presence. Wanting to be aligned with someone who is famous. That is so troubling.

On a very different note, what are your Oscars plans?

I’m bringing one of our producers. There are so many people who worked on the film and were so crucial. We had three producers, three editors, and there’s a finite amount of tickets. So I want to make sure as many people get to enjoy this potentially once-in-a-lifetime experience as possible.

Watch a video about the 2017 Oscars by the numbers:

Read more: