Brazil's Ecosystems Are Under Threat — but These Eco-lodges Are Trying to Save Them

The vast, varied landscapes of Brazil are home to creatures like the jaguar, the spider monkey, and the maned wolf. These three eco-lodges are leading preservation efforts to help the animals make a comeback.

Carmen Campos

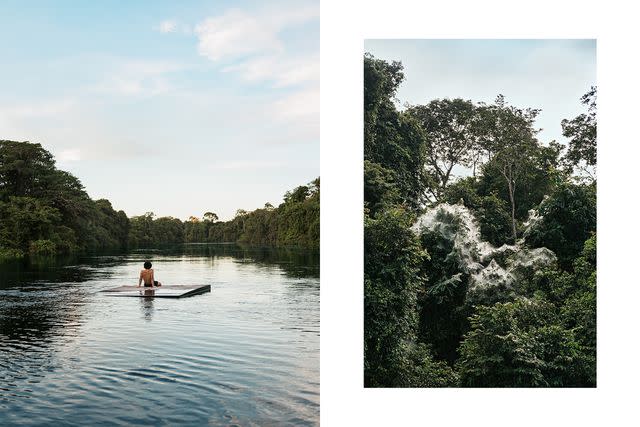

A bird's-eye view of the Cristalino River, in the southern Amazon.Going up the Amazon River, it was easy to imagine the world was still brand new, untouched by progress or technology. Our little boat was like a time machine, the millennia falling away beneath the bow. This must be how things were at the beginning, I thought, before the arrival of mankind.

Birdsong rang from the jungle. A half-submerged caiman, the South American cousin of the alligator, watched us from the shadows of the bank, only its eyes visible. A giant river otter surfaced with a half-eaten fish. Spider monkeys, dancing through the trees, suddenly stopped to gaze down at us.

Amazonia, the famed 2.5 million-square-mile rainforest, is never just a destination. In the popular imagination, it’s an image of prelapsarian wilderness — and the manifestation of our environmental nightmares. According to satellite data, an estimated 110,000 square miles of rainforest in Brazil (an area the size of Nevada) have been lost this century so far, much of it to monoculture agribusiness. And the pace of deforestation, which had been slowing, spiked under the administration of the anti-conservation president Jair Bolsonaro, which lasted from 2019 to 2022.

Carmen Campos

Taking in the Cristalino River, in the Amazon rainforest; webs woven by social spiders in the Cristalino Private National Heritage Reserve.But I had come to Brazil to explore a more hopeful narrative, to learn how conscious travel can be a tool in the pursuit of habitat protection and wildlife conservation. I visited three eco-lodges that run preservation programs in the country’s most vulnerable habitats: the central Cerrado savanna, the southwestern Pantanal wetlands, and the sprawling Amazon rainforest. At each property, surrounded by natural beauty, visitors are encouraged to learn about and help protect these remote biosystems and the species that live there.

The Cerrado Grasslands — Pousada Trijuncao

The Cerrado is a vast, empty-seeming place — largely forgotten, even by Brazilians. A tropical savanna, it is the second largest habitat in Brazil after the Amazon and, depending on how it’s measured, accounts for roughly a fifth of the country’s landmass. Amid vast skies and limitless horizons, empty sand roads run mile after mile.

But there is nothing bleak about the wildlife in this remarkable environment. The World Wildlife Fund has named Brazil’s Cerrado the most biodiverse savanna in the world, with 11,000 plant and 200 mammal species, 20 of which are endemic. Yet for all its biological riches, the area is under threat, disappearing at twice the rate of the Amazon forest. Industrial farming, chiefly for soybeans, has seen exponential growth in the past 25 years, supported by the use of harmfully high levels of lime and phosphorous fertilizers. Only about a fifth of the Cerrado’s original area remains intact. Some experts fear the grasslands may disappear completely in the coming generations.

Carmen Campos

The lounge at Pousada Trijunção, in the Cerrado savanna; on an evening game drive, guides at Fazenda Trijunção scan for maned wolf tracks.One leader of the conservation efforts here is Fazenda Trijunção. The fazenda — the word means “ranch” or “farm” in Portuguese — supports environmental projects that preserve the surrounding landscape and explore nondestructive agricultural practices, such as growing fruit trees and implementing sustainable grazing patterns. It also runs Pousada Trijunção, a seven-room lodge that, in addition to providing employment for locals, is drawing travelers’ attention to the Cerrado and its wild inhabitants.

"The most iconic and elusive star of the Cerrado is the maned wolf. With its long legs and reddish fur, this remarkable creature looks more like a small deer than a canine. There are thought to be only 17,000 adults left in South America, a number that’s diminishing all the time."

Pousada Trijunção’s clay airstrip can be reached by an hourlong flight directly from Brasília. Stylishly constructed from sustainable materials, the lodge has the feeling of a sleepy outpost, a place of hammocks, home cooking, and the world’s best caipirinhas. The rooms are quirky — decorated with plants and art by local artisans — yet still feel luxurious. The property’s hot water is heated by solar energy. On languorous afternoons, I watched swallows dive over the surface of the swimming pool as guinea pigs scampered around the courtyard. In the early mornings, I climbed to the top of the site’s observation tower with ornithologist Vinicius Vianna to scout fabulously colored birds: red and green macaws, peach-fronted parakeets, and toucans.

But the most iconic and elusive star of the Cerrado is the maned wolf. With its long legs and reddish fur, this remarkable creature looks more like a small deer than a canine. There are thought to be only 17,000 adults left in South America, a number that’s diminishing all the time; 90 percent of those are in Brazil. The primary threat to their survival is shrinking habitat. The Cerrado remains one of their chief domains, though they are also found in Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru. Few people have seen the maned wolf, but its smell may be familiar to many — the scent of their urine markings is commonly mistaken for cannabis.

Carmen Campos

Enjoying a swim in Pousada Trijunção's outdoor pool.Tracking and recording the wolves’ behavior is the focus of a project run by Onçafari, a Brazilian conservation NGO that has partnered with Fazenda Trijunção. At dusk, I set off in a jeep through low scrubland with two Onçafari guides, Bárbara Couto and Isabela Meniz.

“They are generally solitary creatures,” Meniz said of the maned wolves. “And when they mate, both sexes are monogamous.” But Nhorinha, an alpha female in the area, refused to be tied down by the conventions of her species. “She has taken at least three partners that we know of,” Couto smiled. “We like her.”

Related: This Brazilian Beach Destination Is a Quieter, Laid-back Alternative to Rio de Janeiro

Couto and Meniz tracked Nhorinha by the signal of her radio collar. When they spotted a line of paw prints in the soft sand, we followed them deeper into the Cerrado, under a lowering sky that gave off a strange, pewter-tinged light. A pampas deer came into view, still as a statue in the long grass, before starting and bounding away. A stygian owl perched on a branch, waiting for dark.

Carmen Campos

A guide at Fazenda Trijunção preserve scans for birds in the Cerrado savanna.The three of us continued for an hour while the dusk thickened until suddenly, as we came around a bend, there she was. Nhorinha trotted ahead of us: long-legged, elegant, slender, her tail a flash of white. In that gray, uncertain twilight, she might have been a ghost. She stopped in the track and turned to look over her shoulder. For a long moment, those haunting eyes looked straight at our vehicle, assessing us. And then she disappeared, the road suddenly empty.

Several months after my trip, I received tragic news from Couto and Meniz. Nhorinha was gone; she and two of her pups had drowned in a drainage ditch on neighboring farmland. The Onçafari team was devastated. But that same month, the researchers made a new discovery. On their usual rounds, they spotted Savana, Nhorinha’s two-year-old daughter, with three new cubs. “The wolves teach us to be resilient,” Meniz said when I spoke to her on the telephone. “And to never lose hope.” Their work at Pousada Trijunção feels more vital than ever.

The Pantanal Wetlands — Casa Caiman

Heading to another vulnerable region, I flew south in a small plane, landing on the edge of a lake deep in the Pantanal. The water’s surface shone in the bright sunshine and trees threw intricate shadows on the ground. The day felt fresh and full of promise.

Carmen Campos

Sundown at Caiman, an ecological reserve in Brazil's Pantanal wetlands.Threaded by meandering rivers, the Pantanal is a wetland that’s 16 times larger than the Florida Everglades. In the wet season, when the streams break their banks, much of the region’s savanna and scrub floods, and many animals migrate to wooded islands marooned among the sheets of shallow water. The biodiversity is astonishing — the species list consists of more than 600 birds, around 100 mammals, and myriad reptiles and amphibians. unesco has declared it a Biosphere Reserve. But curiously, the Pantanal is also ranching country. For well over 200 years, herds of white cattle, weathered corrals, and cowboys on horseback have coexisted, a little uneasily, with teeming wildlife.

In the mid 1980s, conservationist Roberto Klabin inherited some of his family’s ranchland, ultimately amassing the 131,000 acres in southern Pantanal that make up the Caiman ecological reserve. Part of the property has been fenced and set aside as a government-protected nature preserve, but most of it remains open, allowing cattle to continue living on the land.

At the south of the estate, the 18-suite Casa Caiman welcomes travelers with an aesthetic poised somewhere between western chic and Caribbean luxury. Sand-yellow walls and rust-red rooftops help the buildings blend naturally into the surrounding landscape. The bedrooms and living rooms are spacious and uncluttered; there are leather armchairs to sink into, sprawling sofas, piles of books about Brazilian wildlife, and decorative details from Andean textiles to contemporary art.

Carmen Campos

Guests at Casa Caiman take a sunset canoe tour in Brazil's Pantanal wetlands.Over a meal with my guide, Murilo Frasão, the conversation spanned a hyacinth macaw rescue program, the sex life of capybaras, and the sticky tongue of giant anteaters — two feet long and able to flick in and out 150 times per minute. He told me about jaguar lore, including the traditional Indigenous belief that the big cats carry the souls of deceased shamans. Then we gathered our binoculars and cameras and headed out.

As we drove north on a red dirt road in Caiman’s open jeep, Frasão explained that ranchers and jaguars have clashed violently for more than two hundred years: the jaguars killed cattle and the ranchers hunted jaguars. A 1967 ban on hunting initially did little more than convert hunters into poachers. But half a century on, jaguars are now seen as contributors to the local economy. Wildlife tourism has brought quality jobs, infrastructure improvements, and funds for education and health facilities. A compensation program run by Caiman helps mitigate livestock losses. At the same time, conservation efforts have helped increase the populations of the jaguar’s natural prey, alleviating their need to hunt cows. Some poachers in the Pantanal have opted for a career change: now, they’re sought-after guides.

Carmen Campos

Scouting for wildlife in the early morning atop Cristalino Lodge's observation tower.These efforts come at a much-needed time for the cats. Few people in South America have actually seen a jaguar in the wild — famously elusive, their numbers are in decline. As jaguar territories from northern Mexico to Argentina continue to shrink because of human activity, their population is thought to be down by 25 percent since the 1990s. But there are approximately 3,000 to 5,000 jaguars in the Pantanal — a relatively high concentration. That, plus the gradual introduction of radio tracking collars starting in 2011, now makes the Pantanal one of the best places in the world to see them.

As Frasão and I scanned a watery bank lined with broom sedge, we could see vultures turning slowly in the sky. We left the road and drove through yellow-green grass toward the birds, scanning the horizon with binoculars. Before us, pink clouds were rising like loaves in the late-afternoon heat. Four balletic rheas — South American cousins of the ostrich — passed, their feathers flouncing like tutus. A giant anteater appeared, heading for a termite mound, its long hair trailing like an elaborate Victorian gown. Then, through the vegetation, the silhouettes of jaguars appeared. We approached downwind, gradually bringing the vehicle closer. A mother and two cubs were feeding on the carcass of a cow, probably killed earlier that day. The guide knew them. The mother was Surya, born in 2018; her cubs, probably six months old, were Jeronimo and Juba.

Carmen Campos

Surya, a female jaguar in the Caiman ecological reserve, wearing a GPS tracking collar.When the three cats had eaten their fill, they retreated to lie in the grass, resting, snoozing, playing. The cubs tumbled over one another, and then tumbled over their mother, until they tired and fell asleep suddenly, like toddlers. After a rest, they returned to the feast, ready for the next course.

We left them in the failing light and went home on a dark road, listening to the nighttime chorus of droning insects and frogs. With the cooling air, aromas assailed us in the open vehicle: some sweet, unnamed blossom; animal dung; the rich smell of earth.

Related: São Paulo Has Become Brazil's Most Stylish City

Later we went to an evening churrasco, a barbecue organized by ranch hands. Sides of beef sizzled over an open fire, pitchers of rough red wine were produced, and a country band — guitars and an accordion — sang about love and loss. It struck me that these vaquieros, or cowboys, are as much a part of this landscape as the jaguars. Now, with a little help from conservationists and an income supported by conscious tourism, they are learning to share it.

The Amazon Rainforest — Cristalino Lodge

My final destination in Brazil was the Amazon — specifically, the Cristalino Private National Heritage Reserve. Created by the conservationist Vitória Da Riva Carvalho, the sanctuary stretches across more than 28,000 acres and, together with the neighboring Cristalino State Park, is one of the most important areas of biodiversity in the entire rainforest. Between 2006 and 2008, a research program there logged 1,356 different plant species, including six that had never been recorded before.

Landing in the town of Alta Floresta following two short flights from São Paulo, I was met by a 4 x 4 that took me north on dirt roads, past logging camps and fields. Eventually the rickety ranch houses and agriculture fell away and trees began closing in on all sides. At the Teles Pires River, there was a small boat waiting. We headed upstream between thick banks of jungle; an hour later, I sat down to a sumptuous lunch in the open-sided dining hall of Cristalino Lodge.

Carmen Campos

From left: Locally sourced açaí bowls by chef Fábio Vieira at Cristalino Lodge; horseback riding at Caiman, an ecological reserve in western Brazil.Spread out among flower beds and forest paths, the lodge is a collection of small bungalows, with hammocks strung on the porches. The furnishings are comfortable rather than stylish, perhaps because the point isn’t to lounge inside — visitors are assigned their own naturalist guide for twice-daily forest treks and river trips.

In the predawn air at breakfast, I could hear howler monkeys whooping three miles away; their call is said to be one of the loudest sounds in nature. In the evenings, I listened to the call of the tiny Snethlage’s marmoset: so discreet, so delicate, it sounded like birdsong. On the hikes, everything I saw, from the rare tree frogs to the legions of ants and the butterflies the size of dinner plates, was part of an ecosystem of astonishing complexity.

"Going up the Amazon River, it was easy to imagine the world was still brand new, untouched by progress or technology. Our little boat was like a time machine, the millennia falling away beneath the bow. This must be how things were at the beginning, I thought, before the arrival of mankind. "

But it was the river I loved, the boat excursions upstream and down. People fall for rivers, and I had fallen for the Cristalino — the boat gliding over the surface, the trees trailing branches seductively in the current, the endless soundtrack of shrieks, croaks, and whistles. I loved the way the eddies and currents of the water were burnished with light at midday, and the way the mirrored surface of reflected cloud and blue sky made it feel as if we were in midair, flying.

Carmen Campos

A walk amid ancient Brazil-nut trees in the Amazon rainforest; spider monkeys in the treetops at the Cristalino reserve.On my last morning, I headed upriver with a guide. We passed capybaras standing belly-deep in the shallows. Through the leaf cover, I spotted a tapir, almost twice the size of a pig. By an island bank, we pulled the boat in to examine a massive anaconda, as thick as a man’s thigh, coiled around itself. We spotted a river otter fishing, gliding through the water, then hauling itself out on a half-sunken log to eat his breakfast catch, so close we could hear the crunch of fish bones.

In the trees along the banks were families of white-cheeked spider monkeys. Endemic to Brazil, they are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. A study in 2008 discovered that their numbers had decreased by 50 percent in the span of just three generations because of hunting and habitat loss from deforestation, road construction, and soybean production. The Cristalino reserve has become a lifeline for this species, allowing them to exist there unthreatened by further encroachment. The monkeys swung down through the branches like a circus act, their tails acting like a fifth limb. A tiny youngster gazed wide-eyed at us through the leaves, his brow knitted in an expression of puzzlement. We were almost certainly the first humans he had ever seen.

Related: Salvador's Afro-Brazilian Culinary Culture Is Thriving

We even spotted a hoatzin, a bizarre-looking crested bird that seems more at home in a Jurassic world of dinosaurs than the present day. Hoatzin hatchlings have claws on their wings, like the archaeopteryx, the feathered dinosaur — the claws enable the chicks to climb trees before they can fly.

No one can be sure how ancient this species is, how many generations of hoatzin have perched in these trees. What is clear is that their survival, like that of the spider monkeys, the jaguars, the maned wolves, and so many others, depends on us. Humans and habitat destruction are the chief threat to every animal I saw on this remarkable journey, but low-impact travel, with responsible lodges and operators, is one of the ways we can support them. Thoughtfully managed travel helps preserve animal habitats for future generations — theirs, and ours.

Carmen Campos

Turquoise-fronted parrots soar above the Cerrado.Where to Stay

Casa Caiman

This 18-suite lodge in the Pantanal wetlands is located in the Caiman ecological reserve, home to a robust jaguar population. The property has a swimming pool framed by palm trees, outdoor firepits, and even an impressively equipped gym. The six-bedroom villa, Baiazinha, is an option for those who want more space and privacy.

Cristalino Lodge

These eco-friendly bungalows in the Amazon rainforest’s Cristalino Private National Heritage Reserve were designed to promote natural ventilation and have solar water-heating systems. At the restaurant, splendid meals incorporate local ingredients like açaí, banana leaves, and cassava. Wildlife abounds on the daytime excursions, from spider monkeys to river otters.

Pousada Trijunção

Visitors stay at this lodge in the Fazenda Trijunção preserve for game drives to spot maned wolves, kayaking excursions, and fat-bike tours in the surrounding Cerrado region. Under a terra-cotta roof, the seven jungle-chic rooms are decorated with rough-hewn wood paneling and art made from natural materials.

How to Book

Niarra Travel

The experts at this U.K.-based company can arrange conservation itineraries that include stops at Brazil’s best eco-lodges, park fees, daily guided excursions, and even a comfy hotel in Rio de Janeiro to bookend the trip.

A version of this story first appeared in the April 2024 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Nature's Keepers."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.