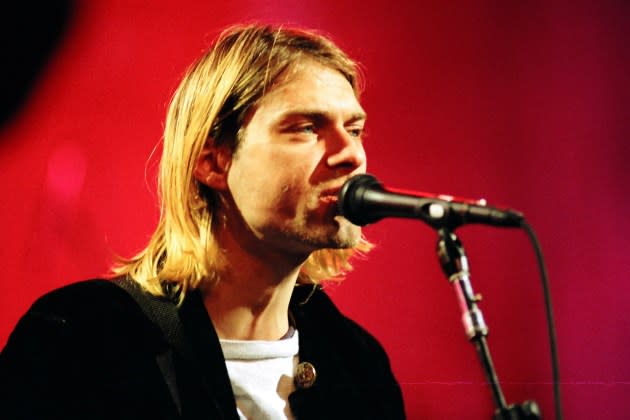

Kurt Cobain: 1967–1994

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Kurt Cobain never wanted to be the spokesman for a generation, though that doesn’t mean much: Anybody who did would never have become one. It’s not a role you campaign for. It is thrust upon you, and you live with it. Or don’t.

People looked to Kurt Cobain because his songs captured what they felt before they knew they felt it. Even his struggles – with fame, with drugs, with his identity – caught the generational drama of our time. Seeing himself since his boyhood as an outcast, he was stunned – and confused, and frightened, and repulsed, and, truth be told, not entirely disappointed (no one forms a band to remain anonymous) – to find himself a star. If Cobain staggered across the stage of rock stardom, seemed more willing to play the fool than the hero and took drugs more for relief than pleasure, that was fine with his contemporaries. For people who came of age amid the greed, the designer-drug indulgence and the image-driven celebrity of the ’80s, anyone who could make an easy peace with success was fatally suspect.

More from Rolling Stone

Whatever importance Cobain assumed as a symbol, however, one thing is certain: He and his band Nirvana announced the end of one rock & roll era and the start of another. In essence, Nirvana transformed the ’80s into the ’90s.

They didn’t do it alone, of course – cultural change is never that simple. But in 1991, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” proved a defining moment in rock history. A political song that never mentions politics, an anthem whose lyrics can’t be understood, a hugely popular hit that denounces commercialism, a collective shout of alienation, it was “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” for a new time and a new tribe of disaffected youth. It was a giant fuck-you, an immensely satisfying statement about the inability to be satisfied.

Photos: Rare Kurt Cobain Images, Artwork and Journal Entries

From that point on, Cobain battled to make sense of his new circumstances, to find a way to create rock & roll for a mass audience and still uphold his own version of integrity. The pressure of that effort deepened the wounds he had borne since boyhood: the broken home, the bitter resentment of the local toughs who bullied him, the excruciating stomach pains. He sought purpose in fatherhood. He wanted to soothe in his daughter, Frances Bean, his own primal fears of abandonment. He managed, finally, only to perpetuate them.

Cobain’s life and music – his passion, his charm, his vision – can be understood and appreciated. His death leaves a far more savage legacy, one that will take many years to untangle. His suicide note and Courtney Love’s reading of it say it all. In his last written statement Cobain reels from cracked-actor posturing (“I haven’t felt the excitement . . . for too many years now”) to detached self-criticism (“I must be one of those narcissists who only appreciate things when they’re alone”) to self-pity (“I’m too sensitive”) to a bizarre brand of hostile, self-loathing gratitude (“Thank you all from the pit of my burning, nauseous stomach”) to, of all things, rock-star cliches (“It’s better to burn out than to fade away”).

Kurt Cobain’s Downward Spiral: The Last Days of Nirvana’s Leader

Left with that, Love careens from reverence (“I feel so honored to be near him”) to pained confusion (“I don’t know what happened”) to exasperation (“He’s such an asshole”) to anger (“Well, Kurt, so fucking what? Then don’t be a rock star”) to sobbing, heartbreaking guilt (“I’m really sorry, you guys. I don’t know what I could have done”).

No answers are forthcoming, because there are none. Suicide is an unanswerable act. It is said to be the one unforgivable sin, though our age has sought to forgive it by explaining it away in psychological or chemical terms. Earlier eras were not so kind. Suicides were buried at the crossroads. The message was severe: You were at an impasse in your life and lacked the faith to make your way through it. Our lives are no easier to bear than yours. We may fall, but you chose to fall. We will make our way over you down the road of our destiny.

But suicide sends its own remorseless message. True, it is the ultimate cry of desperation, more harrowing than any scream Cobain unleashed in any of Nirvana’s songs. True, he was in agony and saw no other way to end it. But suicide is also an act of anger, a fierce indictment of the living. If the inability to live is “sensitive,” the ability to live comes to seem crass. “You’re so good at getting over,” the final message runs. “Get over this.”

At 27 years old, Kurt Cobain wanted to disappear, to erase himself, to become nothing. That his suicide so utterly lacked ambivalence is its most terrifying aspect. It all comes down to a stillness at the end of a long chaos: a young man sitting alone in a room, looking out a window onto the Puget Sound, getting high, writing his goodbyes, pulling a trigger. You can imagine the silence shattering and then collecting itself, in the way that water breaks for and then envelops a diver, absorbing forever the life of Kurt Cobain.

Best of Rolling Stone