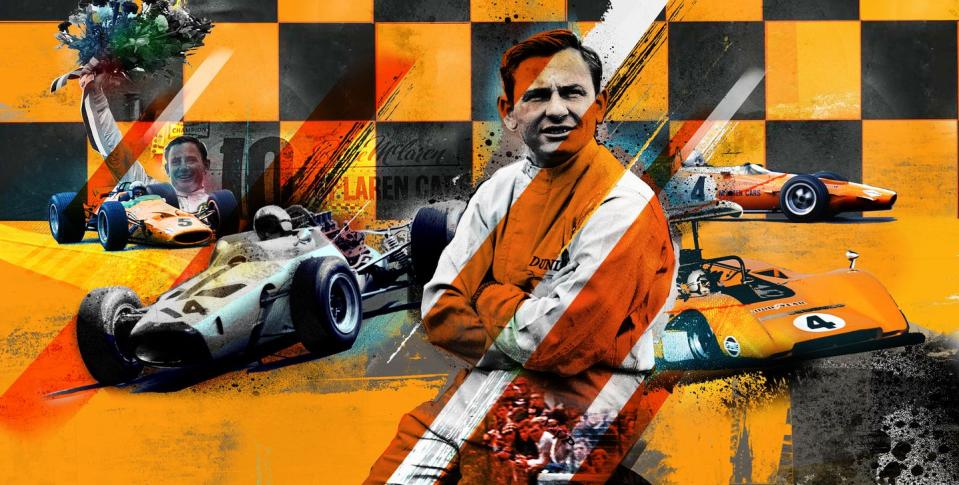

The Legend of Bruce McLaren

I was watching the Formula season 1 finale at Abu Dhabi with a group of race fan friends—some old-timers, others kids who’d been turned on to the sport recently by the doc series Drive to Survive—when one of the kids, a Lando Norris fan, made a casual comment while watching Norris running mid-pack in his McLaren Mercedes.

“I wonder where the McLaren name comes from,” this ten-year-old said.

The awkward silence of the half-dozen people in the room was shattered by the sound of my jaw hitting the floor. It turned out no one in the room knew the story of Bruce McLaren, a story so profoundly human and so important to motorsport that I felt it was necessary to share it immediately.

Bruce McLaren’s contributions to racing in the 1960s helped to build the sport into what it is today. Because of Bruce, the name McLaren is still synonymous with brilliance more than 50 years after his tragic death.

His story began in the most unlikely of places: the Wilson Home for Crippled Children in Auckland, New Zealand. As a kid McLaren was diagnosed with Perthes Disease, a rare condition affecting the development of the hip bones. He spent two years strapped to something called a Bradshaw Frame, basically a bed on wheelchair wheels. Young Bruce started racing down the hallways of this convalescent home against other kids on Bradshaw Frames. If you were to dream up a story about an underdog kid who comes out of nowhere to become a great race car driver, this would be pretty a good beginning.

He eventually got out of the Wilson Home with one leg significantly shorter than the other, for which he would always need corrective footwear. When he started racing, he would limp heavily in his racing shoes, one of his defining physical characteristics in pit lane. The other was his extraordinarily warm, disarming smile.

McLaren’s father owned a gas station, and he helped Bruce get started in an Austin 7 Ulster. Then, in the late 1950s, F1 pilot Jack Brabham, who was already making a name for himself in Europe came home to NZ to run a few races and was offered a place to stay in the McLaren house. In pretty much no time, Brabham had discovered young Bruce and brought him to Europe to race for the Cooper team.

McLaren contended for the title right out of the gate. At the 1959 British Grand Prix, the rookie tied Stirling Moss to set the fastest lap of the race. On December 12, at the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, McLaren became the youngest-ever Grand Prix winner at 22 years, 3 months, and 12 days of age. He’s still the sixth youngest, even in today’s era of racers hothouse-cultivated from toddlerhood. He went on to become a blue-chip talent throughout the 1960s, with 100 Grand Prix starts and four victories in F1. McLaren also won the highly controversial 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans, as depicted in the climax of the movie Ford v Ferrari, in which he was portrayed by Benjamin Rigby.

Yet none of that is what makes McLaren a legend. Some race car drivers are ruthless competitors. That was not McLaren. His brilliance was in developing cars and building winners.

In 1964, at the age of 27, McLaren built his first sports car, the M1A. It proved brutally fast in competition. McLaren also debuted his first Formula 1 car, the M2B at the 1966 Monaco Grand Prix. But the big news was the debut of the Mclaren M1B in the inaugural North American Can-Am series. The car was quicker around tracks then F1 cars of this era. In their trademark papaya orange paint, McLarens would so thoroughly dominate Can-Am over the next five seasons that the series became known as the Bruce and Denny Show, as McLaren and fellow Kiwi driver Denny Hulme claimed one checkered flag after the next. In the 1969 season, McLaren cars won eleven Can-Am races—every single one on the calendar.

A lot of guys could go out and win races in the 1960s, but few could develop cars from scratch and then drive them to victory like Bruce McLaren could. He possessed all the necessary qualities: engineering skill, patience, dedication, and natural talent.

“A racing car chassis is like a piano,” he once said of the development process. “You can make something that looks right, with all the wires the right length, the right size, and pretty close to the right settings. But until it is tuned, it won’t play so well.”

Aside from all that, McLaren possessed a kind of leadership skill that made winners of his team. He was so well-liked and respected, so courteous to those around him, and so lacking in ego that anyone who worked for him was determined to do their best.

In 1970, McLaren published the autobiography Bruce McLaren: From the Cockpit. Tragically, he penned his own epitaph in that book. “To do something well is so worthwhile that to die trying to do it better cannot be foolhardy,” he wrote. “It would be a waste of life to do nothing with one’s ability, for I feel that life is measured in achievement, not in years alone.”

On June 2, 1970, McLaren was testing a 220-mph Can-Am car at Goodwood. He was hammering down a straightaway when the engine exploded. The car essentially split in half. With no way to control the car, McLaren lost control and hit a concrete barrier. WItnesses say the fireball was over 30 feet high. McLaren was killed instantly.

He left behind a wife, a four-year-old daughter, an entire racing community, all shattered with grief. For some insight into how valuable and loved he was in the sport, consider a passage from his New York Times obituary.

“The death of Bruce McLaren last Tuesday diminishes all of us. This gentle, kindly man was more than a race driver, more than a car-builder. He was a friend to everyone in racing—in the pits, the stands, the business office, the motel lobby. Bruce didn’t go out of his way to make friends—he simply attracted them. As a team captain he worked as hard as his men… Always in the victory photo, that shy, incredulous smile, one so unprepossessing that even his rivals forgave Bruce for trouncing them. But as long as they had to be beaten, they might as well be beaten by the best.”

Unlike any 0f the driver-constructors of the 1960s, men like John Surtees, Dan Gurney, and Jack Brabham, Mclaren’s race team and the brand of cars that Bruce founded still exist today. As motorsport author Xavier Chimits has written, “It is Bruce McLaren’s finest victory.” McLaren cars have won the F1 world championship, the Indy 500, and the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Yet as much as his victories, the man himself and his warm smile must never be forgotten.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos