Phil Bredesen is a Democrat who thinks he can win in Tennessee. He might be right.

FRANKLIN, Tenn. — For Tennessee Republicans, Williamson County has long been considered the promised land — one of the reddest counties in what has increasingly become one of the reddest states in the country.

An affluent suburb south of Nashville, Williamson is idyllic, with quaint main streets and rolling green hills where some of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War took place. But in state politics, it is regarded as the land of surrender for Democrats, a county so firmly controlled by Republicans at every level that the other party often barely competes.

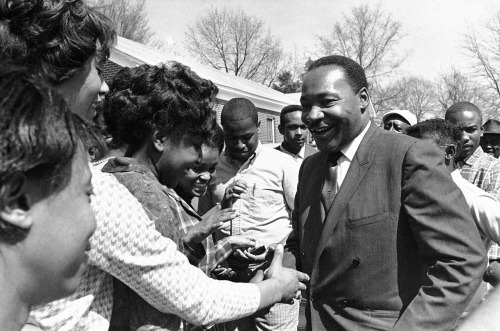

Just one Democrat has won here in the last 20 years — and as it happens, that candidate, former Gov. Phil Bredesen, was back in town on a recent Monday afternoon looking for votes. Nearly eight years after leaving the governor’s office, Bredesen, 74, recently emerged from political retirement to run for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Bob Corker, the moderate Republican and off-and-on critic of President Trump who announced last fall that he would not seek reelection.

Bredesen is not just any other Democrat in Tennessee. One of the most popular public officials in state history, the former Nashville mayor and businessman won two terms in the governor’s office and was the last Democrat to win a statewide election in this firmly red state thanks to a broad base of bipartisan support. His surprise decision to jump into the race in December put Tennessee’s Senate campaign on the national map, giving Democrats a slim chance at regaining control of the U.S. Senate this fall and an opportunity to reestablish a foothold in a region where the party has been largely wiped out.

But on the campaign trail the former governor rarely, if ever, mentions his own party affiliation. And he pointedly ignores questions about the national significance of the race. Unlike other Democrats this election year who have placed their opposition to Trump at the center of their campaign, Bredesen, a political centrist, has strenuously worked to avoid being cast as a member of the resistance. When Bredesen does mention the president, it is to declare, as he did in a recent campaign ad, that he is “not running against Donald Trump” but rather “to represent the people of Tennessee.”

Bredesen’s careful middle-of-the-road approach is a study in contrast with his likely opponent: U.S. Rep. Marsha Blackburn, a hard-charging, eight-term member of the House with one of the most conservative voting records in Washington.

A regular on the 24-hour cable news circuit, Blackburn, 65, has been one of Trump’s most passionate allies. And she has made that loyalty to the president front and center in her Senate bid, embracing him and his agenda in ways that other Republicans have not during this closely watched midterm election year. “People want to have a U.S. Senate that’s going to support the president,” Blackburn has said. “I will stand with President Trump.”

In a video announcing her Senate bid last fall, Blackburn, whose home district includes Williamson County, came out guns blazing, telling voters about the pistol she packs in her purse. She declared war on her own party, calling out Senate Republicans who “act like Democrats or worse,” and ticked off the ways she would support Trump’s agenda, including on immigration.

Describing herself as “hard-core” and “politically incorrect and proud of it,” Blackburn embraced her reputation as a conservative firebrand. “I know the left calls me a wingnut, or a knuckle-dragging conservative. And you know what? I say that’s all right, bring it on.”

In an equally fiery speech in late February to Williamson County Republicans, Blackburn, who still faces a likely primary challenge, blasted unnamed Democrats who would dare think they could try to win the Senate seat or any other race in this staunchly conservative state. “They think they can turn Tennessee blue. But they’re not even gonna turn it purple because they are running into the red wall, and the red wall starts right here in Williamson County,” Blackburn declared.

Bredesen’s visit to Williamson County came just a few days after Blackburn’s speech.

While he made no mention of his likely opponent, his stop seemed to be a quiet, but pointed effort to suggest that “red wall” she talked about wasn’t so impenetrable.

The former governor sat at a packed table of about a dozen people right in the front window of Puckett’s Grocery, a popular local eatery barely two blocks from Blackburn’s district office in downtown Franklin. The group included some prominent Republicans like Aubrey Preston, a developer and philanthropist from Franklin who has contributed tens of thousands of dollars to GOP candidates, including Blackburn. But he was also part of a “Republicans for Bredesen” group during the former governor’s last campaign. Bredesen filmed his campaign announcement video at Preston’s home.

The conversation focused on local issues like land preservation, a hot topic in this rapidly developing part of middle Tennessee. Meanwhile, Bredesen’s first ad had just launched on local television and on cable networks including Fox News. It featured Bredesen talking up his record as someone who had “worked across party lines … with Democrats and with Republicans” — bipartisanship he emphasized when talking to voters here.

A fiscal conservative known for his moderate approach and willingness to work with Republicans, Bredesen won his 2006 reelection race by a landslide, capturing 70 percent of the vote in what even then was a strongly red state. And in that race, he did what no other candidate had done before or since: He carried all 95 counties in the state — including Williamson County, a particularly surprising victory since that’s where his GOP opponent was from. “Even Jesus would have had a hard time carrying 95 counties” in Tennessee, Rep. Jim Cooper, a “Blue Dog” (moderate) Democrat whose district includes Nashville, joked at the time. But that was 12 years ago.

While early polls in the Senate race suggest voters remember and still like him, Bredesen faces a political landscape that is dramatically different than when he last ran for office. Elected Democrats have gone nearly extinct. And though the state had a long tradition of electing moderate lawmakers from both parties, pragmatic politicians like Bredesen have mostly retired or been voted out.

It raises the question of whether a candidate, even one as widely admired as Bredesen, can persuade voters in an era of unprecedented political polarization to look beyond party labels on Election Day.

The race is sure to have broad national implications, beyond the battle for control of the Senate, in which Democrats need to win just two additional seats to regain a majority. Tennessee’s race will help answer whether the electorate still wants lawmakers who can govern in the middle.

Bredesen says his gut tells him there are people like him who are tired of what he describes as “the super-hyperpartisanship” that has torn the country apart and left Washington at a standstill. Even so, he admits to polling to make sure he wasn’t embarking on a “suicide mission.” The results were promising enough to persuade him to jump into the race, but they didn’t suggest an easy path to victory. He readily admits this will be a harder race than any he has run before.

Not only will Bredesen have to win over a wide swath of Republicans across the state, including voters who voted for and continue to back Trump, he will have to do so while also energizing and holding support among Democrats who may be more conservative than in other states but still want to see a candidate who is willing to take on Trump more aggressively.

Still, the 74-year-old ex-governor, who had long resisted entreaties from Democrats to take on other campaigns over the years, felt an almost moral obligation to make the race. “No one can fix Washington,” he said, “unless you try.”

Bredesen never saw Trump coming. But he was less surprised than most when the former reality television star rode a populist wave of support from rural and working class voters into the White House in 2016. He had been warning his own party about losing ground among that electorate for years.

As governor, Bredesen had sensed resentment building among voters who felt left behind by both political parties. When the economy went south in 2008, in what would later be known as the Great Recession, the unemployment rate rose as high as 20 percent in some parts of Tennessee.

At the time, Bredesen reached out to lawmakers in Washington from both parties as they looked for answers. “I thought there was nobody in that town who had any idea what it was like for these people lying in bed at night and just seeing all these things that they had hoped for, for themselves, for their families, just sort of disappearing because of some crazy Wall Street banker somewhere,” he said.

Nobody, Bredesen said, seemed to truly grasp “the fear and frustration” felt by working-class Americans who have never fully recovered even as much of the rest of the nation has rebounded back. He has been particularly critical of his own party, describing Democrats as “tone-deaf” to voters in small-town America, who tend to be more culturally conservative and who turned out for Trump in droves.

“The Democrats, nationally, have done a great job of alienating a lot of voters with this kind of holier-than-thou superiority about a certain type of voter,” Bredesen said. “What was Hillary [Clinton]’s term? Oh yes, deplorables.”

Long before the era of Trump, Bredesen had been sounding the alarm for Democrats on the party’s messaging. In the summer of 2007, he appeared before the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), a group of party centrists who had gained influence during Bill Clinton’s presidency, where he said Dems desperately needed to find a way to reconnect with rural and blue-collar workers, especially in the South.

“If you asked me what the Republicans stand for, I could tell you in about 25 words: a traditional view of family, a central role for faith, low taxes, an assertive and combative view of American interests abroad,” Bredesen said at the time. He went on: “I challenge you to describe what the Democratic Party stands for in 25 words. You can’t do it. We’re just defining ourselves by what we’re not. We’re just criticizing the failure of others.”

History shows that the Democrats recaptured the White House in 2008, but the party continued to lose ground, and congressional representation, in states like Tennessee. Today, even the DLC no longer exists, having closed its doors in 2011.

Eleven years later, Bredesen offers a tight smile when asked about the speech and the suggestions he made to his party back then. “We didn’t do that, and Donald Trump is president,” he said matter-of-factly.

In a state where Trump won by 26 points, Bredesen is noticeably careful about how he talks about the president. He has repeatedly told reporters he does not want to be perceived as running against Trump — a line that eventually made it into a campaign ad in which the former governor, speaking to someone off camera, insists that he could find common ground with Trump and “separate the message from the messenger.”

“There’s a lot of things I don’t personally like about Donald Trump, but he’s the president of the United States, and if he has an idea and is pushing something that I think [is] good for the people of Tennessee, I’m going to be for it,” Bredesen declared in the campaign ad, a variation of what he often tells voters on the trail.

The ad did not mention any specific Trump policies, and Bredesen so far has not detailed areas of common ground between him and the president. He often pairs his Trump critiques to complaints about dysfunction in Washington in general.

“I don’t like the way this country and the way the media in this country has made everything about that person,” Bredesen said in an interview, referring to the president. “I think of Donald Trump more as a symptom than a first cause. And I think that symptom is that we as a party, … [and] a lot of Republicans too, have been tone-deaf to a lot of people who have been affected by globalization and technology and have got real concerns.”

Bredesen is quick to add that he doesn’t “have all the answers or solutions.” But in a subtle critique of Trump that is characteristic of his tone in the race, he added, “I think there are certainly better answers than demonizing every immigrant or starting trade wars or something like that.”

In some ways, Bredesen is an unlikely messenger for Red State Democrats. He’s not even from Tennessee. A Yankee transplant, he’s a native of Shortsville, N.Y., a small town 30 miles southeast of Rochester. While running for governor, he neutralized what could have been a liability in a state where rural voters are instinctively suspicious of outsiders by turning that detail of his biography into a plus. He explained to rural voters how he had grown up poor in a small town just like theirs. His father had left the family when he was a kid, so he and his mother, who worked as a bank teller, lived with his grandmother, who kept the family afloat by doing alterations and sewing.

But he went to Harvard (on a scholarship) and left rural New York for Boston in the mid-1960s. But Bredesen insists the mindset of a small town guy has shaped his years in public life. “While I live in an urban area now, I am basically a rural person,” he said.

Many of his relatives back in New York had voted for Trump and still support the president. “I don’t look at that as, ‘Well only racists or crazy people do that,’” he said. “I look at it as lots of reasonable people in this world are so estranged from what is happening in Washington that they want to see something different.”

A science whiz who was obsessed with space, Bredesen earned a degree in physics in 1967. After graduating he became a computer programmer, and after a brief stint in London moved to Nashville in 1975 with his wife, Andrea, a registered nurse who worked for a hospital management company. In 1980, working from a computer in his den, Bredesen founded HealthAmerica, a company that acquired and ran health management organizations. As he often tells voters, he went $10,000 into debt launching the company, but by the time he sold it in 1986, it was a $700 million a year company with 6,000 employees and traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

The sale made Bredesen rich. A financial disclosure form filed last week as part of his Senate campaign offered a broad view of his personal wealth. The former governor reported he held investment assets ranging in value between $88.9 million and $358 million between January 2017 and February 2018. And he reported income from $3.3 million to $20.1 million during the same period — an overall net worth that would make him one of the richest members of Congress if elected.

His strength as a candidate is that he doesn’t come across as a rich guy or an elite businessman. While he tends to do more listening than talking — once describing himself as “the strong silent type” — he is calm and measured, without being stuffy, and speaks the language of everyday Tennesseans.

Bredesen frequently mentions the “Walmart test” he has applied throughout his own career and has encouraged others in his party to adopt. In it, he imagines how a voter in Walmart might react if he tried to sell them on a policy. “I just imagine myself stopping a couple in the aisle of a Walmart in Winchester, Tenn., or someplace like that, and explaining to them what I was trying to do, and why and so on,” he explained. “If I could see them nodding their heads, they don’t need to agree or disagree, but if they were saying they could at least understand what I was trying to do, I felt like maybe I was on the right track.”

The former governor has also presented himself as an avid sportsman and a strong supporter of gun rights. During his first bid for governor, Bredesen scored political points when he took a sporting group up on its offer to demonstrate his trap shooting skills alongside his Republican opponent, who didn’t show up. The National Rifle Association gave him high ratings — until he vetoed a bill allowing guns in bars. “Alcohol and guns just shouldn’t mix,” he said at the time. His veto was overridden by the Republican-led state legislature.

While he still mentions his support for the Second Amendment, and wore a hunting vest for the video in which he announced his candidacy, Bredesen has more recently endorsed tougher gun laws, including stronger background checks. But he has stopped short of saying he wants to ban the kind of assault rifle used in the Parkland, Fla., attack. In a race likely to attract heavy spending from outside groups, that may be enough to keep the NRA from an all-out attack on Bredesen.

Public polling in the Senate race has been scant so far — and mostly from partisan sources — but all suggest a tight contest between Bredesen and Blackburn among likely voters heading into November.

Perhaps the best indicator of the closeness of the race came in recent weeks when word leaked that some Republicans, both in and out of Tennessee, were pressing Corker to reconsider his decision to retire. They reportedly voiced concerns Blackburn may be too conservative to win independents or could alienate mainstream Republicans, who have broken with their party to back Bredesen in the past. In February, Colleen Conway-Welch, the widow of Ted Welch, a major Republican donor, made headlines when she hosted a fundraiser for Bredesen.

Last month, Corker confirmed that he had considered reentering the race, but said he was sticking with retirement, though he declined to endorse Blackburn. He has said he should remain neutral ahead of the August primary. But some have wondered if he will endorse in the race at all because of his friendly relationship with Bredesen, who has known Corker, a former mayor of Chattanooga, for years.

The ex-governor says he spoke to Corker “numerous” times about the Senate race when he was still deciding whether he would run. He wanted to make sure Corker was really out of the race. And he quizzed him about what serving in the Senate is really like and whether he would enjoy it, telling reporters that Corker knows him well enough to gauge his “frustration” level. “We’ve been friends a long time,” Bredesen said.

There has some buzzing in GOP circles about the remote chance that Corker might endorse Bredesen over Blackburn — given he is more politically aligned with the centrist Democrat than the conservative Republican congresswoman. But a GOP consultant close to Corker, who declined to be named to speak more freely about the race, doubts that would happen. “More likely, he would just remain silent, but his silence would say everything to the Howard Baker wing of the party,” the consultant said, referring to the late Republican senator and former aide to Ronald Reagan who championed bipartisanism. Blackburn, he said, “will need real help there.”

In numbers that have been seized upon by Bredesen and his supporters, a recent Vanderbilt poll found that Tennessee voters tend to be more moderate than recent election results might suggest. According to the survey, about 62 percent of those polled said they regarded their fellow state residents as “conservative or very conservative.” But 48 percent said they viewed their own political leanings that way — a 14-point difference between perception and reality. Thirty-one percent of those surveyed described themselves as politically moderate.

Blackburn has one important ally: Trump, who has a 48 percent approval among Tennessee voters, according to the Vanderbilt poll — much higher than his average approval rating nationwide. But as in other parts of the country, Trump has lost ground in Tennessee. His approval was down 12 points compared to November 2016. In a potential warning sign for Blackburn and other Republicans here, the poll found just 35 percent surveyed felt Trump is changing Washington for the better, a 24-point drop since he was elected.

The same survey found little public thirst for some of the red meat issues that Trump championed during his first 14 months in office, including a crackdown on illegal immigration. Just 6 percent of those polled said the issue should be a top priority for Trump and Congress. Fifty-eight percent said illegal immigrants in the country should be allowed to stay and work, while 72 percent said they support allowing the children of illegal immigrants to be eligible for the in-state tuition rate at Tennessee colleges and universities — numbers that have increased since Trump was elected.

“It’s not clear to me that the right wing is still as strong in the state as some people think,” said John Geer, a Vanderbilt political scientist who helped oversee the poll. “They write letters, and they attend rallies, and they call their representative, but the state still has a strong pragmatic brand.”

Even many Republicans are skeptical Blackburn can go after Bredesen as a flaming liberal Democrat who would fall in lockstep with GOP boogeyman like House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. But she’s trying. Her campaign already regularly refers to the ex-governor as “the No. 1 recruit” of Sen. Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leader from New York and leading Trump critic who played a role in convincing Bredesen to join the race. Republicans argue that whether Bredesen is a moderate or not, he would be a reliable vote for the Democratic agenda.

But Bredesen dismisses the critique he would just be another Democratic foot soldier. “People know me,” he said. “I’ve got a good record of not being that way.”

He points back to his time as governor, when he worked with Republicans to balance the state budget. During that era, he made what he still describes as the most heart-wrenching decision he ever made as governor — trimming 200,000 people from the rolls of TennCare, the state’s Medicaid system for the elderly and the poor. It was a politically treacherous choice, but one later credited as saving the program.

His experience with TennCare and trying to figure out health care in the state later made him a leading critic of Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which he complained would put a huge fiscal strain on states. Though he reiterates that he does not support an outright repeal of Obamacare, Bredesen has said he is running in part to fix the law and plans to unveil a series of policies later this year aimed at bringing costs down and shoring up the plan — not unlike what he did with TennCare.

He knows that many lawmakers before him have headed to Washington with good intentions, only to get mired in the swamp. He frequently cites a Republican, Sen. John McCain of Arizona, as lawmaker he admires for trying to rise above politics and make deals, as the kind of senator he would like to be, but he doesn’t have “delusions” that things will be fixed overnight.

But in reemerging at this place and time, Bredesen also admits he “sure wouldn’t mind” showing Democrats how to win again with rural and blue-collar voters who used to be the party’s base. Few listened to him 11 years ago, but maybe they will now.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

- Ken Starr: Justice Department should evaluate claims by Stormy Daniels

- Advocates fear ICE is targeting immigrants who speak out

- Trump isn’t the first president to politicize the census

- While others march, these teens shoot. At targets.

- Photos: Central American migrants head to the U.S. border in annual Stations of the Cross caravan