Can New York achieve clean energy goals while protecting wildlife?

For bats, rock crevice roost sites across Central New York are prime habitat. It gives the animals the food and conditions they need to survive fall migration.

But, for a state racing to adopt renewable energy, the land is prime for something else: wind turbines. The benefit to farmland is its promise of deforested terrain with high-voltage transmission lines nearby.

Plus, energy collected upstate could speed to major metropolitan regions downstate, or so New Leaf Energy claims.

New Leaf – a renewable energy developer based out of Lowell, Mass., recently proposed that two 650-foot wind turbines be installed at 489 Sickler Road in Stark.

If implemented, the structures will be the largest in Herkimer County to date.

Locals voiced their concerns about habitat fragmentation and migratory bird fatalities as a result of the massive turbines.

“Animals need humans to solve climate change,” said Stark resident Rebecca Gretton. “But they also need places to live.”

Local agriculture

As stated by Dr. Winifred Frick, chief scientist at Bat Conservation International (BCI), while wind energy is an important part of the transition to a decarbonized energy infrastructure, wind turbines pose a major threat to bat populations. In the Global North - United States and Canada combined - nearly a million bats are killed each year from industrial wind projects, she confirmed.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) Public Information Officer Lori Severino highlighted the economic loss insinuated with species loss.

“Bats are insectivores and play a key role in stabilizing insects and other species of pests,” said Severino. “Here in New York they play a critical role in helping temper the impacts and outbreaks of gypsy moths and other common forest and agricultural pest species.”

Severino noted that bats don’t just play a crucial role in forest ecosystems; studies have shown that bats save the United States more than $3.7 billion each year given the role they play in agriculture.

According to Herkimer County officials, local agriculture generates $190,072,000 each year; $68,800,000 from crops alone.

In the Mohawk Valley, millions of dollars could be lost as a result of what Frick deems a “green-green dilemma.”

White nose syndrome

Some bat species are more vulnerable than others.

In New York, White Nose Syndrome (WNS) is responsible for more than 90 percent of observed declines in cave bats, with the Indiana, little brown, northern long-eared and tricolored bats the species most affected. WNS is now present in most states and portions of Canada, resulting in the recent listing of the northern long-eared bat as endangered (the Indiana bat has been a listed species since the 1980s).

“Species impacted by WNS and wind turbine interference are the most at risk,” emphasized Frick. “This tends to be long distance migratory species like the hooray bats, eastern red bats, silver-haired bats, and tricolored bats. These animals, susceptible to both stressors, will likely become endangered if regulations aren’t enforced.”

The DEC requires post-construction bat mortality studies from all wind projects.

“That’s how we estimate general impacts,” said Severino.

In fact, the state recently developed an index in tree bat population trends by initiating mobile acoustic surveys that record bat calls along roadsides during summer evenings. Severino boasted that the “groundbreaking methodology” is now being adopted by other states as part of the developing Northern American Bat Monitoring Protocol.

Still, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Associate Professor Dr. Vanessa Rojas called the outlook “grim.” She pointed to a wind farm in Maple Ridge NY where estimated fatalities (in bats per megawatt each year) was 14.9.

“The data is substantial enough for us to be fearful about precipitous population decline over the next few decades,” said Rojas.

Intrinsic value

Frick went on to outline the many benefits to bats, aside from their billion-dollar economic value.

“Sure, bats save farmers money by eating pests that cause crop damage,” said Frick. “But, they also – more commonly overlooked – reduce the amount of pesticides sprayed on our food which has implicit health benefits.”

Apart from the myriad of studies conducted in the U.S., Frick pointed to global studies that measure bats' impact on cotton production in Australia, rice harvesting in Thailand, and cacao extraction in the Neotropics. In Thailand, she explained, researchers estimate the presence of bats facilitates the harvest of enough rice to feed 20,000 people.

“We share this planet with other animals,” continued Frick. “It's incumbent on us to protect our biodiversity; it’s our heritage. Bats provide essential ecosystem services and connect us to the wonder of nature. Their intrinsic value is comparable to their financial value.”

As mentioned by Frick, immunologists often look to the genomes of bats when developing medical therapeutics – they’ve “contributed to solutions for the betterment of mankind.”

“Plus, bats inspire arts and entertainment,” laughed Frick. “Without bats you can’t have Batman, right?”

Green-green dilemma

In April, Frick contributed to a new study published in Bioscience which called for a global response to the “green-green dilemma” between wind energy production and bat conservation.

“Mobilization can and should be ignited at the local level,” said Frick. “The encouraging thing is there are solutions. We know that if we change what’s called the cut-in speed – the speed at which we allow turbine blades to spin – to five meters per second or higher we can dramatically reduce the number of bats killed.”

The cut-in speed only needs to be tweaked from dusk to dawn during migratory periods, added Frick. She said that curtailment would only result in a 4% loss in energy while reducing bat fatality over 50 percent.

“Regulatory implementation is needed because wind companies don’t have a market incentive to make those adjustments themselves,” explained Frick. “That's where local government comes into play. We must create ways for developers to operate in a sustainable way that doesn’t put them at an economic disadvantage.”

Frick acknowledged mobilization efforts in Alameda County, CA. The government passed a law curtailing the operation of cut-in speed at wind facilities. Their goal? To generate wind power without contributing to biodiversity loss, she said.

“The green-green dilemma is not an anti-wind tactic,” said Frick. “We need renewable sources in our fight against climate change. But we must harness energy in a way that meets its promise to help the planet. We don’t need to choose between wind energy or bats; we can have both.”

BCI has an active research program continuing to examine ways to reduce bat fatalities while increasing power generation.

In the meantime they are pushing to standardize four standard regulations:

Siting wind energy away from hibernacula with high abundance and/or diversity of bats.

Feather turbine blades below the manufacturer’s cut-in speed from dusk to dawn all the times of the year bats are active.

Curtail turbines below at least 5.0 m/s wind speeds at night during periods of high risk.

Standardize data collection and reporting across states and provinces, including open data accessibility.

Call to action

Concerned resident Marie Armstrong traced the start of industrial wind projects in Stark back to 2019, when town supervisor Richard Bronner signed the transmission line paperwork.

“Last year they started signing leases with land owners for the project,” said Armstong. “More than 45 farmers across the towns of Stark, Warren, Danube, and Springfield have already leased their property.”

Local pushback has manifested in the form of groups like No Big Wind and Conserve Our Agricultural Heritage (COACH) which encourage farmers not to lease their land, thus halting “intrusive” projects from the get-go.

For financial reasons Armstrong pointed out that saying no can be a lot harder than it seems. Still, she emphasized its importance.

Armstrong highlighted that New Leaf’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) includes an entire section admitting the project’s impact to wildlife.

“The project may have moderate to large impacts on animal species,” the document states. “The site may contain potential breeding and/or forging habitat for state-listed threatened avian species, the northern harrier and upland sandpiper. The turbines, when in operation, may have a moderate to large impact on migrating birds. Bat populations would also likely be impacted.”

Protecting the 'marvelous normal'

As a retired Audubon specialist, Gretton voiced her anxieties about the wind turbines.

She clarified the common misconception that birds fly low when they’re migrating.

"Having watched the birds in this region for decades I can confirm that our bat species do fly high when they migrate,” said Gretton. “They will be intercepted by these massive industrial wind blades which will be detrimental for the remaining population that still exists.”

Gretton used to have bats living behind the shutters of her house, but not anymore.

“My neighbors have a beautiful barn and sometimes I’ll still see a few bats flying from their rafters,” smiled Gretton. “It’s joyful to see them again … to hear their little shrieks. But it’s also heartbreaking to know they’re at risk because of this new project.”

Bats aren’t the only species in danger.

According to Gretton, this spring the song sparrow, field sparrow, savannah sparrow and baba lynx will be nesting in the grassland. So will the eastern meadowlark, black birds, red tailed hawks and bald eagles.

“Northern Harrier and short eared owls have finally returned to this land and to imagine them offset again is gut wrenching,” sighed Gretton. “Our locals work hard to preserve this habitat and raise multigenerational families that do the same. They respect their wells and this land. They may not be paying attention to all of the birds around them but it's part of their white noise. It is their marvelous normal and the loss will be felt by all.”

Grassroots advocacy

On March 30 Armstrong and Gretton went bird watching.

Together, they counted eight bald eagles, four northern harriers, five woodland ducks, three American kestrels, three Canadian geese, one blue heron, and three red-tailed hawks (as well as multiple turkey vultures, red-winged black birds, robins, crows, and pigeons).

“Protecting all animals – not just bats – is crucial,” said Gretton. “By applying conservation methods and raising awareness hopefully we can preserve the species that still remain.”

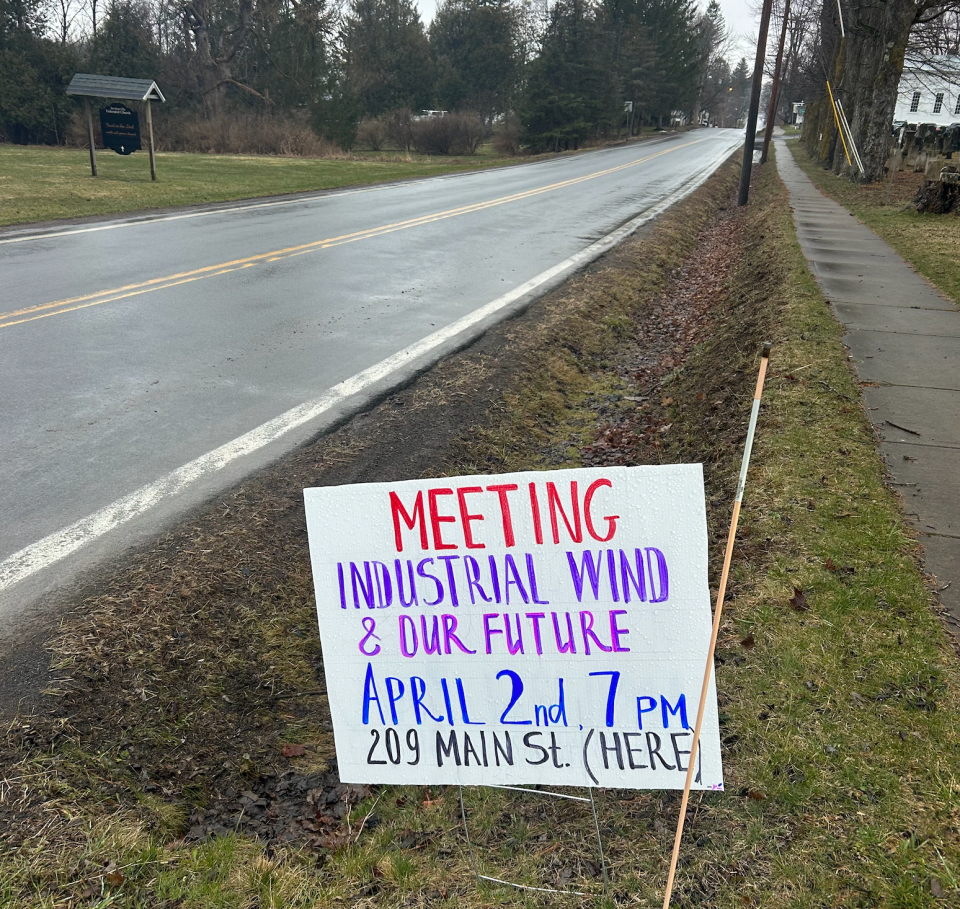

The town of Stark is developing a nine-month moratorium for all new windmill projects. Officials have urged local residents to join in on the legislative process.

Although amendments would not apply to the New Leaf projects on the table, there is an opportunity to enforce operational regulations, rezoning laws, and a new comprehensive plan for future proposals, said Armstrong.

The open meeting is at 7 p.m. April 30 at the Owen D. Young Central School in Van Hornesville.

“Your vote matters,” Frick assured. “Grassroots advocacy is as important as global rehabilitation. This is where it all starts.”

This article originally appeared on Observer-Dispatch: Building wind power in New York responsibly and ecologically