NC receives ‘D’ grade from group monitoring protections for live organ transplant donors

It comes naturally to pour your heart into the people you love. In North Carolina, giving them a lifesaving organ such as a kidney or part of a liver can prove much more of a challenge.

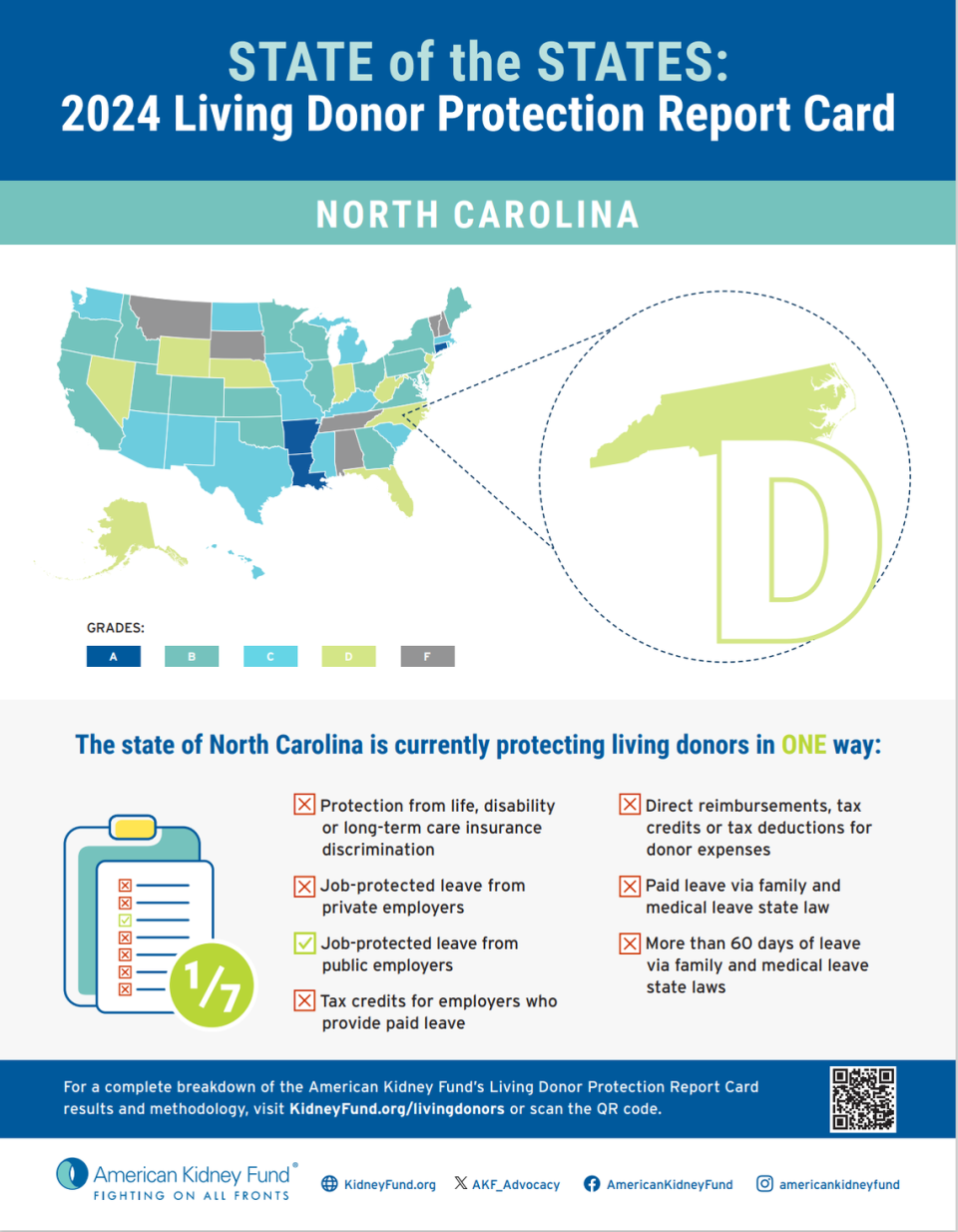

The state got a “D” grade on this year’s Living Donor Protection Report Card, a review by the National Kidney Fund. It ranks states based on their implementation of laws that encourage living organ donation and protect donors from potential costs such as lost wages and insurance discrimination.

Living organ donation is the gift of an organ — most often a kidney — from a living, healthy donor to a recipient whose life, or quality of life, depends on it.

North Carolina and eight other states got the National Kidney Fund’s “D” grade because they have only one of seven categories of legal protections in place. Six states got “F’s” for having zero legal protections.

Why do living organ donors need protection?

Across the country, 101,000 people are on the waiting list for a kidney, but only 17,000 patients receive one each year, according to the National Kidney Foundation. Every day, the organization says, 12 people die waiting for a kidney.

In North Carolina, 3,674 people in North Carolina were waiting for a kidney transplant as of March 14, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. Some wait for years, and some have to undergo dialysis several times a week while they wait.

Of those who do get a transplant, 75% to 80% will receive the organ from a deceased donor.

Advocates say many more kidney patients could be saved through living organ donations, because:

▪ The pool of living donors who could be matched to kidney patients is larger than the supply of organs available through deceased donors, meaning patients could get transplants sooner. Some could get a transplant before they need to go on dialysis.

▪ Organs from living donors begin to work faster after they’re transplanted than organs from deceased donors.

▪ Organs from living donors typically work longer than ones from deceased donors.

Many people don’t realize they can live a normal life with only one kidney or that they can spare a section of their liver, a lung lobe or a section of intestine.

And while the medical expenses of being a living organ donor are covered by insurance or by transplant programs such as the National Kidney Registry, without legal protections, living organ donors worry about other costs such as missed work.

“Living donors are the most unselfish, loving people you’re ever going to meet,” said Gayle Vranic, a transplant nephrologist who leads the living donor kidney transplant program at Duke Health.

“And someone who has made the heroic decision to give an organ to someone else should not be rewarded for making that lifesaving decision with a bill. It only makes sense to remove financial barriers for folks.”

What living donor protection does NC have?

Only one: State employees may be given up to 30 days paid leave to donate an organ.

What living donor protections does NC need?

Advocates have repeatedly proposed “living donor protection acts” to the N.C. state legislature and to Congress, neither of which has approved them.

In addition to paid time off for public employees, proposed legislation includes:

▪ Prohibiting life, disability and long-term care insurance companies from denying coverage or charging higher premiums to living organ donors.

▪ Requiring private employers to protect the jobs of people who take time off to donate an organ.

▪ Tax credits for private employers willing to provide paid leave to workers who donate an organ.

▪ Direct reimbursements, tax credits or tax deductions to cover donor expenses.

▪ Paid leave for donors via family and medical leave laws.

▪ More than 60 days of paid leave for organ donation when needed.

Almost anyone can get kidney disease

The American Kidney Fund says the number of people in North Carolina living with kidney failure has increased by more than 35% since 2009. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, kidney disease is the 9th leading cause of death in the state, in part because diabetes and hypertension, which contribute to kidney failure, are widespread in North Carolina.

About 1.7 million North Carolina residents have kidney disease, and it’s most prevalent among the poor and in rural areas of the state.

Paul Offen didn’t have diabetes, hypertension or any other known risk factors when he went to see a doctor during his senior year at N.C. State University in 2004. He had been fighting a stubborn strep infection, and when he had some blood work done, it showed he had developed kidney disease, which the doctor blamed on the strep.

His mother, Carol Offen of Carrboro, remembers being shocked by the news but said the doctor reassured Paul and her that with monitoring, Paul likely would have at least 20 years before the disease progressed.

“But then a couple of months after he graduated, he went for his lab work and they said, ‘Oh, my God, your kidneys are failing,” she said.

He would need to go on dialysis within months, doctors said, and ultimately would need a transplant.

The whole family immediately explored living donor options. At 14, Paul’s sister was too young at the time to be eligible. His father had previous medical issues that disqualified him. Carol Offen became her son’s best hope.

But Paul had aged out of his mother’s health insurance coverage, and with his kidneys failing, couldn’t work full time and qualify for employer-based insurance of his own.

It took two years of working part time to gain enough credits for Medicare to pay for a kidney transplant for Paul, his mother said, which he had to do while spending three days a week going to dialysis to mechanically flush the toxins from his system.

“It was awful,” Carol Offen said.

Meanwhile, until the transplant center knew how the bills would be paid, Carol couldn’t begin testing to make sure she would be a good living donor match.

Finally, in 2006, Paul qualified for the coverage and his mother proved to be a match. Her employer at the time, RTI International in Research Triangle Park, allowed her coworkers to donate sick time to cover the additional leave she needed.

Offen, who’s now retired, knows other living donors aren’t as lucky, so she advocates for living donors in front of lawmakers and anyone else who will listen. She co-wrote a book describing what living donors can expect from the experience.

“I’m a wimp,” she says. “I’m not a dare-devil. I was so thrilled when it was over. But I mean, it was much easier than I expected and even more gratifying than I expected. I knew that I was going to be thrilled at the benefit for my son, and that was the most important thing.

“But I had no idea how gratifying it was going to be for me personally.”

Today, both Carol and her son are thriving. At 75, she’s busy, does Zumba twice a week and feels great.

“I like to say that both of my kidneys are doing well,” she said. “But I could apply for life insurance or long-term care insurance tomorrow and be turned down or overcharged just for the fact that I have only one kidney. That’s because of misinformation.”

Advocates call for grassroots support

Holly Bode, vice president of government affairs for the American Kidney Fund, said passage of a federal Living Donor Protection Act, proposed again last year, would bring all states up to at least a “C” on the organization’s grading scale.

State bills potentially could provide more protections.

Either is more likely to pass with grassroots support, Bode said.

Interested in becoming a living organ donor?

If you’re interested in becoming a living organ donor, information is available through the transplant centers at Duke Health, UNC Hospitals and Charlotte’s Carolinas Medical Center.