How Wake schools aim to ‘be as ready as we can be’ when opioid overdoses happen

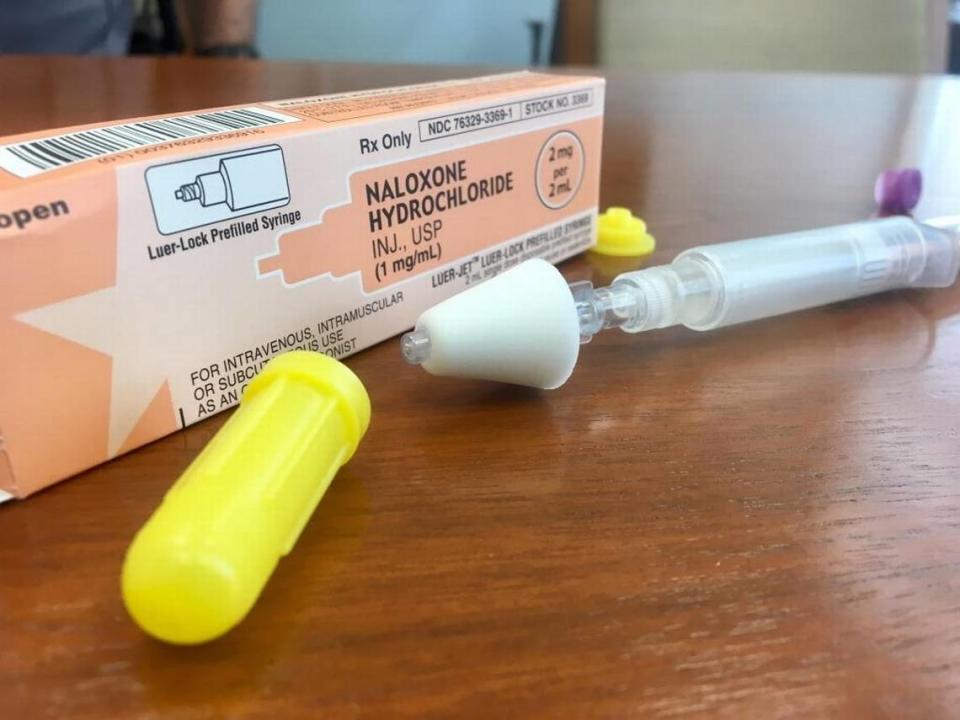

Wake County schools could soon be stocked with Naloxone to treat potential opioid overdoses on campus.

The school board’s policy committee recommended on Tuesday new rules on emergency use of Naloxone. The policy requires schools to train people in how to administer Naloxone and directs Superintendent Robert Taylor to develop a program to place Naloxone at schools, early learning centers and district administrative offices.

“This is fantastic,” said school board member Sam Hershey. “This warms my heart we’re going in this direction. I think it’s crucial. At some point it’s going to hit, and we’ve got to be as ready as we can be.”

The policy, which will go the full board for its approval, comes as opioid overdoses and addiction have surged nationally.

In 2022, 219 people died from drug overdoses in Wake County, The News & Observer previously reported. Opioids, medicines prescribed for pain like codeine, fentanyl, oxycodone and morphine were responsible in three-quarters of the deaths.

Naloxone used 21 times in NC schools

Naloxone, which is the generic name for Narcan, can reverse an opioid overdose when given in time.

Currently, the only people in Wake schools who carry Naloxone are school resource officers.

According to an earlier Wake presentation, there have been no cases of Nalaxone used in district schools. But Naloxone was used 21 times during the 2022-23 school year for suspected overdoses on other North Carolina school grounds.

“Nobody is safe from it, no matter where you are,” said board member Cheryl Caulfield. “Maybe it hasn’t hit in our schools, but better to be safe than sorry.”

The Wake policy doesn’t require Naloxone to be available at activities held off school grounds, such as field trips or off-site athletic events. The policy also wouldn’t guarantee availability of Naloxone at schools.

Stocking schools with Naloxone

The district estimates that it could cost $6,500 to $30,000 to place two Naloxone doses at each school. Hershey has suggested funding the Naloxone by eliminating a proposed cut in the high school student parking fee.

Taylor said he’s talked with the county health director about getting Naloxone in schools.

“They are ready and willing to partner to make sure that we have Naloxone on hand,” Taylor told the board.

The Wake County Board of Commissioners recently approved a plan to use $300,000 next year toward expanding access to Naloxone. It’s part of the $65.6 million that Wake County will get over the next 18 years from a historic national opioid settlement.

The settlement comes from companies that made or distributed prescription painkillers and were sued for their role in the millions of people who overdosed on opioids or became addicted. North Carolina will be getting $1.5 billion.

Increasing awareness of opioid overdose symptoms

The policy committee revised the rules on Tuesday to say at least three people should be trained at each school to administer Naloxone. The original policy had only said one or more person at each school should be trained.

The change came after staff said it would take about 15 to 20 minutes to train people on how to administer the drug.

“Sadly this is something that more and more folks are feeling in their personal lives, whether it’s up close and personal or within the community,” said board member Lindsay Mahaffey, who chairs the policy committee.

Board members said it’s important for as many people as possible to know the signs of opioid overdose and how to provide treatment. Board member Toshiba Rice cited the case of how her 25-year-old son died after taking a fake prescription pill that was laced with a deadly drug.

“Sometimes students will take a pill that they think is OK from someone else, and it’s really not,” Rice said.