Election officials in the US are under threat. A key county just faced a major test ahead of November

Everyone seemed determined not to jinx it.

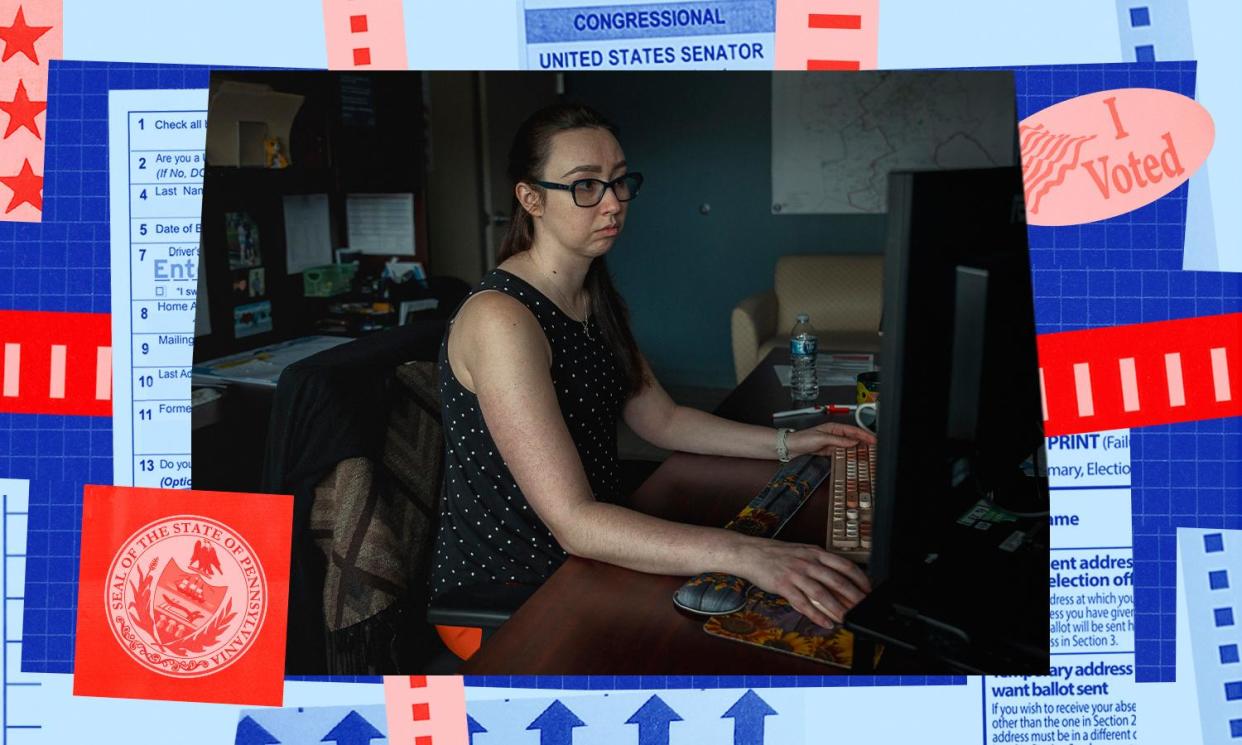

Jim Rose, the director of administrative services in Luzerne county in north-eastern Pennsylvania, had been listening to the radio all morning and had not heard “a single peep” about problems at the polls during Pennsylvania’s primary on Tuesday. When he ran into Emily Cook, the county’s acting director of elections, she wasn’t ready to celebrate. It was, after all, only mid-afternoon, and the polls would be open until 8pm.

Related: Exclusive: Georgia lawmaker runs secret election-conspiracy Telegram channel

“If you say that, you have to go outside, spin around on your left foot – it has to be your left foot – and throw some salt,” she said.

She may have only been half-joking. Cook had reason to be superstitious. While the political significance of Pennsylvania’s primary on Tuesday was somewhat low, the stakes were extremely high. Luzerne county has had a number of high-profile errors in running its elections in recent years, including when multiple precincts ran out of paper in 2022 and ballots were found discarded in the trash in 2020.

It has also had extremely high turnover. Cook, 26, is the seventh person to lead the election office since the fall of 2019. Previously the deputy director, she took over the position about two months ago.

“I am very conscious of how important it is that I get this right, not just for the department or the county on the whole, but for my own job,” she said in her office. “It feels like a test and preparation for what comes in November.”

Election day is a thankless task for Cook and the thousands of other officials charged with the nuts and bolts of administering voting across the US. In a best-case scenario, they are invisible – everything goes smoothly and no one notices the incredibly delicate ballet of details that need to take place to pull off a successful election.

But human errors take place all the time, and have increasingly sparked a cascade of wider conspiracy theories. Since the 2020 election, when Donald Trump spread baseless lies about the election, a flood of officials have left the profession, prompting concerns about the widespread loss of institutional knowledge.

On Tuesday, Cook had been up since 4am and was responsible for everything from making sure there was enough pizza for employees in the office to fielding reports of issues at the polls. In the span of about an hour and a half, she spoke to a woman who wanted to report what she believed was voter intimidation, talked to an election judge at the polls about some electioneering that may have been getting too rowdy, conducted two television interviews with local reporters, huddled with county lawyers, and made sure dinner was ordered for that evening.

There were a few minor issues. There were some aggressive people electioneering for candidates. A small number of voters were told to come back to a polling location when there was an issue with a ballot marking device (they should have been offered an emergency ballot). Someone had placed small flyers of Donald Trump inside a polling machine at one precinct and Cook and another employee were working to get them taken down.

En route to one of her interviews, Cook ran into Denise Williams, the chair of the county board of elections, who asked her if she had heard reports that there wasn’t space for a write-in candidate in one of the races. Cook said she would look into it.

But these hiccups are somewhat typical in elections and were far from the major issues Luzerne county has faced in the past. By the afternoon, Cook was especially pleased that the county hadn’t had to go to court to petition to extend voting hours – something that happens when there are major issues at the polls.

“Never calm, but I’ve definitely seen it more chaotic,” she said. “I think that’s the best we can hope for.”

Cook was appointed the acting director on 12 February, giving her a relatively short runway until the primary. She had worked in the election office since 2019 – experience that she drew on as she quickly took over for election day.

Still, there have been leadership and management lessons she’s learned.

“I don’t like to tell people no. I like to find a solution,” she said. “I think that’s part of what burns people out here, trying to keep everyone happy. Because everyone wants something completely different.”

One floor above Cook’s office, Romilda Crocamo, the county manager, was also knocking on wood all afternoon. “I’m trying not to jinx it,” she said. “No earthquakes, no sinkholes.”

For election day, she wore shoes with the American flag on them and a blue sweatshirt with the word Vote written across it in red. She had arranged for employees in the election office to get the same sweater (Cook and at least one other staffer was wearing the same one). Crocamo, who was also wearing an Avengers-themed lanyard, loves election day, and she confessed that sometimes she wonders if she’s too over the top.

Every year around election times, the county needs to recruit employees from other departments to go and help staff the election office.

“Historically, people are like ‘I don’t like elections’ – it’s like you’re condemning them to hell,” she said. But this time around she noticed that something had changed. “This time we had so many people who were like … ‘I wanna help.’”

Cook agreed there had been a change in the election office after the negative attention the office has received.

“There has been a culture change [of] ‘OK, we’re all gonna make this work together.’”