University of Oregon researchers discover giant prehistoric salmon had fangs

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) – New research, with help from the University of Oregon, has found that the largest salmon to ever live about five million years ago had fangs.

According to the researchers, the giant prehistoric salmon — Oncorhynchus rastrosus — had a pair of fangs protruding from the side of its skull instead of downward pointing teeth that scientists previously thought they had.

The discovery, researchers note, can help scientists have a better understanding of modern ecosystems.

2 Oregon towns have some of the dirtiest air in the U.S., new report finds

“I’m delighted that we have been able to put a new face on the giant spike-tooth salmon, bringing knowledge from the field in Oregon to the world,” said Edward Davis, an associate professor of earth sciences at the University of Oregon and director of the Condon Fossil Collection at the UO’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

“This project highlights the international scope of collaborations at the UO and Museum of Natural and Cultural History,” Davis said, “as well as illustrating the way local Oregon discoveries can have implications for understanding evolution and the consequences of climate change on the global scale.”

On average, the salmon grew to more than eight and a half feet long and were the largest and lived in Pacific Northwest waterways more than five million years ago, the researchers said.

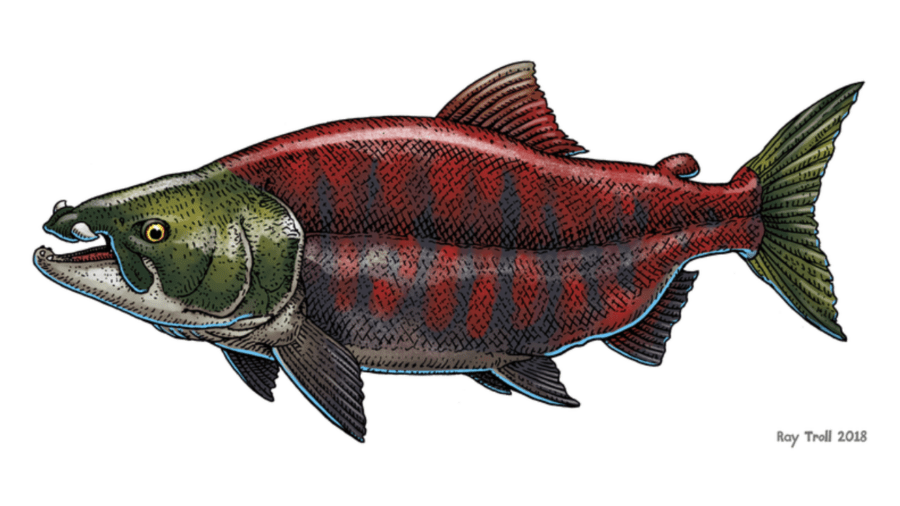

A fossil of a spike-tooth salmon was the subject of new research from the University of Oregon which found that the giant prehistoric salmon had fangs, after paleontologists previously thought the fish had saber teeth (Courtesy University of Oregon.) New research from the University of Oregon found that the prehistoric spike tooth salmon – which grew about 8.5 feet long, had fangs. Paleoartist Ray Troll demonstrated how big the fish grew in a sketch (Courtesy Rich Grost.)

In comparison, researchers noted the modern Chinook salmon tops out around five feet and the Siberian salmon is now the world’s largest salmon, which can grow to six feet.

Paleontologists originally found a prehistoric salmon fossil in the 1970s and noticed it had two large teeth on the upper jaw. However the fossil was crushed, and the upper jaw bones were disconnected from the rest of the skull, the University of Oregon said.

Based on that discovery, paleontologists initially thought the two fangs pointed downward, similar to a saber-tooth cat, and named the fish “saber-tooth salmon.”

Oregon hotel named among best beach resorts in the U.S.

In 2014, paleontologists uncovered additional O. rastrosus fossils in the Gateway Quarry in Jefferson County, Oregon which were better preserved, revealing the saber tooth more closely resembled spikes.

“We have known since the 1970s that these extinct salmon from Central Oregon were the largest members to ever live,” said Kerin Claeson, lead author and professor of anatomy at Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. “However, more than a half a century later, new discoveries told us that these were probably not ‘gentle giants’ on account of massive spikes at the tip of their snouts.”

Researchers believe the spikes were about two inches long, slightly curved, and could have been used as a weapon when the salmon swam upstream to spawn.

A model of the spike-tooth salmon by paleoartist Gary Staab is on display at the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History (Courtesy University of Oregon.) An illustration of the spike-tooth salmon by Ray Troll, showcasing the prehistoric salmon’s fangs – a new discovery made with help from the University of Oregon (Courtesy Ray Troll.)

“Along the way the spikes would have been useful to defend against predators, compete against other salmon, ultimately build the nests where they would incubate their eggs, and then fight off any rival salmon who wanted to use their nests instead,” Claeson said.

The researchers also found the front of the skull where the upper jawbones attach comes to a sharper point in males compared to females.

“However, we stress that females and males alike possessed the enormous, tusk-like teeth,” said Brian Sidlauskas, a professor and curator of fishes at Oregon State University and a co-author of the paper. “Therefore, the sexes were equally fearsome.”

Portland State University study finds village, motel homeless shelters have better outcomes

Researchers said the discovery can provide insight into ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest.

“These majestic animals went extinct with cooling oceans millions of years ago,” said Davis. “And their biology tells us about the habitats we might see in the next hundred years if global climate change goes unchecked and brings us back to the warm oceans of the heyday of the giant spike-tooth salmon.”

The new research – conducted by UO’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History, Oregon State University, and Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine – was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KOIN.com.