Surviving Bataan: Fayetteville area prisoner of war connections

In 1988, Congress approved designating April 9 as Former Prisoners of War Day.

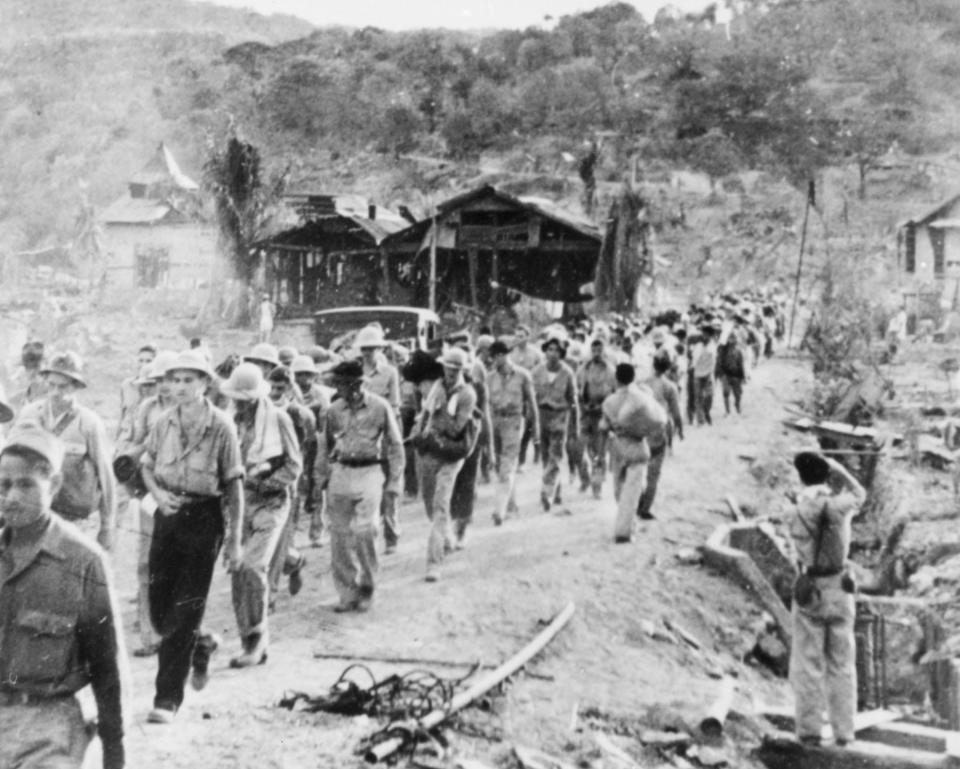

The day commemorates the April 9, 1942, surrender of more than 12,000 American troops and 66,000 Filipino soldiers on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines to the Japanese.

Afterward, prisoners were forced on a 65-mile march, later known as the Bataan Death March, from the peninsula to a prisoner-of-war camp that resulted in thousands of deaths along the way, while there were several thousand more losses in the camps until American and Filipino forces liberated survivors in 1945.

While then-Fort Bragg units were deployed elsewhere during World War II, some American service members held in the Japanese POW camp had ties to the local area.

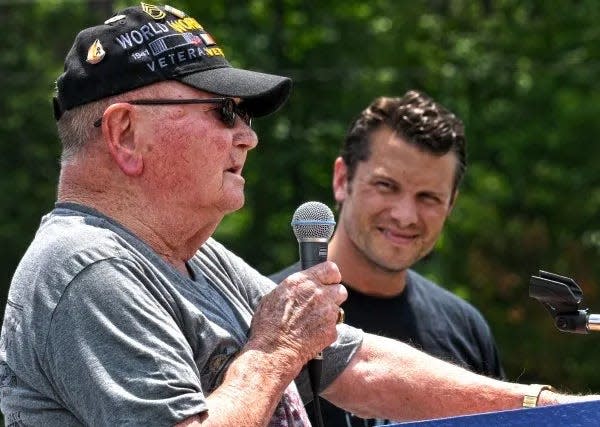

Here’s a look at local veterans who spoke with The Fayetteville Observer in the past about their time as a prisoner of war.

Col. Stuart Wood

The effects of being a prisoner of war lingered with retired Col. Stuart Wood 45 years later.

According to an August 1993 obituary for Wood, he was an intelligence officer, who was held as a prisoner of war by the Japanese from 1942 to 1945, first in the Philippines and later in Manchuria.

Wood said in April 1990 that he still had nightmares about Japanese captors suddenly screaming, slapping, kicking and killing him.

"There's just no excuse for the cruelty they showed to a bunch of starving men," said Wood, who lived in Fayetteville. “They'd knock your block off for no reason at all, or worse they'd make you do things like (hold) buckets full of water with your arms outstretched. When your arms came down, they'd poke you in the butt with a bayonet.”

Wood said he was spared the Bataan Death March, because an American military evacuation plane took him off the island before the Japanese took control.

The evacuation plane struck a rock on April 30, 1942, while attempting to take off from the island of Mindanao, leaving the passengers stranded 550 miles south of the besieged Philippine island of Corregidor.

A second plane was dispatched, but it got lost in a storm and eventually crashed in the ocean, Wood said.

Japanese forces soon showed up with orders to haul Wood back to Manila for questioning about American operatives in Japan, he said.

Wood said he recognized one of the inquisitors as a Japanese soldier he shared cigarettes with during a two-year stint as a language exchange student in Japan.

"It might have saved my life,” Wood said. “Life was tenuous at that point. They'd shoot you for no reason."

Taken to a prison camp, Wood said he spent the next three years in captivity, being moved from camp to camp, some of which were staffed by Japanese Imperial Army rejects.

"We had guards that weren't good enough to make it in the regular army, and they were the cruel ones," he said.

The war ended for Wood in September 1945 when Russian troops liberated the Manchurian prison camp, he said.

Following the war, Wood was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division at then-Fort Bragg. He retired after 30 years of service.

Afterward, he settled in Fayetteville and became coordinator of the Cumberland County Area Civil Defense.

Curtis Stevens

Curtis Stevens was another Fayetteville resident who was a prisoner. He spent three years, four months and nine days in captivity, according to an April 1994 Observer article.

Stevens was a Navy petty officer second class helping protect the beaches of Corregidor when he was captured in May 1942.

He remained in the Navy, retiring as a chief petty officer in 1958 and serving another 10 years in the Reserves.

He’d later become a commander of a chapter of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor that includes North Carolina and several other states.

The group was instrumental in getting April 9 named National Former POW Recognition Day.

Brig Gen. Edward King

According to a May 2001 article, Brig. Gen. Edward P. King was also a survivor.

King was commander of American troops in Bataan when he surrendered April 9, 1942.

King was also responsible as a young officer during World War I for surveying local land for a new artillery post in the North Carolina Sandhills that’d later be known as Camp Bragg, Fort Bragg and now Fort Liberty.

Jesus Rabano

Serving under King was Jesus Rabano, a soldier in the Filipino Scouts who survived the Bataan Death March.

Rabano would come to the U.S. after the war, serve at then-Fort Bragg, retire as a master sergeant and work several more years as a civilian employee on post. He was also a leader in Fayetteville’s Filipino community.

Rabano told the Observer in 2005 that he remembered the beheadings and the Japanese giving men shovels to dig their own graves.

After his March 2012 death, his widow Florinda Rabano said her husband told her that during the 60-mile march, Japanese troops would randomly pick one of the soldiers and make him dig his own grave. They would then blindfold soldiers, make him kneel and cut off his head, she said.

Rabano told his wife the soldiers were only given a ball of rice and a canteen of water for the trip. He believed he survived because he did not eat and drink it all immediately, she said.

Rabano was released from a POW camp when the Philippines was liberated in 1943.

John Leroy Mims

Aberdeen resident John Leroy Mims was 18 years old when he fought the Japanese in the Philippines, according to a November 2001 article.

Mims first tried to join the Army at 13 when he needed a job after his parents died but was kicked out and went back in at 16, with the Army sending him to the Philippines in 1941.

He was part of an American and Philippine force that defended the islands against heavy Japanese attacks following Pearl Harbor, but the troops soon ran low on food and other supplies.

Mims said the soldiers fought the Japanese in Manila and Corregidor, an island off the Bataan Peninsula.

He became a prisoner of war after American forces surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942.

"We used to think that we were disgraced because we were prisoners of war, but we were ordered to surrender," Mims said. "We were without ammunition, without food, no medical supplies. After the fifth time I was wounded I stopped counting."

Mims endured the Bataan Death March, with the Japanese forcing American and Philippine forces to march with little water and food from Bataan through the Philippine jungle to a prison camp more than 60 miles away.

While others died from disease, hunger or Japanese bullets and bayonets, Mims survived but was forced to work in rice paddy fields and coal mines.

In April 2003, Mims said Japanese soldiers hit him with sticks and rifle butts. Somebody smashed a Coke bottle into his face, breaking his teeth.

He remained a prisoner of war until 1945.

"I was the first one in camp to know the war was over,'' he said. "I heard the Japanese talking on the other side of the fence at night when they thought I was asleep.”

Mims said he didn’t reach American troops until the end of September 1945.

He stayed in the military for another 18 years before retiring in 1963 as a master sergeant.

He said his physical condition from being a POW held him back from promotions.

In the three years he was held captive, Mims said in 2003, his neck was broken in three places and vertebrae in his spine fused together.

According to a November 2016 obituary, Mims died at the age of 94.

Other local connections

Other POWs with local connections according to August 2006 and October 2011 articles were:

• Stedman native Bruce Langston was a Navy doctor who treated fellow prisoners during his 41 months in captivity.

He returned to the local area after being liberated and settled in Fayetteville, where he practiced urology until his death in 1970.

• Fayetteville native Col. Edmund P. Lilly was a POW who had commanded a battalion of Philippine Scouts. He spent another six years in the Army after returning home and retired in Fayetteville in 1954.

• Col. Richard Mallonee, an artillery captain at then-Fort Bragg in the 1930s, became a prisoner of war when he was commander of an artillery unit in the Philippines. After the war, he was a deputy post commander for then-Fort Bragg. He directed the first postwar housing development known as Mallonee Village.

• Fayetteville native Col. Phillip Fry commanded the 3rd Battalion, 57th Infantry Regiment known as the Philippine Scouts, which was a unit of Filipino enlisted men and American officers.

• An April 2015 obituary for Alcide “Bull” Sylvio Benini states that he arrived in the Philippines in June 1940 and was captured April 7, 1942.

He survived the Bataan Death March, Japanese “death ships,” and POW camps, according to his obituary.

After the war, he served with the 82nd Airborne Division Pathfinder platoon.

According to a 2009 interview with Benini for the Special Warfare School Heritage Center, Benini was one of the first instructors for the then-newly created Special Forces in 1952.

The following year he left the Army to enlist in the Air Force to establish the Air Force Pathfinders, which was renamed combat controllers, the obituary stated.

He retired from the Air Force as a chief master sergeant. The Benini Heritage Center and Museum, located at the Combat Control School at Pope Army Airfield, is named after him.

• Retired Lt. Gen. Thomas J.H. Trapnell was a Bataan Death March survivor, according to a February 2002 obituary in a Midland County, Michigan newspaper.

Trapnell, who retired from the Army in 1962 at the rank of lieutenant general, was serving as a squadron commander with the 26th Cavalry regiment in the Philippines when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941.

Trapnell was part of the 13-day, 60-mile march in which 650 Americans and 10,000 Filipino soldiers died.

Trapnell was imprisoned in Camp O'Donnell in the Philippines and then Cabanatuan, where thousands of Americans died by the end of 1942.

Staff writer Rachael Riley can be reached at rriley@fayobserver.com or 910-486-3528.

This article originally appeared on The Fayetteville Observer: Fayetteville and Fort Liberty links to Bataan Death March, POW camps