At Steve Hogue Enterprises, One-Off Cars Get a Second Shot at Life

What is the actual work in bodywork? You might picture panel beaters amid a whirlwind of pounding and thrashing metal. In shops that deal with modern cars, there's liable to be more cutting, welding, and painting, as it's often easier and cheaper to replace, rather than repair, damaged exterior components.

But the hardest jobs-cars for which parts are hard to find or nonexistent-require something else entirely: imagination. That's the sort of bodywork Steve Hogue enjoys.

"Give us the one-off car where there's no information-that's what we like to do," he says.

Steve Hogue Enterprises, now a three-man operation, opened 25 years ago as a more-or-less typical SoCal body shop. "First I was making muscle cars," he says. "Then I did a lot of hot rods where a guy gave me a drawing and I built it." As he gained experience, Hogue turned to large, coachbuilt vehicles from Lincoln, Packard, and Stutz. Later on, his shop began working on cars that were once considered beyond repair-good enough only for spare parts. Then Hogue started restoring cars that were so far gone, some people wouldn't even take them for parts.

These days, Hogue primarily sees vintage sports cars, which he has always liked best. "They're just the right size, and they're more fun to research."

The rare breeds rolling into his Torrance, California, shop-Shelby Cobras, early Porsches-are often worn to flimsy skeletons by time, trouble, and neglect. "It's kind of like working with dinosaur fossils," Hogue says. "Not everything is there, so I have to figure it out and make it complete."

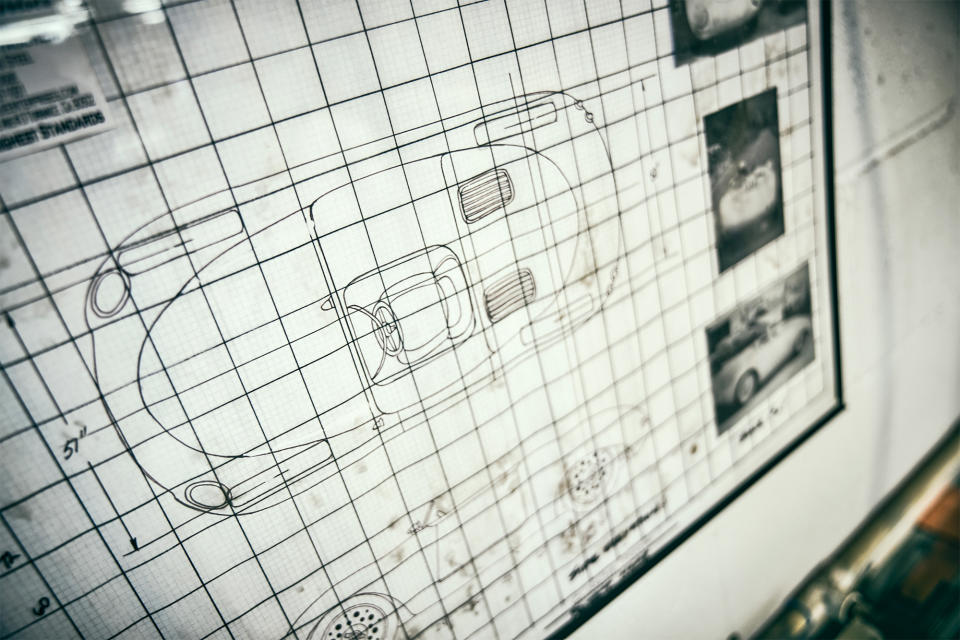

Sometimes, Hogue starts from little more than a photograph and a conversation with the owner to decide exactly which version of the car to restore. "It may have morphed several times over its lifetime, especially if it's been raced," he notes. Just determining what such a car is supposed to look like is a challenge. "A lot of shops now are focused on scanning and digitizing shapes, and when they don't have another car to copy, they can get lost."

Hogue's latest, typically atypical project is a 1961 Porsche 718 RS 61 Spyder-one of 13 built-with hastily hammered, ill-fitting aluminum in place of its original nose.

Once the working drawings come together, Hogue builds a body buck, a tool used for fitting as well as shaping and defining the metal. Making the buck can take hundreds of hours, sometimes as long as building the body itself.

Only then does the racket of panel beating commence. First, Hogue works on the broad form, pounding 0.050-inch metal panels against sandbags. After using an English wheel to shape the panels to the body buck, Hogue feeds the metal through a series of pneumatically powered, fast-acting hammers set up in stations. The machines pound away in ear-splitting, staccato bursts-imagine an army of angry elves with gavels-as he twists the piece this way and that. Short-stroke planishing hammers pound out details, smooth the shape, and finish the metal. "If I could only have one tool in here, it would be a planishing hammer," he says. "It can do everything."

Hogue isn't a slave to tradition. He constructs his bucks out of metal rather than old-fashioned wood, which he decries as dusty and messy. He just laughs when asked whether he uses lead for body filler, as on the "lead sleds" of the Forties and Fifties. "It takes two years for a lead patch to off-gas. The modern paint we have to use these days cures quickly, so you'll see the shadow of the lead patch underneath as it continues to cure." But, he adds, filler of any kind is an imperfect solution. "The idea in this shop is to make the metal good enough so you don't need filler."

When it comes time to hang the metal on the buck, years of experience have taught Hogue to start in the center of the car, where the A-pillar meets the body. He uses Vise-Grip C-clamps to fix the panels in place. Hogue hunches over a seam between panels while he welds. The quality, cleanliness, and symmetry of his welding bead says it all: The guy's a master.

This considered approach can often yield better-than-new results, although that's partly an indicator of the indifference with which some sports cars were originally built, Hogue notes, specifically calling out the Porsche 356. "When you look at the size of the jigs they were using, it's because the pieces had to be forced into position, like they were bending the car into shape," he says. "It's understandable, because I figure they were really pushing the cars out the door so they could make enough money to keep the business alive."

Hogue's process is by no means easy or inexpensive. Totally rebodied cars represent about 1000 hours of labor. Intensive projects take even more. "A Porsche 356 Pre-A that needs a chassis rebuild as well as a body would be about 1500 hours," he says. A regular, mass-produced car can be beaten, Bondoed, or welded into shape more economically elsewhere. Which is fine by Hogue. He's interested in rediscovering and honoring the work of earlier skilled craftsmen.

"Any car that's made by hand is unique-different from the car that came before it in the production series and the car that came after it."

There are certainly moments of intense and noisy work at Hogue's shop. But more often this is a place of quiet concentration. Hogue is really a coachbuilder, not a panel beater. With a combination of stunning craftsmanship and breathtaking artistry, he can make a car materialize out of thin air and take the shape it was born to wear.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos