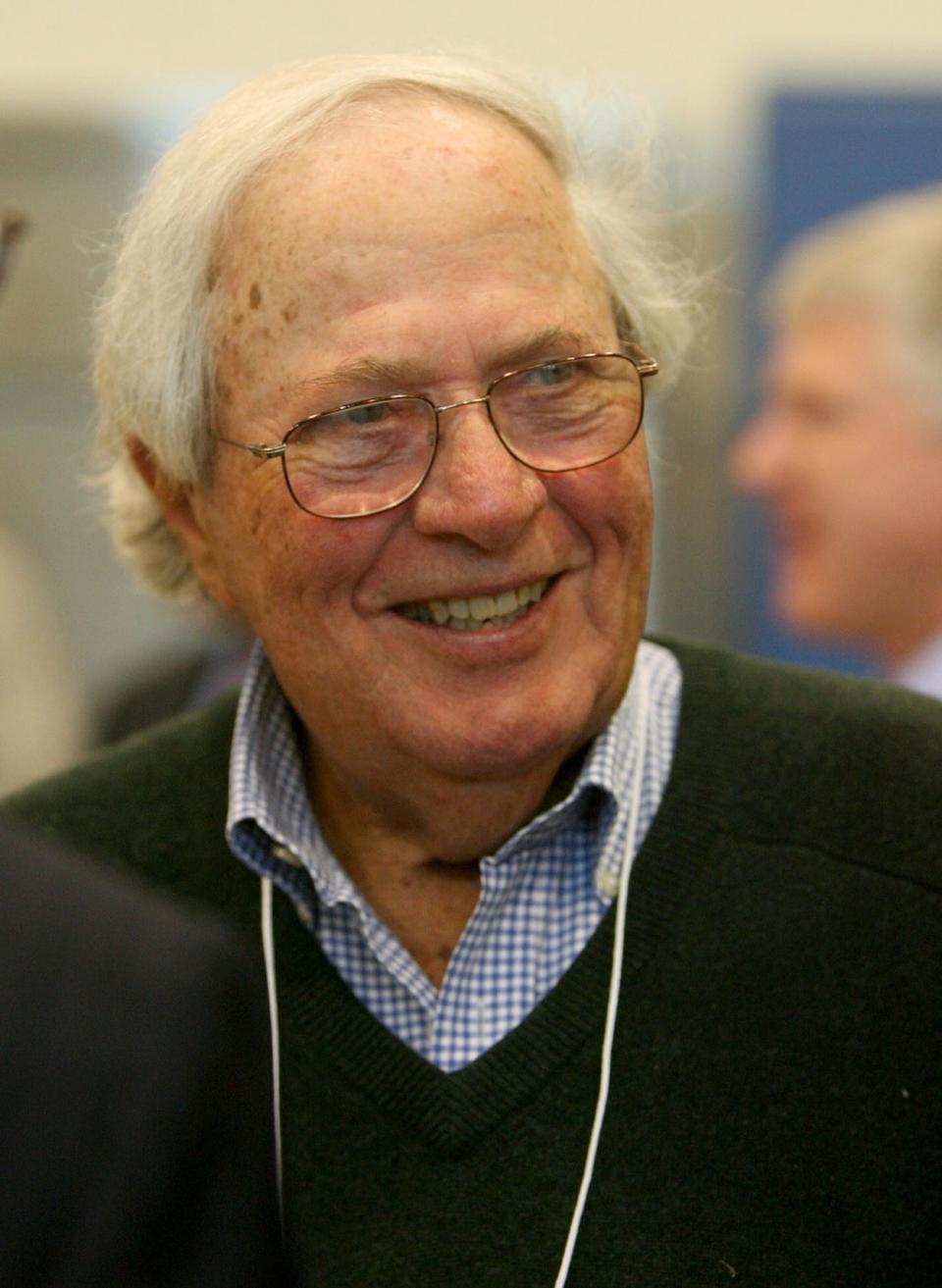

Stanley Goldstein helped create CVS. Here's why his family says he won't be forgotten.

Stanley Goldstein, a kid from Woonsocket who grew up humbly and founded a tiny company called Consumer Value Stores that grew into the gigantic CVS Health corporation, sadly left us Tuesday afternoon at his Providence home at age 89 after being diagnosed with cancer a month ago.

It is no overstatement to say that Stanley reordered a part of American retailing. When he and his brother Sid created CVS in 1963, drugstores basically didn’t exist. Most health and beauty items were sold in grocery aisles.

Stanley helped change that.

But speaking about him Tuesday, his wife, Merle, and sons Larry and Gene told me that never changed Stanley’s down-to-earth nature. He remained an informal guy from Woonsocket who loved his golden retrievers, clamming with his feet and the frayed collared shirts he wouldn’t give up because they were comfortable. He was a fan of the Patriots, Bruins, Celtics and Red Sox, and hated the Yankees.

“So he wasn’t fancy?” I asked.

His son Larry, a developer who lives in Providence, laughed. “That’s a capital N and a capital O,” he said.

Stanley remained proud that CVS headquarters is still in the working-class city of his roots, even though it now has almost 9,300 stores nationwide, and with $322 billion in revenue, is the sixth-biggest firm in the United States, larger than Google’s Alphabet, Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway and Microsoft.

But Stanley, said his wife, Merle, felt his other legacies were equally important, including philanthropy. Their Goldstein family foundation, called ELMS after the parents’ and sons' first names, gave away millions over the years, especially to education, a priority Stanley “lived” by spending years as board chair of Providence’s Met School.

For more than four decades, Stanley and Merle spent summers at a home on Caleb’s Pond on Chappaquiddick Island. Most mornings, Stanley would get in his 17-foot Boston Whaler and motor a few minutes across the harbor to Edgartown, where he would buy newspapers at a corner store, then have breakfast at the casual Dock Street Diner, ordering two eggs over hard, a single slice of toast, some bacon and home fries well done with onions.

Stanley would sometimes kid the staff by asking for portabello mushrooms and Feta cheese, knowing that with a small kitchen, no tables and 10 counter stools, they didn’t carry things like that. The waitress there called him, “Stan the Man,” and probably didn’t know he was CEO of a Fortune 10 company because he was never the kind to flaunt it, especially to the local fisherman he enjoyed chatting with.

I once saw Stanley Goldstein’s informality at a fundraising party at his East Side home. A server came by with grilled shrimp hors d’oeuvres on a tray. Stanley ate one, wasn’t sure what to do with the tail, looked furtively back and forth, then tossed it into a nearby decorative vase. I later tattled on him to his wife, who laughed and said yes, that sounded like her husband.

Stanley Goldstein and his three brothers grew up on the first floor of a Woonsocket triple-decker on working class Burnside Avenue.

Their dad, Israel Goldstein, sold bags and other paper goods to grocery stores, which in time began buying such items directly, undercutting the family's business.

The Goldsteins had also been stocking things like toothpaste, shampoo, shaving cream and Band-Aids by the cash registers. To make up for the lost bag revenue, Stanley’s older brothers started a company called Mark Steven, named after the family’s first grandchild, to expand their health and beauty items to the grocery aisle area.

Stanley joined the company after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania in 1955 and serving two years in the Army.

By then, Stanley’s college roommate Harold Cohen, who would become his lifelong friend, introduced him to Merle Katz. Harold and Merle, who at that point was finishing Boston University, had grown up together in Buffalo.

Merle found Stanley down to earth and a straight-shooter and they married four months later, first moving to Hartford and then New Haven, where Stanley worked “rack jobbing” with the family company, marketing health and beauty goods to grocery aisles.

He didn’t love it, and decided to switch careers, becoming a stockbroker in Providence.

But a few years later, in 1962, his older brother died in a small plane crash on a business trip. Not long after, his other brother, Sid, called Stanley.

![A company photo of the first of the Consumer Value Stores – later shortened to CVS – located in Lowell, Mass. [Provided by CVS]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/FSIG.INw.hadnVcmJlbxiQ--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTczNA--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/the-providence-journal/9c2e64d3e800ab586a18cf42e5a957ea)

Sid cut right to it.

“Larry’s gone,” he said. And their dad had recently died, too. “I’d really like you to come back.”

It was good timing because Stanley’s stockbroker job had been struggling due to a down market.

He joined up, and now it was Stanley, Sid and a Princeton grad they’d brought aboard named Ralph Hoagland who’d worked at Procter & Gamble.

The three were a good team.

“Ralph was the wild man who’d push the envelope,” Stanley once recalled when I interviewed him in 2017. “Sid was quite conservative. And I was in the middle.”

But soon grocery stores did it again – now they began competing in health and beauty products themselves.

So the three began to consider a complete change.

“We looked at nursing homes,” said Stanley, “roller-skating parks – all sorts of crazy stuff.”

If any of those had worked out, history might have changed and there would be no CVS.

Instead, at a convention, the three heard about a novel approach – a few dedicated stores in Pennsylvania called “White Cross” were selling only health and beauty products. That was a first, such items having been sold in groceries until then.

They sent Ralph down to stand outside one of the stores writing down sales from the visible cash register numbers, and back in Woonsocket, the three agreed the business model had potential.

So they took a leap, opening what they called a “Consumer Value Store” with discount items in Lowell, Massachusetts, feeling bargain prices might work there.

But to make the store stand out, they decided to have a much bigger selection of items than the White Cross stores had.

And one other strategy.

“We made each department better than its competitors,” said Stanley. “If you’re going to carry candy, make sure everyone says, ‘Wow, that’s where you want to buy your candy.’”

It became the first fully developed free-standing drugstore.

When I interviewed him, I asked Stanley why they shortened the name to CVS.

It got a chuckle. The signs, he said, were less expensive.

“All those letters cost a lot of money.”

They were nervous, but within weeks, the store showed promise, and today, the late Stanley Goldstein’s company is one of the nation’s biggest.

I asked Stanley why he felt CVS succeeded where other drugstore chains failed or lagged.

“It’s as simple as listening to your customers,” he said. “Don’t think, ‘Let’s make a profit this way or that way.’ You satisfy your customers, you’ll do fine.”

Speaking about it Tuesday in their home, Merle also said Stanley had just the right amount of boldness. He wasn’t the kind to take dangerous risks, she said, but he was willing to leap at new opportunities others might have shied from.

“He wasn’t afraid,” she said.

One example: In 1969, to help CVS grow, the company merged with Melville Corporation, which owned many unrelated retail chains including Marshall’s, which later was bought by T.J. Maxx. Stanley was named CEO, going from managing a $20-million-a-year drugstore chain to a conglomerate with billions in sales.

But his love was for CVS, and in 1996 Melville spun it off, and Stanley was delighted to return to just running his ancestral business.

Things seem to have worked out for him.

But as Merle and Larry talked about Stanley, they said he would want his other life achievements and passions equally emphasized – if not more so.

That would include the five golden retrievers he owned through his adulthood – two named Jenny, two named Mary and one Annie.

Larry joked about his dad’s priorities: “It was always the dog, then Merle, then Gene and I would rank third and fourth.”

More seriously, Merle said their marriage worked well because they enjoyed what they shared and encouraged each other to do the things they liked separately.

“I liked to go hiking, he hated it,” Merle said. “We used to go skiing – he hated that.” Stanley went on one family trip to Waterville Valley, but his beloved cigar froze, so he never went back.

“And I didn’t care that he went off on his golf trips,” Merle said. “That’s why we lived so well together all these years, he let me be me and I let him be him.”

More on CVS: CVS is headquartered in RI, but how big is their footprint here? What we found.

Larry said his dad also loved sailing his 100-year-old wooden Herreshoff 12½-foot sailboat in Edgartown Harbor.

“He liked to go nowhere,” said Larry, “just go out in the harbor, smoke a cigar and listen to the Red Sox.”

But although the Chappy summer home became a place Stanley Goldstein loved, Larry said his dad always had a fond spot in his heart for Woonsocket, which is why he was glad the CVS world headquarters has remained there.

Stanley would sometimes even go back to his old street, said Larry, and he liked that it had barely changed since the 1950s.

Because those were Stanley Goldstein’s roots.

And the beginning of an extraordinary Rhode Island life.

mpatinki@providencejournal

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: CVS founder Stanley Goldstein remembered for not being afraid of risk