How are RI's fish ladders working? Scientists await word from the river herring.

SOUTH KINGSTOWN – A seagull, standing on a rock in the Saugatucket River, waddled closer to the seam of foamy water swirling by.

There, in the crashing shallows below the Main Street Dam, the gull lowered its yellow beak. It cocked its head sideways as if to get a better view into the current.

“It definitely knows,” said Ed Albanese, 72, of Wakefield, who, like the gull, had come to watch the water at the entrance to the herring fish ladder. “It’s waiting. That’s amazing.”

Around the expectant gull, and around the curious Ed Albanese, a blustery March morning bloomed as bright as a daffodil while motorists and other pedestrians passed over the river, seemingly oblivious to the approaching homecoming.

But about a mile upstream at a second fish ladder, and then several miles farther up still at a third fish passage where the river’s natal headwaters spill out of Indian Lake, state fisheries biologist Patrick McGee and a half-dozen partners were preparing for spring’s annual return of tens of thousands of spawning river herring.

Critically important herring were decimated by Industrial Revolution dams

The question all along the Saugatucket this season is this: What will the fish, back from the sea, say they need?

Electricity will carry their message.

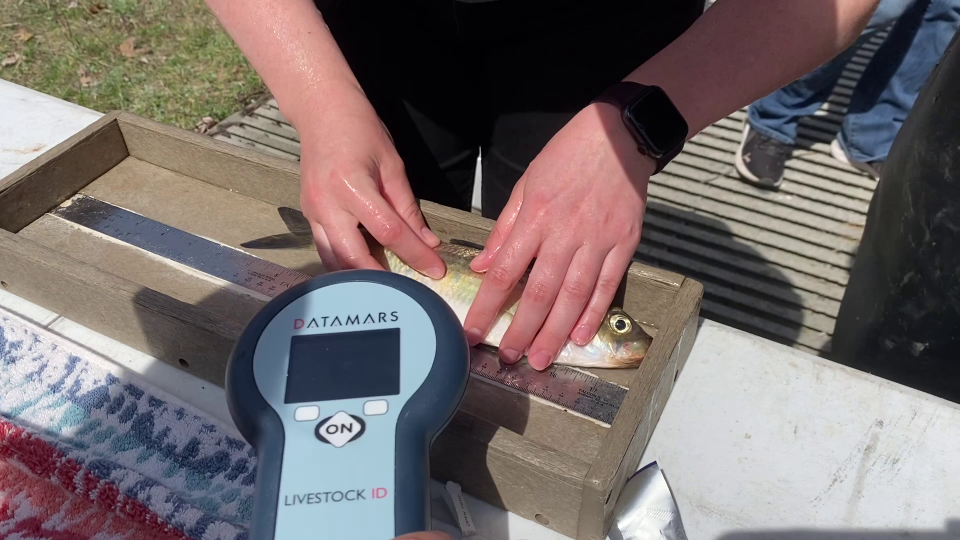

Over the last two years, scientists with the state Department of Environmental Management, The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have teamed up to implant tiny electronic trackers in the abdomens of about 700 returning herring.

Now they hope that antennae they’re placing at the entrances and exits of the Saugatucket’s three fish ladders will detect those tagged fish as they come by, helping the scientists better understand how recent design improvements in the ladders are working.

That knowledge, said McGee, might help improve fish ladders in other states that are also trying to restore the spawning runs of one of the most important forage fish along the Atlantic Ocean, once decimated by the dams of the Industrial Revolution.

“Between all our partners and the hundreds of volunteers who have helped us, we’re all kind of looking and waiting and seeing if all this time and all this effort and all this money that’s been spent is benefiting the [fish] populations,” said McGee.

How this year's herring will speak

As McGee and his DEM crew were setting up the first of four antennae at the Indian Lake fish passage, Sarah Paulson and Ophelia McGrail of The Nature Conservancy were positioning the box of computer electronics nearby that will collect and store the data coming from the fish tags.

The data can capture, among other information, which specific fish has returned, how many times it tried to scale each ladder, where it rested along the way and how much time it took to scale each ladder. A herring can move through the river in as little as two or three days, but often it takes one or two weeks.

"So, the four antennae at each ladder helps us access how the fish are behaving at each specific spot,” said Paulson.

Combined, the tracking system can also log how much time it took each tagged fish to navigate the miles of river between the Main Street fish ladder and Indian Lake.

Fish ladders were originally designed for salmon

Many older fish ladders were designed to suit salmon, which are strong swimmers and can jump. The 10-inch herring lack those abilities. Consequently, they often found earlier ladders too steep and their water flows too strong to conquer.

A decade ago, conservation groups redesigned and repositioned the Saugatucket’s Main Street fish ladder to make it easier for herring to find its entrance and scale it. Similarly, they installed wooden baffles at the second ladder at Palisades Mill to slow the flow.

Now scientists want to know how those improvements are working.

Herring live a perilous life

Of the more than 400 herring tagged during the spring run of 2022, the tracking system detected about 30 fish returning last spring. Their embedded tags pinged away as the fish traversed the 7.2 miles between Point Judith Pond on the coast and Indian Lake.

That is not a lot of tagged fish to get reliable data from, which makes this final year of information collection important.

Last spring the scientists tagged another 300 or so fish. How many of those fish and those tagged in 2022 will be detected in the coming weeks as the run starts is impossible to predict.

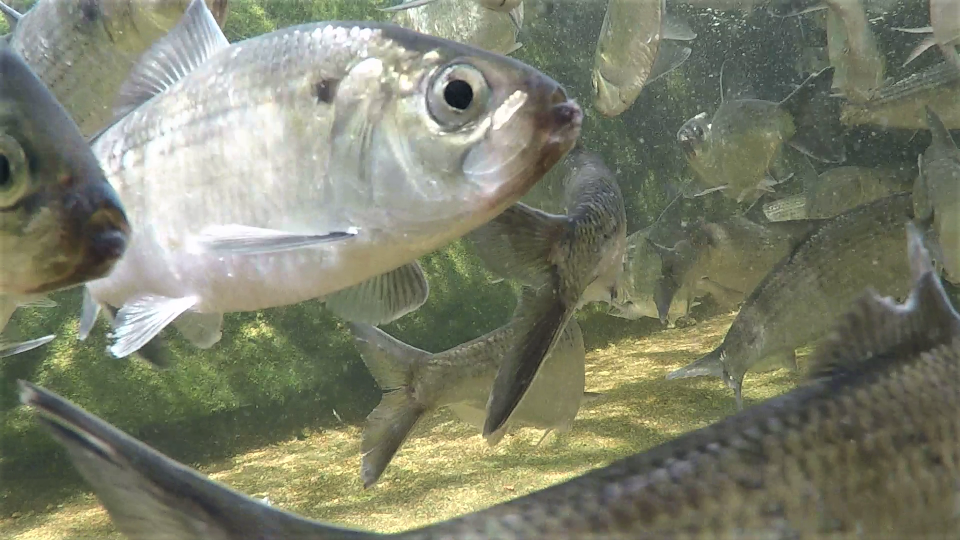

A herring lives a perilous life, after all. Everything wants to eat it.

“Last year we even had a cormorant in the fish ladder at the Main Street ladder at one point,” said Paulson.

“The adults come up and the juveniles go down [in the summer], and both ways they get picked off,” she said.

More: Narragansett Bay is changing forever. Here's why one fish is never coming back.

Cormorants, ospreys, seagulls. They all feast on the seasonal buffet.

“They take an absolute beating coming in every year,” said McGee.

River herring, which are a mix of alewives and blueback herring, spend much of the year 150 to 200 miles offshore. There as well, they run into a gauntlet of predators, from seals and whales to striped bass and tuna.

There is also the potential of getting hauled up as bycatch with other similar species, like Atlantic herring.

In 2006, Rhode Island joined other states in banning the taking of river herring.

Given a chance, and with river dams and impediments being removed, the fish are finding their way through several Rhode Island river systems.

They are determined.

A herring, confronted by low water, will turn on its side, said McGee, and flap through a trickling section of stream rather than surrender and quit its journey.

Back down at the Main Street dam, the once lone seagull is joined by another. An osprey soars above.

The stage is set for April's big push.

Predators, McGee said, often leave the first clue of the herring’s arrival even before the first finned harbinger of the season is actually seen: fish scales drifting along with the current.

That's how scientist know the fish are in.

"We kind of see them coming,” said McGee, “before we see them coming.”

Contact Tom Mooney at: tmooney@providencejournal.com.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: RI's river herring run is coming. How the fish can speak to scientists