Rare 4.8 earthquake offers ‘teachable moments’ for preparing for worse disasters

Within minutes of a Friday morning earthquake that struck the Northeast, New York City’s emergency management officials set out to check for damage, said Jackie Bray, commissioner of the New York State Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services.

Under the state’s emergency operations plan, city and state structural engineers were immediately deployed to inspect bridges, tunnels and other key infrastructure, and nuclear plants were required to report any damage within 15 minutes, she said. They found nothing significant, Bray said.

But experts say it’s still worth considering what could have gone wrong. “These are important teachable moments for what-ifs, and what would we do if it was worse,” said Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University.

Earthquakes are “not prioritized as highly as other scenarios on the East Coast and as you might see in more seismically active areas like the West Coast and countries like Japan,” added Schlegelmilch, who has authored two books about disaster preparedness. “There are plans in place and planning efforts, but obviously the ones that we get hit with more frequently, like coastal storms and extreme weather events, typically are more front of mind.”

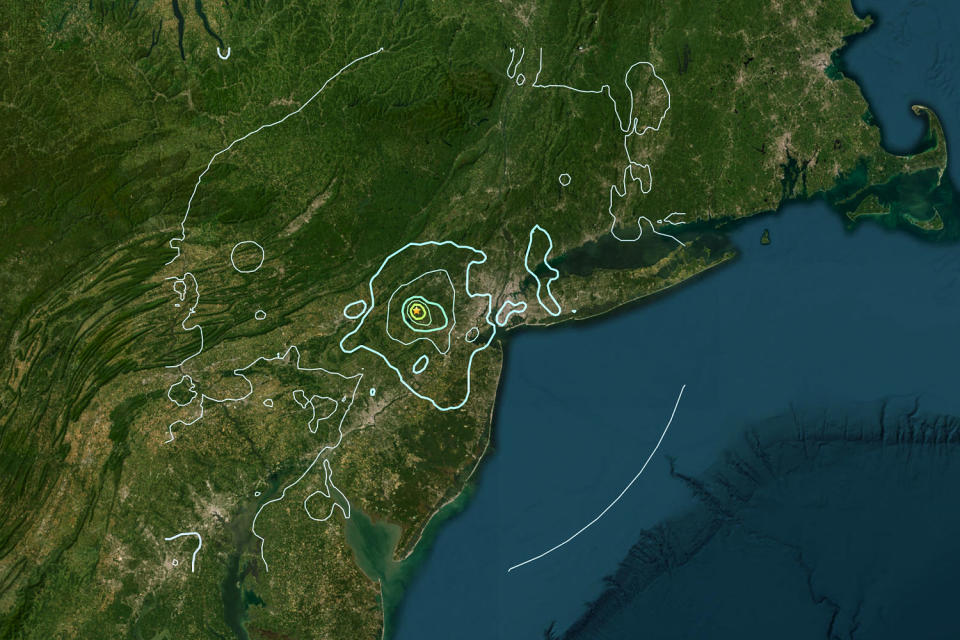

Friday’s earthquake, with an epicenter near Lebanon, N.J., took the region off guard. “It’s not like a blizzard in Buffalo, right, that you know you’re going to have each year,” Bray said. “An earthquake is unexpected in New York.”

Still, the state and city have put earthquake-specific measures in place, including adopting building codes that require new buildings or those being significantly renovated “to be built to the appropriate seismic standards,” Bray said, “so it is something that we are prepared for when it does happen.”

While New York City and other large urban areas in the Northeast have generally adopted the latest seismic building standards recommended by the American Society of Civil Engineers, such codes aren’t universal. Myriad state and local jurisdictions oversee building regulations and choose which standards to adopt for their communities, noted Emily Guglielmo, who chairs the engineering society’s seismic committee overseeing standards for new buildings.

“There are lots of different models,” Guglielmo said. “But it’s fair to say a larger city is more sophisticated and able to accommodate code changes more than a smaller jurisdiction.”

Such standards are not pegged to the magnitude of earthquake, but rather to “probabilities of collapse” — an assessment that differs based on regional earthquake-risk criteria and attempts to design equal safety standards nationwide, Guglielmo said.

“Obviously, the ground motions, the seismic risk, is higher in California than New York, and so we’re going to design for a higher force in California than we would in New York,” she said.

Though generally less frequent and smaller than those on the West Coast, earthquakes tend to be felt far more widely on the East Coast, said Paul Segall, a professor of geophysics at Stanford University. That’s because colder, older rock beneath the Earth’s surface on the East Coast is less absorbent than the warmer rock out West, he said.

Segall noted the 5.8-magnitude Mineral Springs earthquake that struck Virginia in 2011 “was probably felt by more people than any other in the history of the United States.”

Though today’s earthquake didn’t cause major harm, Segall said he wouldn’t rule out a bigger East Coast quake in the future. “The overall hazard there is considerably lower than in California and the Pacific Northwest, but it’s not zero.”

New York City and other East Coast cities generally have an abundance of older masonry and stone buildings that “perform poorly in seismic shaking,” Segall added.

Unlike some jurisdictions in earthquake-prone California that require older homes and buildings to be retrofitted to modern seismic standards, New York’s building codes generally don't do that. Most of the city’s housing stock was built before 1995, when the codes were adopted.

“It’s all about weighing risks,” Bray said. “These are rare events and, you know, today we saw 45 miles west of Manhattan a 4.8-magnitude earthquake with really either no or minimal impacts to infrastructure. That’s good news for all of us. I think at this point we’re appropriately weighing the risk factors.”

The lack of damage reported Friday should generally give the public confidence, Guglielmo said.

“I realize some ground shaking and building swaying can be unsettling to those who have not felt it frequently,” she said. “However, the performance of the infrastructure is showing they should feel very safe in their communities.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com