Opinion: What conservatives don’t get about the protests roiling college campuses

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

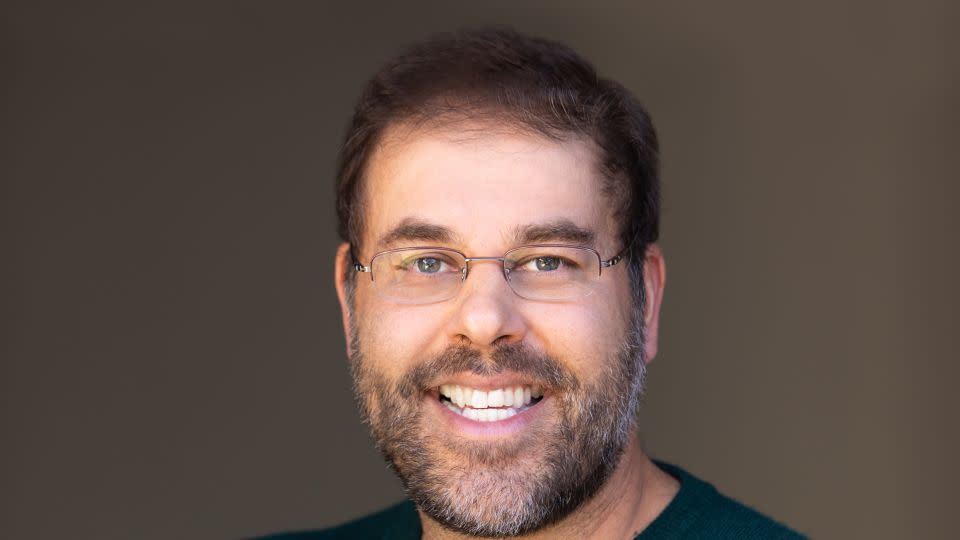

Editor’s Note: Jeremi Suri holds the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a professor in the History Department and the LBJ School. He is the author and editor of eleven books, most recently “Civil War By Other Means: America’s Long and Unfinished Fight for Democracy” and including “Power and Protest: Global Revolution and the Rise of Détente.” He is the co-host of the podcast, “This is Democracy.” The views expressed here are his own. Read more opinion on CNN.

In May 2001 President George W. Bush spoke at my graduation from Yale. He knew that few of the students and faculty in the audience had voted for him. But Bush still expressed “gratitude” for the liberal professors who modeled “dedication and high standards of learning.” “They’re the ones who keep Yale going,” the president — an alumnus from a family full of alumni — admitted. He proudly called himself a “Yale man.”

Many prominent figures in the Republican Party have the same elite university pedigree as Bush, but few show the respect for campus life that the president expressed in 2001. To the contrary, some Republican leaders have spent the last two decades condemning everything about the universities that boosted their careers — the expertise on subjects like climate change, the values around diversity and inclusion, and even the commitment to teach a full history of our country.

This Republican war on universities is the essential history behind the current conflicts on campuses. The student protests and police crackdowns are a result of the attacks on universities since Bush’s presidency. These attacks have over the years undermined university leadership and provoked students, staff and faculty. External pressure has brought excessive police presence on to campuses, as witnessed across the country last week.

My own campus, the University of Texas at Austin, is a case study in this crisis. In 2008, Gov. Rick Perry, who succeeded former Gov. George W. Bush, announced “Seven Breakthrough Solutions” for higher education in the state, each of which undercut the research mission and freedom of inquiry on college campuses. When the president of the University of Texas at Austin (and former Perry supporter) William Powers pushed back, the governor began a campaign to fire his academic critics.

Thanks to the support of donors and friends around the state, Powers remained president and protected the autonomy of the university, but at an enormous cost to the institution’s relations with elected Republican leaders. Distrust and outright hostility toward the university became commonplace in the state legislature, especially as far-right Republicans increased their influence. Many university professors, staff and students returned the distrust and hostility to the elected officials who seemed so out of touch with life on campus.

In 2015, Greg Abbott, a proud University of Texas graduate, replaced Perry as governor. Hopes for improved relations rose, briefly. Accused of being insufficiently conservative by far-right members of the Republican Party, Abbott soon looked to strengthen his anti-establishment credentials, and universities were easy scapegoats. He joined a chorus of critics who accused the University of Texas of excluding and demeaning conservative voices.

In the interest of viewpoint diversity, conservative donors and the Texas legislature pushed for the creation of more spaces on campus to promote conservative causes, including free markets, traditional constitutional principles and strong national security policies. University leaders responded positively, helping to build more dynamic and well-endowed centers for this work than on any other peer campus in the country.

These centers, which continue to thrive, include the Clements Center for National Security, the Salem Center for Policy, the Civitas Institute, and, most recently, the School of Civic Leadership. I will attest that these centers have enhanced my research and the education of hundreds of my students, whether liberal, conservative or somewhere in-between.

At the same time that the conservative centers grew on campus, however, the Texas legislature prohibited training and recruitment for racial, gender and ethnic diversity. With the passage of Senate Bill 17 in 2023, universities in Texas could no longer “engage in diversity, equity, and inclusion activities.”

On my campus this has meant the abrupt shuttering of offices that helped minority students, faculty and staff adjust to university life. Military veterans and first-generation students can still get targeted support, but not African-American students from Houston or Latinx students from the Rio Grande Valley or transgender students from Dallas. In early April, more than 40 staff members who had worked on diversity, mostly from minority backgrounds, were fired.

At the same time, new staff were hired by the conservative centers. They continue to provide comfortable and highly-valued spaces for their students. This dynamic has clearly whitened the University of Texas at Austin, as evidenced by immediate difficulties recruiting and retaining faculty and students of color.

This context is crucial for understanding recent protests on my campus, and others around the country. Many students, staff and faculty, especially those from minority backgrounds, feel that they have suffered setback after setback at the hands of hostile politicians and deferential administrators. They feel that they have less influence over their universities than at any time in recent decades, and they are largely correct.

Public and private university leaders have become more distant from their own campuses as they focus on fund-raising and testifying before hostile federal and state legislatures. They are intensely cautious about doing anything that might antagonize a powerful politician or donor.

The demonstrations on behalf of Palestinians have roots in concerns about campus governance. After all, no one really believes that universities can somehow end this war.

There are, of course, good reasons why university leaders should not give in to protesters on these and other points. Many of the demands are naïve and one-sided. Some of the protests have devolved into antisemitic and other hateful behaviors that should be punished under campus behavior codes, when the evidence is clear and the perpetrators have been given due process.

But attacking the protesters (trying to “cancel” them), as happened when my university leaders brought police on to campus last week, only escalates the conflict and encourages more violence. The protesters already feel under siege from right-wing politicians and university administrators; police action reinforces that feeling and provokes more protest. So too do developments like the disclosure from the Republican Speaker of the House that he is considering reducing or eliminating federal funding for college campuses as protest continue.

We were in a similar situation in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when students, staff and faculty across the United States felt ignored and attacked by politicians who supported the Vietnam War, and the university leaders who deferred to them. Police repression – most notoriously at Kent State and Jackson State Universities in May 1970 – brought the conflict home, with death and injury to students, and extensive damage to campuses. We cannot let the current self-serving campaign that some politicians have waged against universities lead to the same results. We took a dangerous step in that direction last week.

What we need are politicians who, despite their disagreements with liberal professors, are willing to stand up for the benefits received from their own university education. Elected leaders in Texas and other states must, like President Bush, respect the “dedication and high standards of learning” on campuses and seek to preserve those values by engaging students, staff, and faculty in dialogue about how to reform our universities for mutual benefit. Political leaders should encourage university administrators to get out of their offices to talk directly with those who teach, research and learn every day.

Not all protesters will greet dialogue with openness, but many will. I know this from my own experience. The time has come to end what has been a long political war on universities. It no longer benefits anyone, except those who truly want to destroy higher education and build their careers by repressing the free speech of young, talented citizens.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com