Oklahoma grapples with American phenomenon of family annihilation: What we can learn

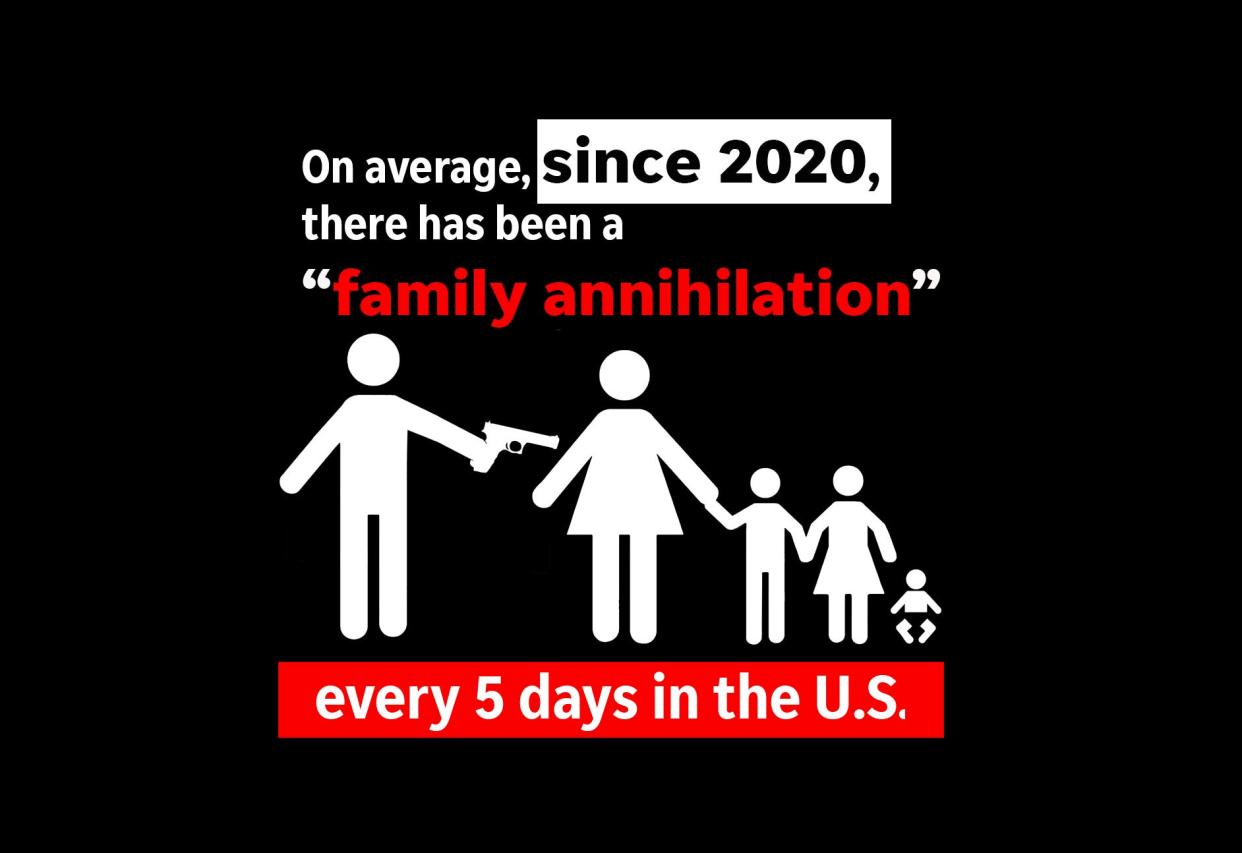

Police are describing the fatal shootings Monday of the Candy family in Yukon as a murder-suicide and a "massacre." But Jonathon Candy’s actions also carry a different name: "family annihilation," a violent phenomenon that each year takes hundreds of lives across the United States — and one that has shocked Oklahoma communities more than a dozen times since 2020.

“Family annihilation,” or familicide, occurs when an individual kills multiple family members — typically children, spouses or partners, and parents — in rapid succession. A majority of cases also end in suicide after the killer takes their own life.

According to data examined during a 2023 investigation by the Indianapolis Star — which, along with The Oklahoman, is part of the USA TODAY Network — there were at least six cases of “family annihilation” in Oklahoma between 2020 and 2023. Further research by The Oklahoman showed at least eight additional cases have been reported during and after the data analysis period.

In contrast, Texas has had at least 33 “family annihilation” incidents since 2020, while California has had at least eight, according to the database.

More: Candy family: What we know about the Yukon-area family whose 'souls radiated brightness'

From 2020 to 2022, the nation averaged 65 cases, with the highest being 73 in 2022, according to the Indianapolis Star. Texas, meanwhile, averaged 10 a year, while an examination from The Oklahoman showed Oklahoma is seeing an average of four a year.

Across the United States, the overall victim count from family annihilation averages 223 deaths a year.

The Oklahoma City Police Department, the lead investigative agency on the Candy familicide, said Tuesday the reason behind the murders "remains a mystery." As of Friday, police said the investigation had been closed.

What are the different types of family violence?

Julie Kafka, a postdoctoral scholar in the Firearm Injury & Policy Research Program at the University of Washington, is also an expert in intimate partner and family violence. She said people attempting to study family annihilation cases typically separate them into two psychological approaches: "murder by proxy" and "suicide by proxy."

For the "murder by proxy" theory, the killer sees the children as an extension of the victim and kills them as a final act of control. In the "suicide by proxy" theory, the annihilator kills their family because they feel they can no longer provide for them, deciding they want to take their own life but can't bear to leave the pain behind. This theory also draws from literature describing what sociologists call "anomic suicides."

"It's coming from this more suicidal place and that person just feeling possession and responsibility for the family — a kind of misguided altruism that they’re sparing the family’s suffering by ‘taking them with them,’” Kafka said.

Kafka further explained that "family annihilation" cases, compared with other crimes, are rare, but are difficult to study due to victims and perpetrators so often not living to tell about them. The criteria for what counts as a "family annihilation" also varies state by state and agency to agency, with some uncertain if a familicide should be defined by the deaths of a spouse and a family member or by two or three family members.

"But I think overall, what we can tell is, most often, these are tied to domestic violence histories," Kafka said. "These events don’t just come out of the blue, there’s usually some kind of violence history, warning patterns, psychological instability — but it’s not always clear to outsiders. It’s not necessarily like there’s something diagnosed. Unfortunately, the people who would see these warning signs most apparently are the ones who are no longer around."

What are the likely scenarios leading up to 'family annihilation'?

The Indianapolis Star examined 227 known "family annihilation" cases that occurred from Jan. 1, 2020, to April 30, 2023, and found several common threads in the tragedies that killed more than 750 people.

In a majority of cases, neither the police nor surviving family publicly disclosed a motive or other key stressors preceding the killings. As a result, contributing factors are likely underrepresented, but the cases still show a number of revelatory patterns.

Three scenarios frequently showed up in the "family annihilator" case data: Men who killed their wives, girlfriends and children; young men who killed their parents and siblings; and couples who killed their children together and then themselves.

Other findings included:

The killer was a male in 94% of the cases.

Primary risk factors include histories of domestic violence, substance abuse and access to guns.

A gun was used in about 86% of cases. Other methods include stabbing, strangulation, blunt force trauma, asphyxiation and arson.

More than three-quarters of the cases occurred in the South and the Midwest. Texas had the most — at least 33 — followed by Florida, Arizona and Ohio. Only 10 states and the District of Columbia had none.

More: What's behind the growing trend of a person, most often a man, killing their own family?

How many instances of 'family annihilation' have happened?

Recent cases in Oklahoma

Notable incidents of "family annihilation" have occurred in Oklahoma since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

More: Texas leads the nation in 'family annihilation' cases, study finds

Can cases of family annihilation be prevented?

The most extreme of those affected by domestic violence, "family annihilation" victims represent a fraction of the more than 15,000 men, women and children who die each year by the hand of a loved one or relative.

Domestic violence and abuse in Oklahoma is an epidemic of its own. Nearly half of all women in Oklahoma experience intimate partner violence at some point in their lives — the highest rate in the United States, according to data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey.

Oklahoma consistently has been ranked among the top 10 states for women killed by men in single-victim/single-offender incidents over the past three decades.

But because of the various problems in studying familicide across the country, Kafka said it is difficult to draw a direct correlation between Oklahoma’s high domestic violence rates and the number of family annihilation cases.

She has admitted, however, that it wouldn’t surprise her. For decades, the state has long lagged behind in mental health services, providers and professionals.

"It’s hard to draw a cause and effect, but I would also say it’s very likely that if we could increase funding and access to mental health services, domestic violence services, I would imagine we would have a better time of preventing these kinds of events," Kafka said. "And I think part of that also comes from trying to decrease the stigma around people saying they need help or getting their family members help that is needed."

But the stigma around both mental health care and domestic violence support programs is persistent and thorny, Kafka said, and it's often led to a misconception that the majority of people dealing with mental health struggles are violent threats to society. At the same time, however, experts agree that the best predictor of domestic violence is past behavior.

"I think that addressing domestic violence in a holistic way would tailor supports for children who might be exposed in the home, the victim survivor themselves, and the person who’s perpetrating harm," Kafka said. "We’re seeing now for the first time some really convincing evidence that there are ways we can help people stop being abusive, but there’s just not a lot of infrastructure yet to have those programs up and running. I think that’s a really big piece of the puzzle that we need to be thinking about as far as solutions, and I think mental health access and supports is also a piece of that."

Editor's note: If you or someone you know has suicidal thoughts, addictive tendencies, stress and other mental health issues, you can call or text 988, Oklahoma's Mental Health Hotline, or call 911.

Former Indianapolis Star reporter Mary Claire Molloy contributed to this story.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Family annihilation: Oklahoma grapples with American phenomenon