Officials are warning of a deadly drug cocktail. These users have already experienced it

Louis sat shirtless on the floor of a green-and-white camping tent, a used syringe on the floor near his feet.

Inches away lay the remnants of a wax stamp bag, typically used to package heroin or fentanyl. A silver spoon rested perpendicular to the syringe.

Outside the encampment dangled a red- and yellow-blossomed hanging plant, its Lowe’s tag still attached. About 10 feet away, a potted tomato stalk sat in the sun, waiting to be planted next to the 44-year-old’s small strawberry bush.

Louis has resided in wooded Dover encampments for about a month, though he has called this particular area home for the last two weeks. He came here after attempting to detox at a nearby facility.

In the short span from when Louis left detox to coming here, a new drug mixture made its way to Kent County. It’s so potent that public health officials and police have issued several warnings and recently held at least one news conference.

While officials have not said publicly where they believe the drug cocktail originated, those who work in addiction medicine believe it may have come up from Baltimore, first striking Sussex County and then Kent County.

They say it’s likely only a matter of days before it makes its way to New Castle County if it isn’t already there.

THE OVERDOSES: Police, state warn: 73 suspected drug overdoses, 2 deaths in 1 week in Sussex County

Between April 26 – when officials first noticed a surge in overdoses – and May 3, at least 83 people overdosed in Sussex, Delaware State Police said. More than 40 overdoses were recorded in Kent in that same time period.

At least five of those have been fatal.

Those who live in these Dover encampments don’t know much about the mixture’s origins, though they’re well aware of its effects. In the previous two or three days alone, not a single 24 hours had passed without someone in their group overdosing, said a woman named Kathryn who lives in a nearby camp.

Delaware Online/The News Journal is identifying these users only by their first names, given the stigma surrounding addiction and that they’re still actively struggling with the disease.

Health officials have said the overdoses caused by this mixture – a combination of xylazine, bromazolam, fentanyl, quinine and caffeine – are much more severe, with more than a dozen patients needing mechanical ventilation and intubation. Users have also required a significant amount of naloxone, better known by the brand name Narcan, to revive them.

With no apparent dissipation in sight, outreach workers are trying to flood Kent and Sussex encampments with naloxone in an attempt to mitigate the drug’s effects. But they’re also finding that some users, like Louis, are now taking their own steps to avoid the mixture.

“I haven’t overdosed, but I have seen a lot of people and it’s crazy,” the 44-year-old said from behind his half-open tent flap. “So I’m trying to stay away from the dope and looking for crack or (powder) cocaine.”

‘You almost died’

Louis has little, if any, access to the news, so it wasn’t until he was given the concoction that he knew there was something new in the local supply.

When he heated the drug, the mixture became clear, he said – the first sign it was different. Heroin and fentanyl often turn an opaque tan or brown, though these opioids can also develop into other colors when heated.

The texture was different, too, he said. When he smoked it, the taste was chemical-like – “like a pill, almost.”

It also hit him fast, Louis said.

The walk from his encampment to the Lowe’s in Dover usually takes him about 15 minutes. Somewhere along that walk, he passed out.

When he awoke, he was on a sidewalk between the home improvement store and Sam’s Club and had no idea how long he’d been down for. Initially, he also wasn’t sure where he was or what had happened.

He felt sluggish and disoriented, almost in a hangover-like state. He estimated that it took at least 45 minutes to get his bearings.

Within an hour or two, however, the drug’s effects had completely worn off, he said.

“There’s definitely something different about that” drug, Louis said, calling it by the word stamped on the blue wax packaging. (Delaware Online/The News Journal does not publish the names of packaged street drugs in an effort to not promote substances that are harming people.)

“I didn’t like it,” he added.

MORE: Overdose surge in Sussex: Beebe ER in Lewes sees over 30 overdoses in 6 days

At another nearby encampment, residents also appeared wary of the drug.

Kathryn, the woman who reported seeing numerous overdoses, said one man had repeatedly overdosed from the product. She’s been able to bring him back a few times by pouring water on his neck and sometimes the rest of his body, though that hasn't always worked.

“The second he doesn’t start coming back to me, I hit him with the Narcan,” said the petite 64-year-old, her body gaunt save for an arm infection that’s made her left forearm, hand and foot swell.

“He gets mad at me: ‘You ruined my buzz,’” she added. “I’m like, ‘Yeah, but you almost died.’”

Not long after Kathryn spoke these words, the young man she was with – her daughter’s boyfriend – produced an empty baggie of the substance, the ink from the stamp slightly smudged but its name still clearly visible.

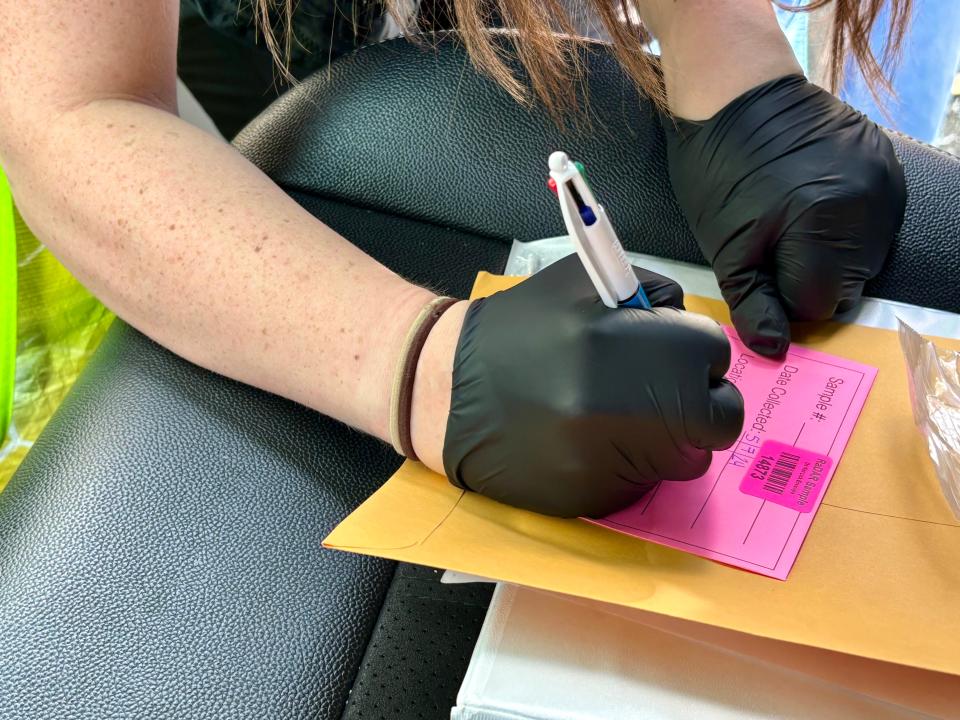

He handed it to a Brandywine Counseling and Community Services outreach worker, who placed it in a small plastic bag for testing. About 20 minutes later, in the passenger seat of her outreach van, she’d swabbed the packet with a cotton-tipped swabstick – the same type used for COVID-19 testing.

As she broke off the end of the stick and sealed the pink package, she explained that it would be sent out – likely to Maryland – for rapid testing. In a week to 10 days, they’d know exactly what they were dealing with.

Hopefully, they’d given out enough naloxone to last until then.

How to get help

Delaware Hope Line: 833-9-HOPEDE for free 24/7 counseling, coaching and support, as well as links to mental health, addiction and crisis services. Resources also can be found at helpisherede.com.

Suicide and Crisis Lifeline: 988

SAMHSA National Helpline: 800-662-HELP (4357) for free 24/7 substance abuse disorder treatment referral services. Treatment service locators also are available online at findtreatment.samhsa.gov or via text message by sending your ZIP code to 435748.

Got a story tip or idea? Send to Isabel Hughes at ihughes@delawareonline.com. For all things breaking news, follow her on X at @izzihughes_

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Delaware overdose surge leaves users wary, in need of Narcan