New North Port zoning could fix its tax base, but opponents fear overgrowth

North Port’s origins — products of both bad actors and bad luck — have left it to atone for the sins of its creators for the past 65 years.

The dilemma dates back to around 1958, when the General Development Corp. cut what would become Port Charlotte, Port St. Lucie, North Port and other unclaimed areas into “pre-platted” single-family plots. The company sold those lots and told clients it would build homes on them, but it failed to deliver the infrastructure to support them.

These lots have dominated North Port since it became an incorporated city in 1959, and the area continues to see an abundance of single-family home construction. For example, it issued 1,903 residential building permits compared to 61 commercial permits in the 2022-2023 fiscal year, according to its annual building activity report.

The layout has led to a skewed tax base, thanks to little room on the zoning map for commercial development and the steady stream of single-family home construction. Alaina Ray, North Port’s director of development services, said that distribution can’t last much longer.

“You can’t survive with the vast majority of your land being residential,” Ray said. “It’s going to be a significant impact on our homeowners if we don’t get this under control.”

More in North Port: Appeals court to hear oral arguments in residents' effort to separate from North Port

A healthy city, experts say, is comprised of around 20% non-residential, tax-generating property — 30% in a perfect world, but at least 18% to sustain itself without burdening its homeowners with the upkeep of public facilities. North Port has 8%.

Its undersized commercial base means funding falls on the backs of residents via property taxes and other fees. For now, the $8.4 million North Port received in American Rescue Plan Act funding and a bump in taxes thanks to higher property values last year are keeping the cashflow steady.

But that tap will sputter out eventually. When it does, North Port will either have to raise its millage rate — a fee assessed to each $1,000 of a home’s taxable value — or find another source of funding.

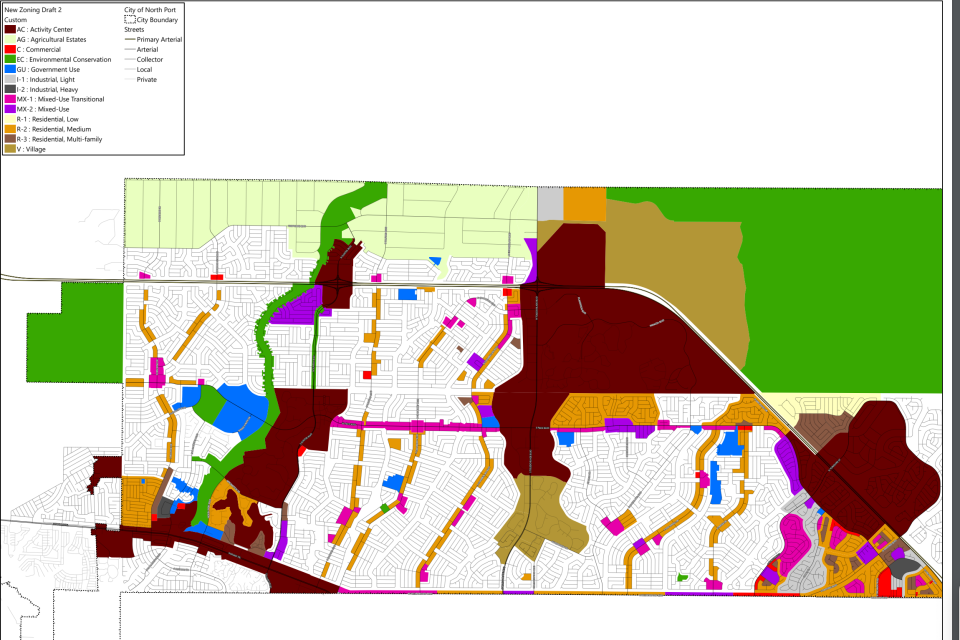

The ticking clock — punctuated by impending city projects like widening major roads and reworking the public water system — incited city staff to propose amending North Port’s Unified Land Development Code with a new zoning map. Introduced at a Nov. 6 City Commission Workshop, the map scatters mixed-use districts around some of North Port’s major residential areas in hopes of attracting new enterprises and easing the onslaught of single-family home construction.

The zoning draft adds new mixed-use districts along major corridors like Price Boulevard as well as established residential areas like South Yorkshire Street. These districts are meant for vertical integration — a type of development that includes residential and commercial space in the same building — and will replace some areas previously zoned commercial and single-family residential.

After decades of lagging behind on commercial development, city staff are hopeful the amended map will allow North Port to catch up. But longtime residents fear overgrowth and an onslaught of enterprise in a city that can’t handle it.

Backlash against new zoning persists from rural residents

The proposal has been met with widespread backlash since its introduction, particularly from residents in multi-acre properties and agricultural areas. A coalition of them — organized via the “No Rezone North Port FL” Facebook group with more than 300 followers — has protested the new the code, which the commission hopes to approve later this year.

Pam Tokarz, a North Port resident since 2018, leads the group. She lives on three acres in North Port’s agricultural district, where she sells fresh eggs laid by the chickens she keeps on her property.

A vocal opponent of the potential rezone, Tokarz studied the code and found red flags. Most notable to her, the draft tacks on commercial districts to the ends of neighborhoods: a combination Tokarz said is incompatible for residents and future businesses alike.

“There will be people in the area that have horses, pigs, cows and sheep,” Tokarz said. “Anything that goes along with those areas, like a rooster crowing at 5 in the morning, they should expect it.”

Tokarz and other opponents feel the impending growth is too much, too soon. With the rezone, residents fear excess traffic, overcrowding and general disruption to the quaint collection of neighborhoods they call home.

The proposed new North Port, they say, is fundamentally at odds with the North Port they know — and why they moved in the first place.

That abundance of residential property, while a financial nightmare for the city, is a transplant’s paradise. North Port has situated itself as a natural, suburban community with urban ties: close enough to bigger cities like Sarasota and Fort Myers but far removed enough to escape to peace and quiet.

More: Sarasota to consider private development at Ken Thompson Park, as residents cite concerns

The pitch was enough to draw Julie Braun and her husband, Greg, from Minnesota to North Port’s west side in 2012. They live on Barcelona Street, where they enjoy nature in their backyard and relish the open space their lot affords them.

The Brauns have seen single-family residences more than double — from 14 to 32 — on Barcelona Street since they moved down. The new zoning changes little about the area, which includes an activity center surrounded by residential parcels.

This doesn’t help the single-family growth problem, Julie Braun said, and the zoning at large only serves to create dysfunction. With proposed commercial districts interspersed between residences and single-family construction continuing, the Brauns are wary of mismatched districts that don’t complement each other.

“House, house, business, house, business, business, house,” Julie Braun said. “Like broken teeth.”

Development staff predicts North Port will incur enough commercial funding to build the necessary infrastructure in a decade or two, but opponents like Commissioner Debbie McDowell don’t buy it. McDowell, who’s been vocal in her dissent of the rezone, said there’s no guarantee the new commercial districts will draw commercial activity that fast — if at all.

McDowell echoes what many in the No Rezone coalition have insisted: North Port needs to address its infrastructure issues before it can invite developers to town.

“Too much, too fast, too soon,” McDowell said. “Where’s the plan?”

Why is North Port proposing a rezone now?

The Brauns and others would prefer North Port pause single-family construction, but more often than not, the city’s hands are tied.

Florida’s ban on building moratoriums for certain counties (including Sarasota) means a widespread halt on development isn’t possible. If a parcel owner — like many out-of-staters who have purchased property on single-family lots — checks all the boxes on their application to build a home or business, North Port legally can’t deny them.

The restrictions are glaring in the face of current growth, which is some of the most intense in the state.

Thanks to a surge of new residents at the turn of the century and another around 2016, North Port’s population has skyrocketed: more than 500% growth in the last 30 years, according to data from the Florida Office of Economic and Demographic Research. It now hosts more than 86,500 residents — the most of any municipality in Sarasota County.

For longtime locals like Mayor Alice White, the population surge isn’t surprising.

“There was no question that the city was going to grow,” White said. “People would eventually discover North Port like I did and go, ‘Hey, this is paradise.’”

More: Bradenton private school leader appears to violate federal tax law in congressional run

The growth is outpacing North Port’s upkeep capabilities.

Projects like widening Price Boulevard — one of the city’s major corridors — and restructuring the entire public water system have already broken ground, and a new Interstate 75 interchange and other improvements are on the horizon. If North Port’s tax base remains as-is, local funding for these projects will soon run dry.

It’s why proponents of the rezone like White have deemed it so necessary. Supporters hope more commercial development will both curb the single-family home issue and provide project funding from taxes and impact fees.

New enterprises, development staff predicts, will afford North Port the funds to sort out its infrastructure in a decade or two if the new zoning passes. And precedent proves, Ray said, that developers will pounce when they sniff out a rezone.

“It’s a certainty that it will happen,” Ray said. “We’re really the only and last place left for development along 75 in southwest Florida that will accommodate these types of industries.”

What exactly those industries are is still up for debate.

Some, like White, predict that commercial districts within neighborhoods will encourage a crop of mom-and-pops run from garages and living rooms. Others, like Ray, feel North Port is long overdue for an entertainment district or a proper downtown: bars, performance venues and the like. Sarasota Memorial Hospital’s future North Port campus — set for just off Interstate 75 on Sumter Boulevard — could also incite a wave of medial offices.

The uncertainty is alarming to rezone opponents like Tokarz, who fear larger chain businesses will result in overgrowth. Considering North Port is already lagging behind, supporters like White believe development in the areas zoned for it won’t yield more growth than necessary.

“I don’t even understand what that word means,” White said. “If this is property that was bought and sold based on its ability to be developed, what constitutes overdevelopment?”

Four of North Port’s five city commissioners — all except McDowell — have voiced their support for the rezone in various meetings and workshops. It’s uncertain when it will make an official city commission agenda, but city staff will implement the new ULDC if and when the commission approves it.

For now, the only guarantee is that life in North Port won’t stay the same. The city needs commercial development to survive, Ray said, and that means the multi-acre lifestyle many rural residents fell in love with could become a relic of a bygone era.

“We’re an incorporated city, and cities grow,” Ray said. “It was almost an illusion of being in the country, and they got to enjoy it for a long time.”

Contact Herald-Tribune Growth and Development Reporter Heather Bushman at hbushman@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter @hmb_1013.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Opponents fear overgrowth in North Port rezone