New Kavanaugh allegations don’t change the fact that it’s all about politics

In the day since Christine Blasey Ford stepped out of anonymity with her allegations that Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her when they were both teenagers, two other names have also come back into the news: Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and his former subordinate Anita Hill, who accused him of sexual harassment in testimony at his confirmation hearing in 1991.

The similarities are many — both women reluctantly came forward late in the confirmation process, accusing a powerful man of sexual misconduct in lurid detail. Both men denied the charges. Both women (both, coincidentally, professors) were met with vehement pushback from Republican supporters of the nominees.

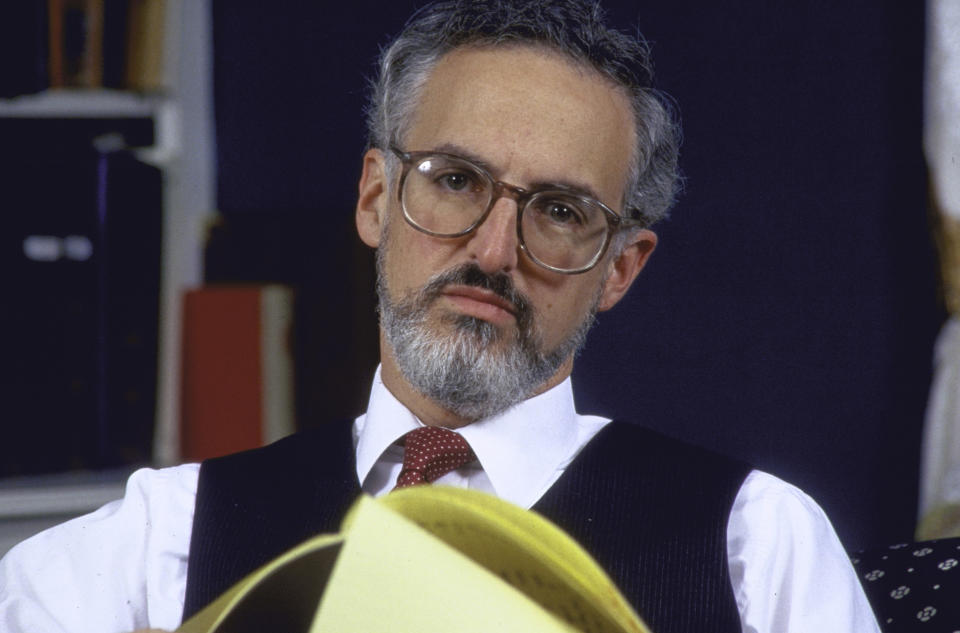

But there is another name, cited less often, whose nomination brought accusation and furor, and whose story is just as relevant, but in different ways — Douglas H. Ginsburg, nominated to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan in 1987. Like Kavanaugh, he was accused of breaking the law decades earlier: As a college student during the ’60s and ’70s, he had smoked marijuana.

Past is always a prologue, and, taken together, the outcomes of both the Ginsburg and Thomas nominations tell us a lot about where we stand now. The questions asked and not completely answered back then reflect how we have changed as a society, and how we have not.

The first question in all three cases is “did he do it?” Learning that National Public Radio’s Nina Totenberg was about to break the story, Ginsburg quickly admitted that he had smoked pot, then withdrew his name nine days after he was nominated.

Thomas vehemently insisted on his innocence, calling the hearings “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.” And Kavanaugh, similarly, has denied the accusations, issuing an early-morning statement: “This is a completely false allegation. I have never done anything like what the accuser describes — to her or to anyone.”

Is that the predictive takeaway? The guy who confesses doesn’t get to be a Supreme Court justice, whereas the ones who assert innocence are confirmed?

Things have changed since the Thomas hearings, starting with the very fact of those hearings. The way the Senate Judiciary Committee treated Hill — grilling her as though she were on trial, refusing to allow the testimony of a second woman with a similar story to tell — resulted in a voter backlash in the 1992 election that tripled the number of women in the Senate and sent a record number of women to the House.

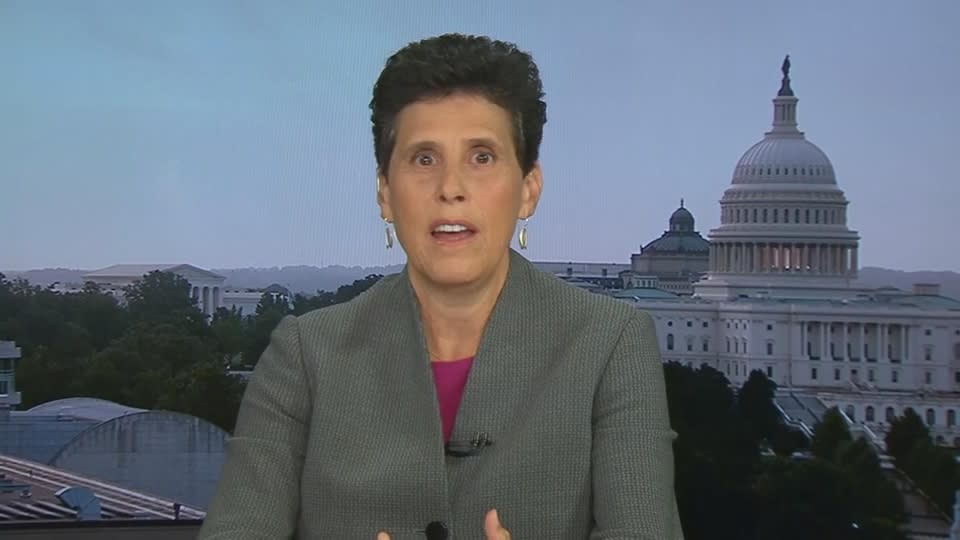

Critics said that the entirely male committee was not trying to find the truth, but rather trying to protect the nominee, a charge that Ford’s lawyer is echoing now. Debra Katz told ABC News that although Ford is “willing to cooperate,” she is not willing “to be part of this bloodletting that happens in Washington.

Republicans in Congress have been “saying that they’re going to fight this tooth and nail, that they’re going to grill her,” Katz said. “That’s hardly an effort to get into a fair and thorough investigation of what has occurred. If we’re really trying to get at the truth, the hearings should not be used to weaponize against those who accuse powerful men.”

Another difference since Hill stepped forward is the #MeToo movement, with its message that for too long, powerful men have been allowed to use that power against women, and that women should and would be believed. That altered landscape would suggest that these latest charges would have far more traction than Hill’s did in 1991.

Yes and no. Dozens of high-profile men have lost their jobs, campaigns and reputations after being accused of varying levels of sexual misconduct in the past year. One stark and telling exception, however, is the president of the United States, who has been accused of similar behavior by at least 13 women.

Perhaps, then, the common denominator for those who pay a price is proof: the existence of recordings, a parade of accusers, contemporaneous accounts and payments in exchange for silence. In most of the cases where high-level CEOs, entertainers and politicians have faced consequences, there has been at least one of the above. (Not so, again, in the case of the president, for whom all those elements of proof exist.)

Is there such proof in the Kavanaugh case? — clearly not the kind we have begun to demand in this technological age where we assume that all encounters must have left some electronic trail. But in her intended-to-be confidential letter to the FBI, Ford names a potential witness — another teenager she says was in the room when Kavanaugh allegedly pinned her down and attempted to remove her clothing.

That man has identified himself as Mark Judge, a classmate of Kavanaugh’s at Georgetown Preparatory School who told the Weekly Standard: “It’s just absolutely nuts. I never saw Brett act that way.” Mother Jones, in turn, has pointed to two separate memoirs written by Judge, both of which describe his high school days as filled with blackout drinking, suggesting, writer Stephanie Mencimer says, “that his memory of those days may not be entirely reliable.”

Will this count as “proof,” one way or another, particularly with #MeToo as a backdrop? To answer that question requires first tackling another: Even if proven, should it matter? What weight should be given to a misdeed, even a crime, from 36 years ago?

That’s where Ginsburg comes in. At the time, his defenders called his marijuana use “a youthful indiscretion,” stressing that it happened decades earlier. But against the message of the times — a president who gave speeches condemning the culture for its “flippant and irresponsible attitude toward drug use” and a first lady whose slogan was “Just Say No,” it was enough to derail Ginsburg. Even the idea that everybody does it didn’t help Ginsburg; two presidential candidates at the time, then-Sen. Al Gore, D-Tenn., and former Arizona Gov. Bruce Babbitt, made similar confessions, as did Newt Gingrich, then a Georgia Republican, and none of them paid a political price.

Ah, so the message of the Ginsburg derailment is that as a nation, we have decided that the child is the measure of the man, and some jobs, Supreme Court justice, for instance, require such unimpeachable proof of character that even decades-old missteps still matter? And as such, Ginsburg’s inability to advance to the court is the best answer to the argument that no one should be punished for behavior, however appalling or illegal, that happened so long ago.

Of course not. That would imply philosophical underpinnings that lead to consistency, and the Ginsburg nomination, along with the Thomas hearings and the current Kavanaugh standoff, illustrate exactly the opposite of that.

As a society, we have not yet resolved the question of how responsible any one of us is for our past. It is a question raised not only by Supreme Court hearings but also by the role and purpose of prisons, the rights of former felons (including the right to vote) and whether minors can be sentenced to life without parole. Rather than a broad social consensus on where the line might be — at the statute of limitations? the age of majority at 18? the time the brain reaches full maturity, at around age 26? evidence that a person has changed? suspicion that they haven’t? — we should, as a society, decide all these things. They are, however, tough questions, and require both thought and compromise, meaning we are further from answers than we been in generations.

In the absences of moral lessons learned, our politicians, therefore, look to political ones.

Ginsburg withdrew not because his long-ago drug use made him unfit for the court, but because it made his nomination untenable for the sitting president. Thomas was approved in part because some senators feared being accused of racism by rejecting a black man more than the consequences of being accused of sexism by disbelieving a woman’s allegations of harassment.

And Kavanaugh? Whether he is confirmed to the court will probably have little to do with what he did or didn’t do in high school. It will not depend on whether senators believe him or his accuser, or whether they agree that an individual’s youthful behavior should or should not be held against him or her. It will be about each senator’s calculations — most particularly those of Sens. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, and Susan Collins, R-Maine — of the political cost of believing either of those things.

Which is more important, getting this conservative seat on the court or risking voter reprisal in November? Which lights up the switchboard more, the #MeToo message that women should be believed, or one that Politico attributed to an unidentified White House adviser: “If somebody can be brought down by accusations like this, then you, me, every man certainly should be worried. We can all be accused of something.”

It will be politics, not truth or bedrock questions of right and wrong, that will be the deciding factor. And the Senate will kick the philosophical can down the road so some form of the same questions can be asked of the next nominee.

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court: