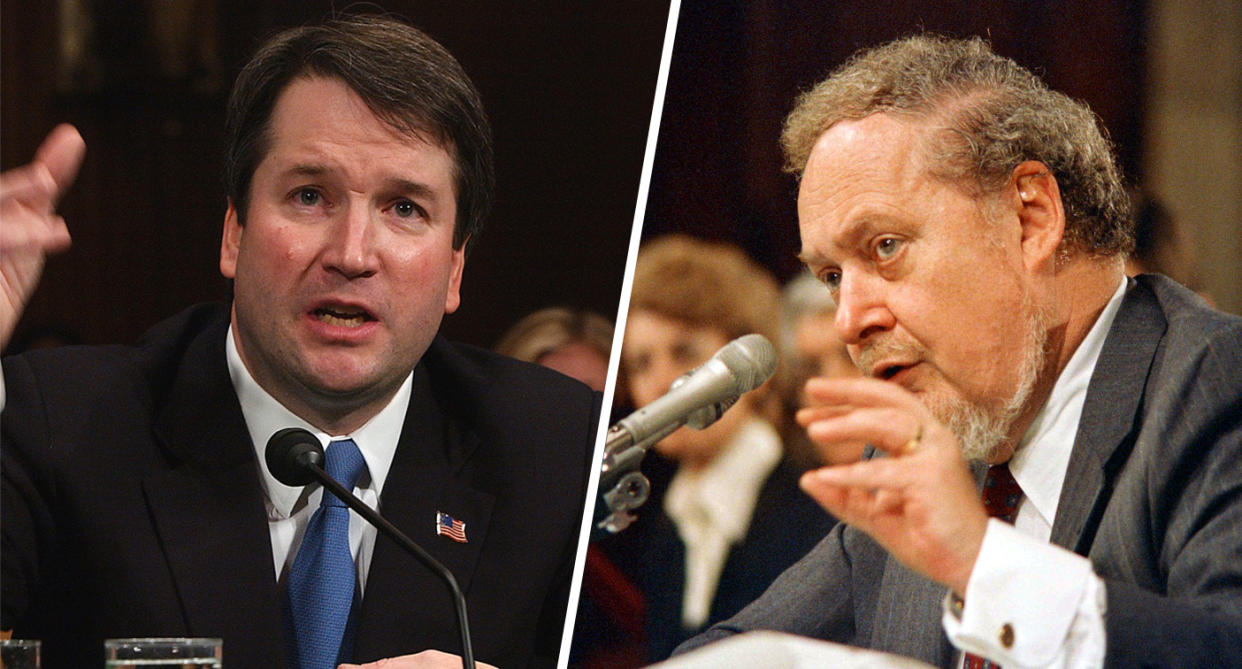

Can the Democrats do to Brett Kavanaugh what they did to Robert Bork?

WASHINGTON — The nomination of Robert H. Bork to the U.S. Supreme Court died on the afternoon of Friday, Sept. 18, 1987. The blow was delivered inadvertently by one of his supporters on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Wyoming’s Alan K. Simpson, on the fourth day of hearings for the Yale Law School professor and D.C. Circuit Court judge.

This was the question that Simpson posed, the question that sank Bork and changed the way modern-day judicial nominees approach the task of stating their views before the American people: “Why do you want to be an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court?”

Bork said he had spent his life in “intellectual pursuits in the law” and that serving on the Supreme Court “would be an intellectual feast.” This was an honest answer, and also a disastrous one, confirming the widely held suspicion that Bork was an elitist who did not understand or care about the concerns of ordinary Americans or how those concerns would be addressed in a court of law. The Senate Judiciary Committee, controlled by Democrats, voted against Bork 9-5. That made the full Senate vote a foregone conclusion; only 42 members of that chamber would vote for Bork, a major defeat for President Reagan.

Reagan eventually nominated — and the Senate confirmed — Anthony Kennedy to the position he had wanted Bork to fill. Kennedy served for the next 30 years. Having been nominated by a Republican president, he disappointed some and surprised others by sometimes siding with the court’s liberal bloc, his status as the court’s “swing vote” so well known that lawyers tailored their arguments to him directly. Kennedy retired in late June, and President Trump appointed D.C. Circuit Court Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the seat that was once supposed to be Bork’s.

Tuesday marks Kavanaugh’s first day of testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee. There are obvious parallels to the circumstances when Bork trooped up Capitol Hill for his first day of hearings on Sept. 15, 1987. A Republican president, in this case Trump, is promising to install a generations-long majority on the Supreme Court. Democrats have promised to stop him. But they lack the Senate majority they had in 1987. What they do have is public opinion on their side: Kavanaugh is the least popular Supreme Court nominee in recent history, with only 37 percent of Americans wanting him seated on the highest court in the land. The last nominee to elicit so little enthusiasm? Robert Bork.

The question now is whether Democrats can do to Kavanaugh what they did to Bork and prevent Republicans from turning the Supreme Court into a conservative redoubt immune — at least until the next vacancy — to changes in prevailing political attitudes.

Veterans of the Bork fight say that will be difficult, though not impossible, to accomplish.

Mark Gitenstein was chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1987, which was chaired by Joe Biden, then a Democratic senator from Delaware. Gitenstein, who later wrote about the Bork nomination in the book “Matters of Principle,” believes that Democrats can sink Kavanaugh’s bid not by focusing on specific issues — access to abortion, for example, or labor rights, both of which Kavanaugh views skeptically — but by depicting him as broadly antithetical to what most Americans stand for.

“If I were on that committee I would want to be convinced that Kavanaugh will not be part of a majority which will prohibit a future Democratic Congress and Democratic president from reversing the rollback the Trump administration has undertaken in workers’ rights, consumer rights, civil rights and the environment,” Gitenstein told Yahoo News.

“I fear,” he continued, “Judge Kavanaugh has a very narrow view of the power of Congress to enact legislation in these fields and of the administrative agencies to implement it. So even if President Trump is rejected by the voters in 2020,” he will have installed the “critical fifth vote on the Supreme Court that will preserve his legacy for a generation.”

Efforts to paint Bork as an extremist began less than an hour after Reagan announced the nomination, when Sen. Ted Kennedy, the liberal lion from Massachusetts, took to the Senate floor, where he offered a legendarily vivid picture of Bork’s America as a “land in which women would be forced into back alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists would be censored at the whim of government, and the doors of the federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is often the only protector of the individual rights that are the heart of our democracy.”

That proved a compelling opening shot, but Gitenstein believes that it was Biden’s questioning of Bork two-and-a-half months later that turned the American people against the nominee. “In that questioning Biden clearly established that Bork had a very narrow view of the Constitution and that he did not believe a right, such as the right to privacy, existed unless it was explicitly written into the Constitution,” Gitenstein said. Biden was especially effective in teasing out Bork’s views on Griswold v. Connecticut, which overturned a state law restricting the use of contraceptives. Bork attempted to stake out a nuanced position but ended up giving the impression that he would have the state intrude on matters of the bedroom.

Nan Aron, who founded the legal activism group Alliance for Justice, which was among the leaders in the anti-Bork movement, credits Howell Heflin, a conservative Democrat from Alabama, for managing to effectively portray Bork as an elitist. The slow-speaking Southerner noted that Bork had once been fond of socialism and, much more recently, had moderated his extreme positions to make them suitable for a potential Supreme Court nomination. “I wish I was a psychiatrist rather than a lawyer and member of this committee to try and figure out what you would do if you get on the Supreme Court,” Heflin said, to devastating effect. He would come to cast a crucial vote against Bork.

Simpson, the Republican from Wyoming, would be one of five members of the Judiciary Committee to vote for the nominee (another was Chuck Grassley, the Iowa Republican who today chairs the committee). But Nikki Heidepriem, an attorney and Democratic political consultant who worked with Alliance for Justice on the Bork nomination, believes that Simpson’s seemingly innocuous question about why Bork wanted to be a Supreme Court justice was what unraveled the Bork nomination. The “intellectual feast” response implicitly made Bork a character in the story Democrats wanted to tell about him, that of an out-of-touch Yale Law School professor — a literal graybeard — who cared far more about the law’s abstract intricacies than its real-life applications.

Kavanaugh does not come to Capitol Hill with nearly the intellectual pedigree of Bork: His decision are straightforward, written in ways that strongly suggest he was planning his own political future as he supposedly considered the law with dispassion. But he has the same Yale pedigree and decades of deft career management that took him from a role in Kenneth Starr’s investigation into Bill Clinton’s personal behavior to staff secretary for George W. Bush to a coveted seat on the D.C. Circuit Court. An argument could easily be made that he has just as little understanding of how ordinary Americans experience the law as Bork did.

Whether Democrats can effectively make that argument is the critical question. Aron of Alliance for Justice said that “after Bork, the playbook changed completely,” with nominees heavily coached by the nominating party and taught to avoid any controversy by disingenuously alluding to settled law. Kavanaugh has done just that in his not-especially-reassuring assurances about Roe v. Wade. “With Brett Kavanaugh, that playbook is very much in use,” Aron said, with the “added page” of 100,000 pages of Kavanaugh’s records that the Trump administration has withheld from scrutiny.

Unlike Bork, Kavanaugh is a consummate Washington insider: His father was a cosmetics lobbyist, and he was raised in the tony inside-the-Beltway suburb of Bethesda before heading to New Haven. The political game that Bork found so difficult to play comes practically as second nature to Kavanaugh.

“My sense is that Judge Kavanaugh has paid great attention to preparing for this moment,” said Heidepriem, “including his press conference listing the significance of women in his life from his mother, to his wife to his daughters,” a reference to the announcement of his nomination at the White House. Kavanaugh opened those remarks by preposterously praising Trump for his respect for the judiciary and by suggesting that Trump had deliberated more thoroughly in his Supreme Court selection than any president in American history. This show of obsequy may have endeared Kavanaugh to Trump, but it also could harm him with the Senate, which may not look kindly on a nakedly ambitious lickspittle.

Heidepriem added that “the threat to our constitutional democracy is far, far greater today than it was during the confirmation of Judge Bork. That threat is only heightened by the rapidity with which President Trump has filled federal court vacancies.” And while Supreme Court justices historically have drifted to the left during their tenures, Kavanaugh comes from a pre-screened Federalist Society list from which Trump has agreed to pick his Supreme Court nominee. Shows of genuine judicial independence have been rare. Drift is unlikely, unless it is even further right.

Unable to delay the confirmation hearings until the next Senate is seated in January, with the potential of a Democratic majority, the Democrats will have to win the fight in September. It’s not an easy proposition, but not an impossible one. “He’s decidedly unpopular person. He’s underwater with the public,” said Neera Tanden, president of the liberal think tank Center for American Progress. She noted that Kavanaugh has “unusual views on presidential power,” namely a deference to the executive branch that seems out of step with constitutional checks and balances. What would he do if the Supreme Court were forced to grapple with the potential fallout from Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian involvement in the 2016 election and potential obstruction of justice on the part of Trump? Would Kavanaugh recuse himself? And if he didn’t, would he be guided by principle or politics?

Tanden said Democrats “are not going to fall for the non-answer” when it comes to Kavanaugh’s positions, either on presidential power or contentious issues like the Affordable Care Act and access to legal abortion.

One senior adviser to a leading Democrat in the Senate told Yahoo News that staffers have been poring over transcripts of the last 40 years of Supreme Court nominations, trying to learn exactly how such battles were won or lost. In this case, the battle will be won by keeping Midwestern Democrats in line and attracting at least one Republican, probably Lisa Murkowski of Alaska or Susan Collins of Maine, who at least nominally support abortion rights. Not an easy task, the staffer acknowledged, but Republicans might be claiming victory a little too soon.

The adviser said the hearings do not need to produce a “gotcha” moment, only to foster the idea that Kavanaugh is so much a Republican insider that he stands outside the mainstream. He said Democrats plan to attack Kavanaugh’s integrity by accusing him of lying to the Senate in 2004 and 2006 about the Bush administration’s use of warrantless wiretapping and extrajudicial detentions. The Democratic staffer added that for all the talk of Roe, Kavanaugh truly showed his hand on reproductive rights when he praised Antonin Scalia’s dissent in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, the 1992 Supreme Court decision governing how states could and could not regulate abortion. Kavanaugh was similarly approving of Scalia’s dissenting vote in Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 marriage equality ruling.

And there is, of course, the issue of presidential power. Many believe that Trump selected Kavanaugh based on a 2009 Minnesota Law Review article that seemed to suggest a sitting president should be protected from prosecution, so as to avoid distracting him from his duties. “The President should be excused from some of the burdens of ordinary citizenship while serving in office,” Kavanaugh wrote. With his preternaturally acute sense of self-preservation, Trump could have seized on that line. Democrats may well do the same.

“The candidate is flawed, and the process is reprehensible — no one can disagree with that,” lamented Aron, who has won and lost plenty of fights in her long career as a judicial activist. With Kavanaugh, as with Bork, there are plenty of arrows in the quiver. The question is who will wield them, and how effectively.

“All we need,” Aron said, “is a few courageous Senators.”

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court: