New Jersey House race tests the limits of the backlash against Trump (and Pelosi)

MEDFORD, N.J. — It’s the kind of thing candidates always say: “This is the single most important election that our district has ever been a part of.”

So when Democrat Andy Kim, the 36-year-old political novice challenging Republican Congressman Tom MacArthur in a swath of South Jersey that stretches from the Philadelphia suburbs to the Jersey Shore, came to Pennsauken Township’s Double Nickel brewpub last week, stood atop a table, and said just that, most reporters likely would’ve dismissed it as the usual campaign rhetoric — a familiar hyperbole meant to fire up the base.

The same reporters might have yawned when Kim — baby face, black glasses and dark fitted suit — went on to insist, to the cheers of 300 or so supporters scarfing down Wing King pizza and pulling at pints of Lawn Surfer IPA, that “the whole world is watching us” because “they know that what happens on Nov. 6, and who controls Congress, and what direction our country takes after that could very well — will very well — come down to who wins New Jersey’s Third Congressional District.”

“I’ve never seen anything like this, having grown up and spent my whole life [in] our humble district,” Kim added, his soft Philly accent rebounding off the taproom’s high industrial rafters. “Because of you, we have made this one of the most powerful political forces in the entire nation.”

By that point, most reporters probably would have been rolling their eyes.

But like Kim, I grew up in the Third District. In fact, I grew up there at the exact same time as Kim. He’s from Marlton. I’m from Medford, one township east. He graduated from high school in 2000. So did I. Within minutes of meeting, we realized we used to play soccer against each other. Kim’s first job was serving coffee at the Barnes & Noble where I spent far too many adolescent afternoons scouring British music magazines. His humble district is my humble district.

And so I can report that Kim’s line about the sudden importance of NJ-03 and how he’s never seen anything like it isn’t a line at all. It’s the truth. As kids, national politics wasn’t a big deal in our part of New Jersey, where local schools, local businesses, local farms and local sports always seemed to matter more than whatever was happening in Washington.

Now that’s changed. According to the latest polls, MacArthur and Kim are tied at about 45 percent each, with roughly 10 percent undecided. The nonpartisan experts at the Cook Political Report consider the race a tossup — one of the 30 or so that will determine whether Democrats retake the House. Kim’s ground game is perhaps the most extensive in NJ-03 history, with more than 700 active volunteers and 125,000 doors knocked on. And the money is pouring in; last quarter, Kim raised $2.3 million, shattering the district record, and outside groups have dropped another $6.5 million to date, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Earlier this month, I spent the better part of a week revisiting my old haunts and chatting with as many voters as I could. Kim might have been exaggerating when he claimed the rest of the world was already watching his matchup with MacArthur. But if we want to understand this year’s midterm elections — the deeper forces at work, and the shifts they could set off — there may be no better contest to keep an eye on.

***

NJ-03 is an odd place. Wrapped like a ribbon around New Jersey’s waistline, it’s really more like two, or even three, districts in one. The western half belongs to Burlington County, and the further west you go toward Philadelphia, the more suburban it gets; think multilane highways flanked by car dealerships, strip malls, T.G.I. Fridays and Targets, with cookie-cutter 1970s and 1980s developments spread out behind them. Move toward the middle of the district and the generic big-box sprawl gives way to larger lots, cedar-water lakes, flat farmland, and, eventually, the million-acre, nearly uninhabited expanse of the Pinelands Natural Reserve, home to Fort Dix and McGuire Air Force Base. Cross into Ocean County and civilization returns, this time in the form of exurban retirement communities, shoreline vacation spots and the closest thing the district has to a metropolis: Toms River and Lakewood (combined population: 180,000).

The district’s political geography is just as varied: largely Democratic in the east, near Philly; decidedly more Republican as you head toward Toms River; purple in between. Overall, NJ-03 leans slightly GOP: Republicans have represented the region in Congress for decades, with only one brief Democratic interregnum, and most local lawmakers are Republicans too.

But the key word here is “slightly.” The Cook Political Report gives NJ-03 a Partisan Voting Index score of R+2, which means the district typically performs about 2 percentage points more Republican than the nation as a whole. That’s close enough that a Democrat can win, given the right campaign and the right conditions; Barack Obama did it twice, in 2008 and 2012. It’s also close enough that voters can easily revert back to a Republican — as they did in 2016 when they made NJ-03 one of only 21 districts nationwide to flip from Obama to Donald Trump.

“It’s not a particularly cohesive district,” explains Prof. Brigid Harrison, an expert on Garden State politics who teaches political science at Montclair State University. “You have some relatively affluent, socially liberal communities, but also a hodgepodge of relatively working-class rural areas that were drawn to Trump.”

It is this lack of cohesion, however, that makes NJ-03 such a revealing lens through which to view the coming election. If the major question of this year’s midterms is whether white, college-educated suburban moderates, particularly women, will defect from the president in sufficient numbers to ensure his party’s defeat — or whether less-educated rural whites, particularly men, will turn out in sufficient numbers to preserve Republican rule — then where better to look than a district that’s 76 percent white; evenly and sharply split between rural, suburban and exurban electorates, and already inclined to vacillate between Team Obama and Team Trump?

The candidates themselves also help clarify these dynamics. MacArthur is about as good an avatar for Trump as you could expect to find in a swing district. Like Trump, he’s a fairly recent convert to politics: he was elected councilman in Randolph, N.J., in 2011, and then mayor in 2013. He moved south to the Third District in 2014 to run for Congress. Before that, MacArthur was in business, rising through the ranks of the insurance industry to become chairman and CEO of York Risk Services Group. He is also wealthy — one of the 20 richest lawmakers on Capitol Hill, with an estimated net worth of $64 million.

At first, MacArthur cut a centrist figure in Congress, earning a reputation as one of the more bipartisan and even moderate members of the House. But the rise of Trump has clouded that perception. In 2016, MacArthur was the only Republican member of New Jersey’s House delegation to attend Trump’s nominating convention in Cleveland; since 2017, he has voted with the president 94.6 percent of the time, according to the data journalists at FiveThirtyEight, which is 15.4 percent more often than one would expect based on the voting patterns of his constituents, and far more often than any other Republican running for reelection in New Jersey.

Two of MacArthur’s votes stand out. One was for Trump’s tax-cut bill, which MacArthur supported despite a cap on state and local tax deductions that will effectively raise taxes on many New Jersey residents. (The rest of the Garden State’s GOP House delegation opposed the legislation.) The other was for the American Health Care Act — aka the GOP’s Obamacare repeal bill, which no other New Jersey House Republican supported.

MacArthur assumed a lead role in both skirmishes, negotiating to preserve a $10,000 allowance for property-tax deductions and resurrecting the near-dead Obamacare repeal bill with an amendment — since dubbed the “MacArthur Amendment” — that mollified conservatives by permitting states to waive the law’s essential-benefits requirements, thus weakening its protections for people with preexisting conditions.

The backlash in NJ-03 was swift and severe. “You are the greatest threat to my life!” one constituent shouted at a marathon four-hour town hall in Willingboro on May 9, 2017. (The man’s wife survived cancer; his two children each have preexisting conditions.) “You are what keeps me awake at night.”

Two weeks later, MacArthur was forced to resign as co-chairman of the Tuesday Group, a coalition of moderate Republicans, amid a revolt over his role in the health care compromise. The following month, Kim announced his candidacy.

On paper, Kim reflects the last man to lead his party — Obama — in much the same way MacArthur reflects Trump. For one thing, he’s not white; as the son of a geneticist and a nurse who emigrated from South Korea, Kim was a distinct minority growing up in Marlton, where even today Asian-Americans comprise less than 5 percent of the population. Kim also spent six years serving the former president before entering politics: he started in 2009 as a career employee at the State Department, working on Iraq policy; then was a diplomat advising Gen. David Petraeus and his successor, Gen. John Allen, in Afghanistan; and finally served as Iraq director for Obama’s National Security Council.

Kim’s time in the Obama administration capped a rapid rise through the millennial meritocracy. His résumé, like Obama’s, is studded with elite academic achievements: two years at the ultra-selective “cowboy monastery” (Kim’s words) of Deep Springs College; two years at the University of Chicago, volunteering with a citywide homeless charity, and three years as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University, where he completed a Ph.D. dissertation on U.S. policy in Iraq. In college and then again after his stint in government, Kim gravitated toward grassroots, Obama-esque activism, first as an Iraq War protestor and more recently as the founder of RISE Stronger, a resistance group launched in late 2016 “with the mission to monitor Trump.”

In a sense, then, MacArthur’s strategy is straightforward: downplay his Trumpian side and stress his centrist bona fides while being careful not to alienate his district’s many MAGA fans. “I’ve been named one of the most bipartisan members of Congress every year in office,” the congressman says in a recent ad. “Andy Kim is running to protest Trump. I’m running to represent you, whether you like Trump or not.”

At the same time, MacArthur and various outside groups have attempted to define the relatively unknown Kim before he can define himself, running attack ads that characterize him as a carpetbagging D.C. “insider” and Nancy Pelosi liberal who has inflated his résumé and exaggerated his overseas service. Some have even flirted with racism, characterizing Kim as “not one of us” and declaring that “there’s something real fishy” about him in a faux-Asian, “chop suey”-style font.

Kim’s strategy is trickier. The challenges he faces are the same ones facing other Democratic insurgents — many of them young, female and/or people of color — in swing districts nationwide: How progressive can he afford to be? How anti-Trump? And what’s the proper balance to strike between identity politics and pocketbook appeals?

***

Back in South Jersey, I quickly discovered that Kim is not running the kind of campaign that garnered Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez so much attention earlier this year. Cautiously centrist is the phrase I would use.

Kim’s mailers don’t mention the word “Democrat”; instead, they describe him as “an independent leader.” His ads emphasize “service,” claiming that he’s “a kid from Marlton who became a national security advisor for Republican and Democratic presidents,” as photos of George W. Bush and Obama flash onscreen — even though Kim’s entire experience under Bush amounts to four months as an intern at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and five months as a entry-level conflict management specialist in the agency’s Africa bureau, according to the Washington Post’s Fact Checker column, which awarded Kim two “Pinocchios” for indulging in “a classic case of résumé puffery.”

“It was the first job that I had,” Kim explained in a recent debate. “I was not trying to equate that job with the last job I had … under President Obama. What I was trying to convey to the people of this district is that I’m someone who deeply believes in bipartisanism.”

Even in person, the earnest, mild-mannered Kim is relentlessly on-message — his message bearing little mark of the gravitational forces currently pulling many other Democrats to the left. One afternoon, I visited Kim at his campaign office in Willingboro, the district’s most heavily African-American (and as a result, Democratic) town. Rainbow-colored “Disarm Hate” placards hung in the storefront window; inside, the walls were papered with handmade signs that read: “No Wall No Ban Yes ACA” and “Protect Mother Earth.”

(MacArthur, who rarely holds public campaign events, was raising money with Vice President Mike Pence in New York and Rep. Jeb Hensarling in Texas during my visit. His campaign did not make him available for an interview.)

Kim and I slipped into an empty office and sat down; he reached for bag Haribo gummies. Over the next 45 minutes, I asked a bunch of questions about the progressive policy ideas now animating his party. Kim, however, did not seem to feel strongly about any of them. Asked whether he supports Medicare for All, for instance, he demurred. “Where I’m focused right now is stopping the [Republican] erosion [of Obamacare],” he said. “I’d like to see … thorough research and analysis on all the different plans that are out there. But right now, the severity of the [Republican] threat is something that takes up all of my time.”

The same went for impeachment proceedings against Brett Kavanaugh, which some House Democrats have promised to pursue. “I haven’t thought about it yet,” Kim insisted. It’s not exactly accurate to call Kim a moderate, because it’s not like he rejected any of the policy ideas I ran by him, from a federal jobs guarantee to free college tuition. He simply deferred judgment, again and again.

“I think the party can have a lot of decisions and discussions about what it can do after Nov. 6, depending on what happens,” he said. “I want to make sure that we don’t get ahead of ourselves.”

As far as I could tell, there was only hot-button Democratic debate that Kim was willing to wade into: the internal dispute over whether Nancy Pelosi should continue to lead House Dems if they regain control of the chamber. Kim’s answer is no, a stance he shares with many other Democrats looking to distance themselves from her reputation as a “San Francisco liberal.” But when I asked why, Kim couldn’t cite any particular grievance.

“It’s not just about her,” Kim explained. “There’s just been this hyperpartisanship that has taken over. People in this district don’t want more of the same. They’re hoping for new leaders that approach politics differently.”

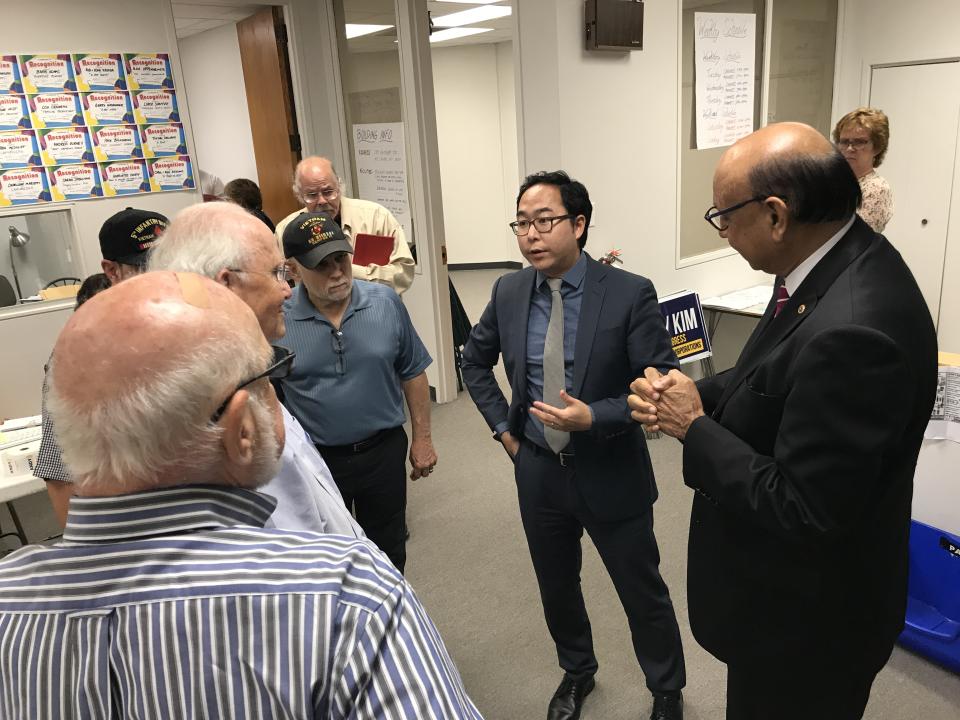

The day I arrived in New Jersey, I spent five hours shadowing Kim on the campaign trail, including two hours casually conversing with the candidate and his guest of honor, Gold Star father Khizr Khan, aboard the repurposed school bus he rented for the occasion.

What struck me most, in this Era of Endless Trump, was how rarely Kim mentioned Trump: only twice, and even then only in passing. During a small gathering with a dozen local war veterans at Kim’s campaign headquarters in Mount Laurel, a man with a mustache and a black Fifth Infantry Division baseball cap lamented the president’s five draft deferments. Kim didn’t take the bait, noting instead how he served as a Senate Foreign Relations Committee fellow under “moderate Republican Richard Lugar,” and how his “career as someone who’s willing to work with under both Republicans and Democrats shows [he’s] a pragmatic and strategic person.”

In part, Kim lucked out with his opponent. At the Double Nickel event, and again at a second rally later that evening in the backroom of Toms River’s Rinn Duin brewery, Kim didn’t bother to knock Trump. He didn’t have to. Instead, he could stir up the same animus — without conveying the same sort of reflexive partisanship — by simply railing against MacArthur’s locally toxic (and decidedly Trumpian) apostasies on health care and taxes.

“Unlike most New Jersey Republicans who kind of walked fine line between placating their relatively liberal constituents and toeing the line for their party, Tom MacArthur was someone who really championed big parts of the Trump agenda,” says Brigid Harrison of Montclair State University. “In many ways, then, this race is really a litmus test for how that message plays for Republicans.”

Yet in his own way Kim has made it a litmus test for Democrats as well. At a time of roiling ideological divisions, how safe can their candidates play it? For now, Democrats can take the anti-Trump tide for granted; it’s likely to propel them into power, at least in the House. But how will they navigate between progressive passions and pragmatic promises when they get to Washington? At what point does caution begin to look like inauthenticity?

Kim seems to recognize the risk of this approach. Near the end of our interview, I asked him why both Trump and Obama won this particular district.

Kim paused before answering. “They were outside the mold,” he eventually said. “There’s a lot of talk about this word ‘authenticity’ in politics, right? The candidates who resonated here were very authentic to who they were. And I hope to be one of them as well.

“I’m trying to approach these problems that we’re dealing with — health care and other issues — in the way that I’ve approached all the problems in my life,” Kim continued. “And that’s why I want to make sure that we proceed deliberately and carefully, because in national security, when lives are on the line, you’ve got to make sure that you are being precise in every step.”

Whether the voters of NJ-03 buy this argument — that for Kim, caution is authenticity — remains to be seen. A few days later, MacArthur released an ad claiming that Kim’s involvement with the run-of-the-mill resistance group RISE Stronger — its website since wiped from the internet — proves he’s not a “bipartisan moderate” but rather a “partisan warrior.” The accusation wasn’t so much that Kim is “far left” or “far out,” even though those were the words that appeared on screen. It was that Kim isn’t who he claims to be — that he isn’t authentic.

In a district full of people who pride themselves on telling it like it is, this sort of thing matters. After the Rinn Duin rally, Kim took one last sip of Lawnmower pale ale and climbed into a car with his wife for the long drive back to their home and two young kids. I boarded the bus. As the pinelands passed outside the window, I asked Kim’s campaign manager how they planned to edge out MacArthur. The public polls, he said, pretty much had it pegged. Kim was leading by double-digit margins in Burlington County; MacArthur was leading by the same amount in Ocean County. In the end, it would all come down to what he called the “M towns” — the purple strip of municipalities (Medford, Marlton, Mount Laurel) on the border between dense blue suburbia and the red forests and farms to the east. Mobilize the “M” towns, and you’ll probably win on Nov. 6.

The next day, I took a ride through Medford, my childhood home. I drove by Kirby’s Mill (“Feed for Every Need”) and Harriet’s heating oil. I drove by the fruit and vegetable farm where we used to buy cider doughnuts and the lakes where we canoed in summer and skated in winter.

I thought about the people I knew as a kid: most of them Catholic, a few of them Jewish, almost of all them what I later learned to call “white ethnic” — Italian-Americans, Irish-Americans, German-Americans. Their grandparents had emigrated to Philadelphia; their fathers had started small, hands-on businesses like lumber yards and landscaping companies; they had attended college, the first in their family, and married and moved out to Medford for the space and the schools. Almost none of them were doctors or lawyers or financiers. Some were teachers or social workers. Many started small businesses of their own. They had a little more money than the average American, maybe, and slightly more education. But they were still blue-collar in spirit and style — Philly types, underdogs. Most of all — and I know I’m overgeneralizing, but this is how I remember the personality of the place — they didn’t tolerate any BS.

On a whim, I took Route 206 to Pic-a-Lilli Inn, an old roadhouse the edge of the Pine Barrens where my high-school clique used to go every Wednesday night for all-you-can-eat wings. It was 3 o’clock in the afternoon — the start of happy hour. I ordered a “lager” and struck up a conversation with the bartender, Carol. Her T-shirt read “you can’t buy happiness but you can buy wine and that’s kind of the same thing.” Talk quickly turned to politics.

By that point I’d already sounded out a dozen or so local voters in diners at Kim events — many of them the very same independent-minded suburban women who pollsters insist will decide the election. Their views ran the gamut. Susan Woodend of Medford Lakes — a Spanish teacher who (small world) turned out to be pals with the mother of my high-school girlfriend — said that she was a registered Republican who’d hit a “tipping point” with the “misogynistic” Trump. Now she was knocking doors for Kim, something she’d never done before.

On the other end of the spectrum was my close childhood friend, now a local health-care professional with Republican leanings. After dinner she told me that while she considers Trump a clown, the Democratic Party ultimately just wants to raise her taxes to pay for programs that “don’t work,” like food stamps. She already has so much on her plate with work and kids, she sighed; chances are she wouldn’t be bothering to learn more about this year’s congressional candidates, or casting a ballot.

But Carol the bartender was the first voter I’d met who seemed to capture the place I’m from — “bumf***,” she called it — in all its no-bull complexity and contradiction. As a “Friends” rerun played on the TV behind her, Carol explained that even though she’s a registered Republican, and even though she sometimes “feels bad for Trump, the way he gets s*** no matter what he says,” she refused to vote for him in 2016. “The guy’s a maniac — an egomaniac,” she said. Now, two years later, the president had done nothing to change her mind: “I want the Democrats to win in November, just as a kick in the teeth to Trump.”

Despite all that, Carol — who declined to share her last name — still wasn’t sure whether was willing to personally kick any teeth by voting for Andy Kim. A journalism major in college, she’s now what a campaign consultant would call a “high-information voter.” She constantly refreshes ABC News on her phone. She has strong opinions about Christine Blasey Ford, the academic who accused Brett Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her when they were teenagers. (“Come on,” she scoffed. “A guy can’t even look at a girl anymore without getting charged with rape.”) And she was intimately acquainted with all of the NJ-03 attack ads.

As a result, Carol had concerns about both candidates. “Kim talks about service in a way that makes it sound like he’s something he’s not — like he actually served in the military,” she told me. “MacArthur wrote the health bill. That just kills him.” Neither candidate had quite passed the South Jersey smell test — not yet.

Before I left, I asked Carol if there was any chance she would simply stay home on Nov. 6.

“Hell no,” she said. For her, the decision will come down whether she believes that Kim is who he says he is — a “kid from Marlton” who’s “different” than other Democrats. My sense is she’s not alone.

_____

Read more Yahoo News midterms coverage:

Indiana Sen. Donnelly backs border wall in new ad, and GOP pounces

In Senate race, GOP Rep. Blackburn accuses her opponent of being a Democrat

Will Rick Scott’s playbook withstand a potential Democratic wave?

Facing doubts from women voters, Tennessee’s Phil Bredesen opens up about an assault on his wife