'You never forget the sight.' Tinton Falls WW2 veteran recalls liberating Nazi death camp

TINTON FALLS – In Allan Ostar’s apartment, there is a red box in a closet. Inside the box sits a belt buckle bearing the words “Gott Mit Uns.”

That’s German for “God is with us.”

Ostar pulled the buckle off of a dead German soldier when, as a U.S. Army private, he helped liberate the notorious Dachau concentration camp at the end of World War II. That liberation, the culmination of a brutal journey, took place 79 years ago today.

“How could any human being believe that God was with those who would commit these horrible crimes to humanity?” Ostar said last week.

He’s 99 years old now. For years, he brought the buckle to his speaking appearances at schools, houses of worship, and places like Brookdale Community College’s Center for Holocaust, Human Rights & Genocide Education, where he once set a Holocaust denier straight.

“Well, I was an eyewitness,” he said.

Ostar doesn’t get around as much anymore, though he’s still sharp of memory and a good storyteller. His story needs to be heard before the Greatest Generation passes fully into history.

Socks in the armpits

Ostar grew up in Philadelphia and attended Penn State for a year before enlisting. The army trained him as a radio man and taught him how to drive – he’d never been behind the wheel before.

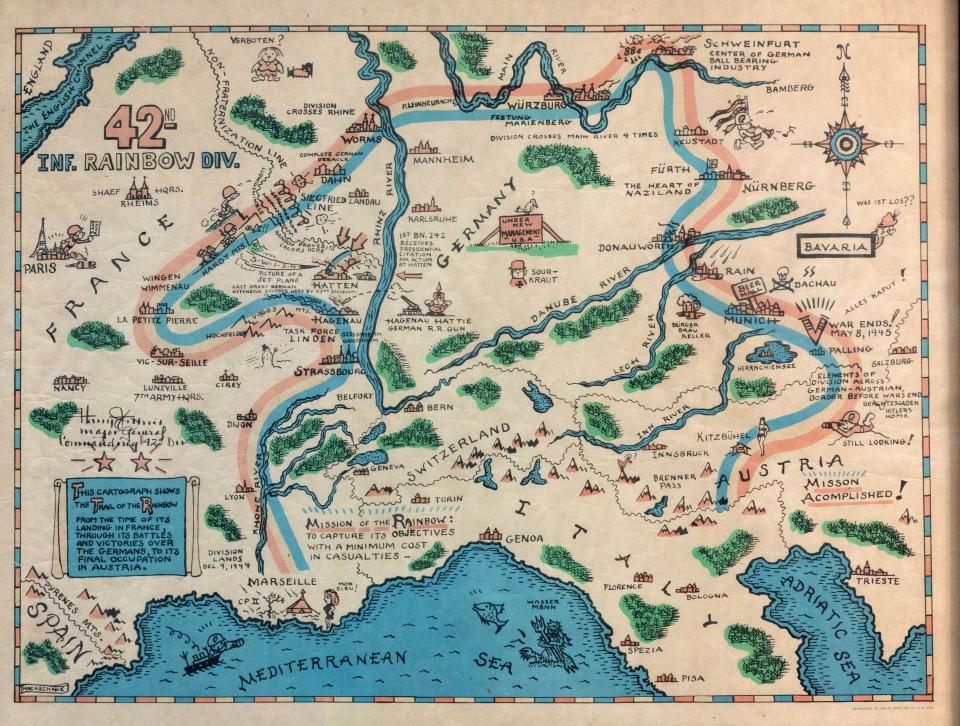

Sailing to Europe was rough – on his ship they crammed three men to a bunk, and seasickness ran rampant. He arrived in northern France in December 1944 and proceeded to fight his way across the continent with the 42nd Infantry Division.

“Trench foot” was common that winter – it was so cold, frostbite cost more than a few men their toes. Ostar preserved his thanks to advice from an officer who had served in Alaska: Keep an extra pair of socks stuffed in your armpits, which served as natural warmers.

Driving wasn’t much easier. Ostar nearly drove a jeep off a mountainside after he hit an icy patch, spinning the vehicle around. It slammed into the bedrock instead, earning a sharp rebuke from an officer who was more worried about the vehicle than its occupants.

During the bloody Battle of the Bulge, Ostar was sending radio communications from a tower and taking fire from four German tanks.

“We were a sitting target,” he said.

Ostar hung in there as long as he could – later, he was awarded a Bronze Star Medal for “outstanding courage and devotion to duty” that day. As he evacuated in a jeep riddled with holes from mortar shrapnel, tank destroyers manned by African American soldiers provided life-saving cover. It was a memorable sight, because the army was segregated, with Blacks usually assigned to non-combat duties.

“That was the first time we saw African American soldiers in combat,” Ostar said. “God bless them, they fought off the German tanks so I could get away.”

All of that was a prelude to the horror ahead.

'You never forget the sight'

On April 29, 1945, as Ostar approached the wrought-iron gates of Dachau, the enormity of the Holocaust hit him like an anvil.

“The first thing you saw and also smelled: a string of boxcars filled with dead or dying prisoners,” he recalled. “You never forget the sight of all those bodies.”

There were orders against feeding prisoners who were starved beyond saving – "we were told if you feed them, it will just kill them,” Ostar said. A few survivors he encountered wept upon the sight of American troops.

Beyond the death camp, Ostar participated in the pursuit of retreating German soldiers. At a nearby airfield he cornered a Luftwaffe commander, who handed his sword to the private as an act of surrender. Ostar still has the two-foot sword, unsheathing it last week to reveal a blade that remains razor-edged.

“He was not interested in fighting,” Ostar said of the commander.

In 1992, Ostar retraced his wartime path with his son John.

“ He always said: I want to see Europe in better circumstances – not from a muddy foxhole,” John Ostar said. “He wanted to make sure I saw Dachau.”

While they were at the camp, busloads of young German soldiers arrived.

“They bring every class (of new soldiers) to a concentration camp so they know the history, to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” John Ostar said. “It was impressive to see.”

A message to impart

After the war Allan Ostar finished his degree at Penn State and embarked on a distinguished career in higher education, serving as longtime president of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Among his legacies is the development of international student-exchange programs that continue to thrive on campuses around the world. In 1990, for his efforts in making college more accessible for veterans, he received the U.S. Department of Defense Medal for Distinguished Public Service.

As surviving witnesses of the Holocaust dwindle, there is a message he’d like to impart.

“We’ve got to find ways to resolve problems without resorting to violence,” he said. “You read about what’s going on in Israel, Gaza, Thailand, Africa – human beings are still fighting to kill somebody else.”

He is asked: If everyone saw what you saw, stacks of starved bodies of men, women and children, would there be more respect for human life?

“You would like to think so,” he said.

Jerry Carino is community columnist for the Asbury Park Press, focusing on the Jersey Shore’s interesting people, inspiring stories and pressing issues. Contact him at jcarino@gannettnj.com.

This article originally appeared on Asbury Park Press: Tinton Falls WW2 veteran recalls liberating Nazi death camp Dachau