Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generals

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Something extraordinary is happening in Myanmar, said Moe Sett Nyein Chan in The Irawaddy (Chiang Mai,Thailand): the nation formerly known as Burma is on the brink of witnessing an unexpected victory for the underdog.

When its notoriously brutal military – the Tatmadaw – overthrew the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi in February 2021, a "Spring Revolution" of armed protest movements swept across the country and have continued ever since. At the same time, a sizeable group of deposed MPs, mainly from Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, set up their own National Unity Government (NUG) in exile: it now has its own "People's Defence Force", and has been recognised by the European parliament as the legitimate government of Myanmar.

Spring Revolution 'gaining momentum'

Yet none of this initially fazed the generals: they ridiculed the resistance, boasting that they would "annihilate" the rebels. And the overwhelming expert consensus was that the military junta was simply "too strong to fall". Yet just over three years later, "the Spring Revolution is gaining momentum as it captures major bases and entire towns across the country".

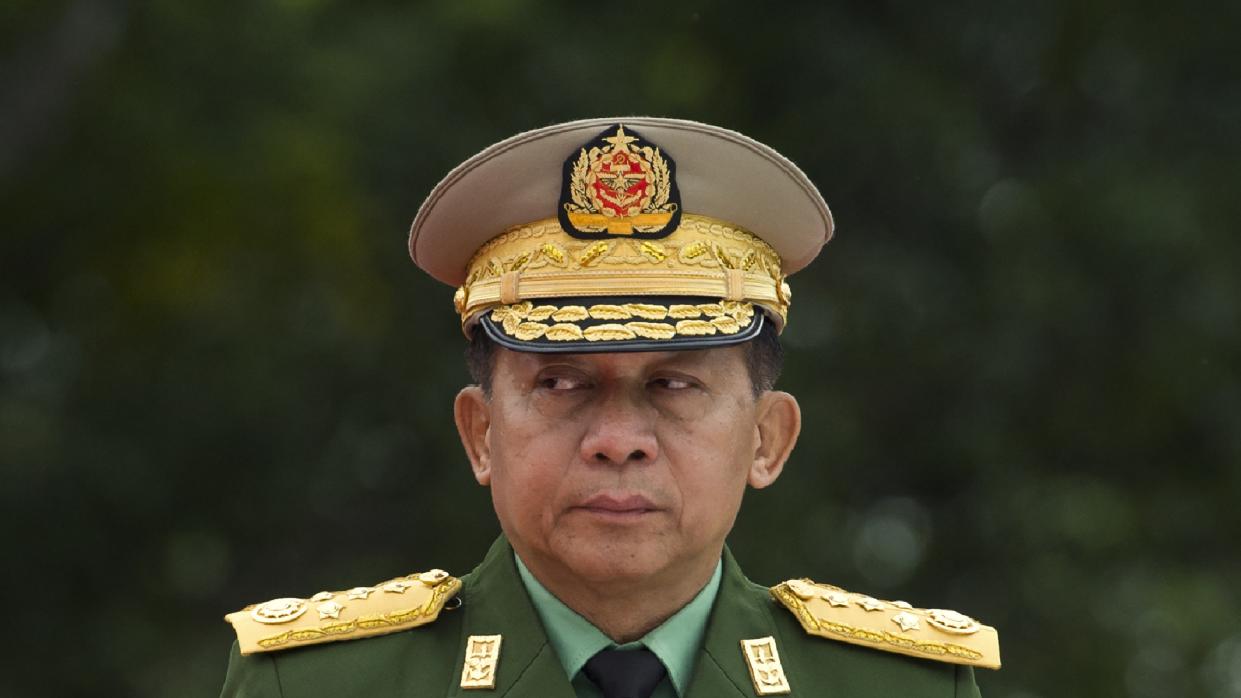

The junta is "now seeing its losses snowball", said Joshua Kurlantzick on the Council on Foreign Relations (New York). Since October, a blend of ethnic armies have joined forces to batter the junta in Shan State, in the north, seizing territory and encouraging mass defections. In the east of the country, Karen rebels have captured junta battalions and taken the border town of Myawaddy, opening a channel for arms and aid to be brought in from Thailand. And in a symbolic slap to the face of the junta, said Myanmar Now (Yangon), rebels have launched drone strikes on the supposedly secure capital, Naypyidaw, where the office of junta chief Min Aung Hlaing is located.

The rebels' strength – and weakness – is that their forces are composed of so many different groups, said The Economist. "Myanmar is hugely diverse": it’s home to some 135 ethnicities, whose rivalries were accentuated by the British imperial policy of pitting them against each other from the 19th century on. The fierce divisions between them endured after Myanmar gained independence in 1948, said Avinash Paliwal in Foreign Affairs (New York). Its governments have long been dominated by the majority Bamar group, and for decades minority militias have fought them in an effort to win more autonomy. Even now there are fears that the rebel NUG could revert "to the Buddhist- Bamar majoritarianism that characterised Aung San Suu Kyi’s rule".

The junta has tried to exploit such divisions, but as the army is held to be the vanguard of Buddhist-Bamar nationalism, and also horribly corrupt, its divide-and-rule strategy has failed. Instead, different sets of armed ethnic groups have united behind the common cause of toppling the junta, said Lorcan Lovett on Al Jazeera (Doha). The most powerful, the Three Brotherhood Alliance, has notched up unprecedented victories against the junta's forces. It still won't accept the NUG leadership, but at least for now it is prepared to work with it.

Junta's days 'numbered'

The generals aren't giving up easily, said Sven Hansen in Die Tageszeitung (Berlin). They've activated a law calling up all men aged 18 to 35 for military service, and all women aged 18 to 27. Yet so hated is the Tatmadaw that thousands of potential recruits have fled abroad or paid bribes to dodge the draft. Meanwhile, the war is exacting a high civilian toll, said Der Standard (Vienna). The UN estimates more than 2.7 million people are now displaced. There are even reports that Rohingya Muslims, so badly brutalised by the army that the International Court of Justice convicted Myanmar of mass murder in 2020, are being coerced into fighting on the front line and being used as cannon fodder.

Hard to know how it will all play out, said Avinash Paliwal. The junta is deeply divided: morale is low, and soldiers are defecting en masse. But like the junta, the resistance militias are steeped in the drug trade, yet another factor that imperils the newfound unity among them. If that unity does somehow endure, however, the junta's days may be numbered.