The last war reporter

“Don’t call yourself a war reporter.”

In a crisp blue suit and enormous corner office, an executive at a news network I once worked for scolded me as he leaned back in his chair and explained: The term doesn’t really exist as a job title. “It’s foreign correspondent.”

It was 2012 and I had just returned from an assignment in Syria as revolution tumbled into all-out war. I was still teetering back into office life after being smuggled into a rebel-held area of Syria, alone, where I filmed and documented the Bashar al-Assad regime’s crackdown on his people. It had been only 48 hours since I trudged across the border to Lebanon on foot, evading armed men to escape in the middle of the night, certain I was about to be shot in the back. Now I was facing a man in a suit. This was something of a debrief with management.

He was technically correct about what I called myself. Referring to oneself as a war reporter was not really the done thing. It was something looked upon as cringy, self-aggrandizing and only articulated by the naïve: those of us still filled with romantic notions of Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway holed up together in a battered hotel in 1930s Madrid covering the Spanish Civil War.

In that office, still in my 20s, I sat in quiet acquiescence. “Foreign correspondent” is the umbrella term for anyone reporting overseas from the publication or outlet’s home country. The reason the term “war correspondent” is unsatisfactory to many as a “beat” is that it is never an initial posting. Reporters are sent to dicey regions to cover whatever may happen.

“I was a foreign correspondent usually responsible for covering a region, who had to cover conflicts,” says Princeton journalism professor and former Washington Post correspondent and editor Keith Richburg, who spent decades reporting from places like Somalia, Liberia and Afghanistan. If uprisings, revolutions, riots and skirmishes slide into all-out war, those who stick around and function well find themselves called upon by editors the next time a story arises that needs the strange skills of working well amid chaos and danger. We become known in newsrooms and organizations as the person or people who can cover war.

Journalists have been running through besieged streets and peering out of foxholes for well over 150 years. Each time, their work has been “unprecedented.” Each war is different and the coverage of it new, as both the nature of conflict and funds of the media have evolved over the years. No such evolution, however, has been as rapid and transformative as in the last few years. Technology, access and cultural shifts all have changed the very nature of what a war reporter is. And, what it is not.

Vladimir Putin’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine brought war reporting back into the spotlight after years of international coverage languishing behind American politics and the Covid-19 pandemic. I had never known so many Americans to be gripped by overseas news, watching each night as they did in the first months of the war in Ukraine. That coverage was suddenly shattered by the war in Gaza, which has since thrust war reporting to center stage in a way not seen since the post-9/11 invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Yet, as the country watches and reads more on war in real time than it has in decades, the profession has changed dramatically, in some ways excelling, and, in others, struggling to survive at all. “The foreign correspondent is increasingly no longer foreign,” says Richburg. “They are a local.”

If you have an ax to grind you may as well be a party to the conflict. We all have our biases, but we try to leave them at home.

When the October 7th terrorist attacks happened and subsequent war broke out in Gaza, I was on the leafy campus of Princeton University. Teaching a class on war reporting, I had selected the greats of reporting’s past — from Orwell, Hemingway and Gellhorn in 1930s Spain to Edward R. Murrow in London’s blitz, Marguerite Higgins in Korea and Sydney Schanberg’s “Killing Fields” in Cambodia up to most recent reporting in the post-9/11 wars. I had for weeks been Zooming in class with field reporters in places like Ukraine. Suddenly, videos and images poured out of Israel and Gaza, much of it not from professional journalists in the early days. Never before has the replacement of foreign correspondents by local reporters been more stark … and more necessary.

Students came to class having read the news, but also having seen unsourced videos that had gone viral on Twitter and Instagram, asking if these were real. “Did you see this video?” had replaced, “Did you see that report?” My lectures on sourcing, narrative arc, access and humanity, finding great characters, and how to do strong interviews, seemed at once hopelessly archaic and quaint, and also all the more urgent.

As journalists attempted to keep up with the onslaught of social media commentary and content, mistakes were abundant, from CNN’s on-air claim of confirmation that babies had been beheaded, followed by a retraction, to The New York Times running with later debunked reports that an Israeli strike had killed hundreds at al-Ahli hospital.

The fog of war had become more of a hurricane of misinformation. It became hard to avoid questions from students on how additive the foreign correspondent is. “That old model of sending out someone from the head office and they would send dispatches back is dying,” Richburg says. “Why would we need it when there are so many Palestinians who can do it?”

Palestinian journalists have done all the reporting from Gaza as foreign reporters are shut out and banned from entering the Gaza Strip. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, over 70 Palestinian journalists have been killed by Israeli fire in the first few months of the war alone. Many have lost family members, been displaced many times, and are working and living amid a massive humanitarian crisis. As local journalists film the war and its impact, the foreign correspondent — who in the past would work alongside them, acting as the face of much of the TV reporting — has in part fallen away, relegated to the other side of the perimeter fence, adding to the growing conversation about our relevance and role in modern war coverage.

Over the years, reporters from Afghanistan, Syria and beyond have grown in numbers and skills, as have indigenous news outlets, but issues of objectivity only increase when those on the ground from specific conflict areas, often activists rather than traditional journalists, are those doing on-the-ground reporting. “Journalism is a trade, it’s a series of things you learn how to do by doing them,” says Paul Wood, a former senior correspondent at the BBC. “But above all, it’s the objectivism. If you have an ax to grind you may as well be a party to the conflict. We all have our biases, but we try to leave them at home. You still have a moral compass, rape is rape and murder is murder. But you cannot take one side.”

The skills Wood refers to involve storytelling that can captivate readers and viewers back home. To build a narrative arc around characters and events that fairly encapsulate what’s at the heart of a conflict often takes many years of experience, and building such narratives in a way that doesn’t take a moral stance is a skill best honed from years of reporting from a variety of conflicts. To have covered not just one war, but numerous wars, is the greatest training to understand the gray areas and complexities lost in biased reporting. It’s also about a sense of objectivity. Traditional, more old-fashioned foreign correspondents approached stories not to change events but to help the reader or viewer better understand what was happening.

In modern-day journalism, activism and opinion has seeped deeper into the words and stories told. Both foreign correspondents and locals are increasingly leaning into identities and personal politics. The old argument that foreign correspondents, as professionals without skin in the game, would be more objective, was always only a half-truth, argues Richburg.

“That was always a conceit — that the guy sent out from headquarters was always going to be more subjective,” he says. “We already bring our own share of biases that we don’t like to acknowledge.” Both the growth in local journalism and the current cultural squeamishness at Western, often white, reporters flying to war zones has drawn criticism of the traditional image of the war correspondent. Given that many countries experiencing conflict do indeed have journalists there, vocal criticism of “parachute journalism” has grown in recent years. Yet, the ranks of the war reporter among American outlets are increasingly diverse, and many fly in from their homes located in the region. Reporters who have familial ties to the region can bring with them language skills and a cultural understanding that helps them gain better access, as well as add a nuanced humanity to their work. After showing my students the breathless live news reporting of the “shock and awe” bombardment of Baghdad in March 2003, and embedded reporting of journalists with the U.S. Army as it invaded Iraq, they read Anthony Shadid’s remarkable reports from inside the homes of Iraqis. The two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning Lebanese American correspondent reported with unmatched tenderness and detail on the experiences and evolving opinions of Iraqis from all over the country. His warm personality, fluent Arabic and Islamic affairs expertise helped him gain people’s trust and spend time inside their communities.

Living in the region is important. When foreign correspondents have moved to Beirut or Cairo, Sanaa or Damascus, or elsewhere in other regions of the world, they are forced to spend huge amounts of time within communities, many times learning the language. Their interactions are not limited to academics, politicians and military commanders. Quaint as it sounds, daily interactions with service workers, neighbors, local officials and business owners shape understanding of the variety of complex perspectives on the ground. It’s also a literal reminder that life exists — and society functions — beyond the confines of war. Those of us living in the field used to joke about how journalists flying in from Western countries would interview their taxi driver from the airport. If you pay attention, you might notice a lot of cabbies quoted in Western newspaper reports.

The fog of war has become more of a hurricane of misinformation.

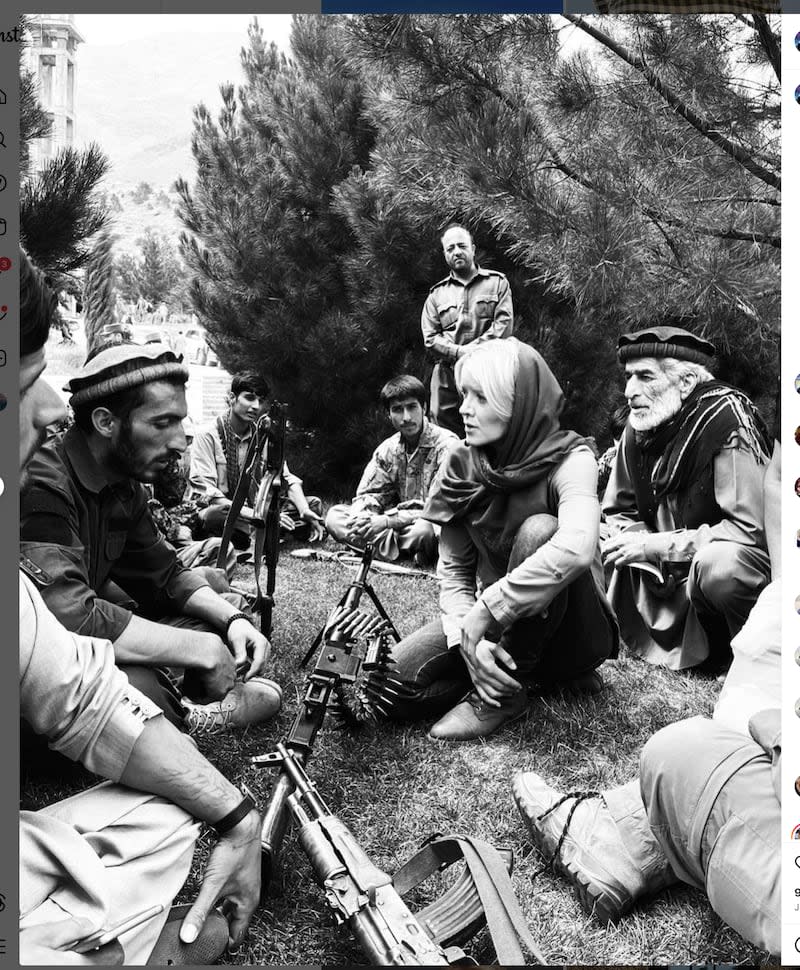

I lived in the Middle East for 14 years as a war reporter — my parachute was usually a very short Middle East Airlines flight followed by a bumpy drive. If there is a case to be made for the traditional war reporter, it’s cultural, or rather an ability to humanize stories in a universal way that connects back home. When I reported on the Taliban’s crackdown on Afghan women’s rights for “PBS NewsHour,” I wanted my audience to connect with and understand what the loss of their rights meant to women as individuals. I profiled a female gynecologist who worked her entire life to build a practice, rising to become one of the nation’s leading doctors. With the Taliban now in charge, she was faced with having to leave the country — and with it her right to practice medicine and her daughters’ access to education. She told her story with intensity and emotional honesty when I sat to interview her. This piece was not simply about the denial of women’s and girls’ rights, but the sacrifices mothers make for their children — something I knew many in the Western audience would relate to. Knowing the readership can be just as important as knowing the cultures from which you are reporting; a hard-won lesson learned by many foreign correspondents.

But those are the rules of news specials and features. When it comes to breaking news, it’s simply not possible or necessary for foreign correspondents to be on the spot when news happens. Today almost the entire world is carrying a camera in their pocket. With social media, anyone is capable of sending information out like a news agency. The result? Reporting is technically open to anyone in the right place at the right time, and not limited to those working for news outlets. When Beirut was devastated by a massive explosion at the city’s port in August 2020, I had by pure luck just moved to New York City a few weeks before. As I unpacked boxes in my new apartment, I began seeing images and videos of the destruction of my former home. It took over an hour of scrolling through raw images on Twitter for news reports to even begin to clarify what had happened. It was a vivid example, and in this case a personal one, of the new norm of content appearing before verified news.

Beirut’s port explosion was an example of how powerful this ability to be connected to people in real time is. The world can be aware almost instantly of what is happening, which has proved to be a vital lifeline for those living under insufferable repression from regimes that effectively ban both international and domestic reporters.

In Myanmar following the military coup of 2021, the crackdown on pro-democracy activists was swift, brutal and conducted in the shadows. Fighting between ethnic armed groups and the junta has displaced over 2 million, according to the United Nations. Whatever trickle of images and information making it out is coming from local “citizen journalists.” This phenomenon began in earnest a decade before.

Blocking journalists from war zones, denying visas and discouraging the very presence of journalists by killing them used to be something more akin to dictatorships. It has become much more common these days.

The Syrian Civil War changed war reporting. It was a war where the rebels, hopelessly outgunned, welcomed and helped journalists visit the areas they held. Reporters like Paul Wood and myself were whisked from Beirut’s bustling streets and smuggled across the border to Lebanon to show the extent of the Bashar al-Assad regime’s crackdown on protests and the growing armed uprising. It was incredibly dangerous work, as exemplified in the killing of American journalist Marie Colvin on Feb. 22, 2012, but provided extraordinary access.

Driving through the night from Beirut to avoid detection from Hezbollah-allied soldiers, I was ferried through the backroads of Lebanon and foggy fields to the border. For several days I was passed from one safe house to another, hosted by a network of sympathetic civilians, until I was in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs city, the origin of the uprising. The activists, young men who had been involved in opposition protests for months, took massive risks to get me and my colleagues into Syria because they wanted the rest of the world to know what was happening. Over the noise of tank shells and the crack of sniper rounds, one of them laughed, “Welcome to Syria!” I shuddered.

In the control center of their rebellion, they sat around on the floor, frantically smoking, uploading videos and content they had shot to YouTube and Facebook. While the trickle of journalists making it into Baba Amr could only bring out a certain amount of footage and reporting, the activists took the lead in filling in the blanks. They were doing the job of news organizations for themselves, and many American and European outlets aired their footage from field hospitals and basements filled with sheltering civilians.

This footage was vital to helping the world understand what was happening after Bashar al-Assad claimed he was killing “terrorists.” But the footage was more activism than reporting, in large part because it was done with an outcome in mind. These young men wanted the West’s help. They had seen what intervention in Libya just months before had done to cripple the Qaddafi regime, and hoped for similar aid. Sitting on the floor of the apartment they had based themselves in, they smoked and watched TV coverage of the emergency U.N. Security Council meetings, their laptops open, waiting for footage to upload slowly on a weak internet connection. “Do you think Obama will do a No Fly Zone?” one of them asked me. Most of the young men in that room would later disappear into Syria’s jails or battlegrounds and never be seen again.

Their work gave the world access to a war that a dictatorship did not wish to be seen. It also highlighted the limitations of such reporting. At times, the activists, both untrained in professional reporting and motivated by their desire to overthrow the Syrian government, partly staged scenes in some of their videos. At one point, they were caught setting fire to tires to provide a cloud of smoke behind them while addressing the camera.

Gaza is now the clearest example of a people filming their war for themselves and sending it out for the world to see. Technological advances, coupled with social media accounts, are providing an enormous platform for growing citizen journalism, as well as activism, as access has become one of the greatest challenges to the traditional war reporter. Blocking journalists from war zones, denying visas, preventing any embeds with militaries and discouraging the very presence of journalists by killing them used to be something more akin to dictatorships. It has become much more common these days, losing its taboo among democratic states. As the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan dragged into its final years, military commanders took advantage of the growing apathy in the U.S. toward the war to effectively ban reporters.

If journalists aren’t able to gain access and report in conflict zones, we have no opportunity to utilize the strengths of foreign correspondence. Instead, our information will be limited, coming only from local activists and reporters. The more restrictions that are in place for those trying to bring information home, the more the fog of war will continue to crystallize into an impenetrable wall.

In 2019, after recording an interview with a senior Afghan defense official, I took the opportunity as we sipped tea to press him for access to Afghan troops on the battlefield. Afghan government soldiers and police were being killed in record numbers and I knew the Kabul government wanted the U.S. to acknowledge the sacrifices being made. I explained that commanders were denying our requests. “We would love to do embeds with American reporters,” said the official, before pausing and lowering his voice. “But we cannot.”

“The Americans have told you not to?” I asked.

“Yes, they have been very clear — no journalists,” he said, looking down at his hands.

Two years later, I and foreign correspondents from some of the biggest American media outlets all signed a letter of petition to the Pentagon, urging more transparency and access to the war in Afghanistan. There was no response. By the end of the war, the running joke was that it was easier to access embeds with the Taliban than it was with U.S. or Afghan government troops. It was — I spent more time with Taliban units than any other.

Jane Ferguson is a foreign correspondent for “PBS NewsHour” and the author of “No Ordinary Assignment, A Memoir.”

This story appears in the March 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.