So, What’s Going on With Clarence Thomas These Days?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Next week marks the last week of oral arguments in this Supreme Court term, leaving little more than a sprint through the remaining decisions left unsettled. As of this writing, some heady matters remain unresolved. The ruling on the abortion pill has yet to be decided; there is a consequential gun rights case on the docket; and as always, the fate of the administrative state hangs in the balance. For many ordinary people, it will be another white-knuckle stretch, as they hope for narrow rulings that might limit the potentially life-altering—and precedent-shattering—damage.

For Democrats, the 6–3 split on the high court is a generational problem. At least, that’s how it’s often framed. In a recent post, my colleague Matt Ford stated the matter pretty starkly: “By some estimates, liberals may not have a chance to appoint a majority of Supreme Court justices until the 2050s. If Barrett stays on the court until she is the same age as Ginsburg, she will serve until at least 2059.” To think about this dilemma in these terms is to resign oneself to the idea that the solution won’t be arriving for several decades. But a lot can happen between now and 2059, and perhaps even sooner, because of another immutable law that holds that “shit happens.”

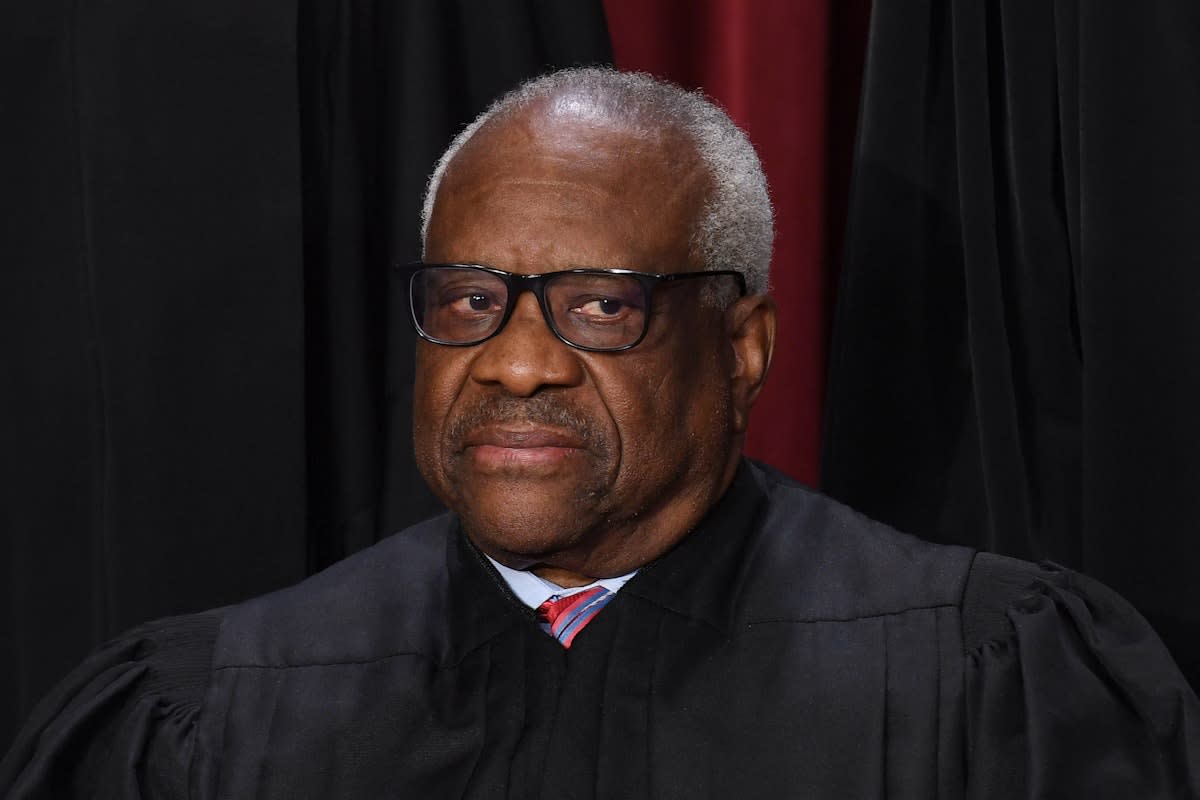

With that in mind, has anyone noticed that something seems to be up with Justice Clarence Thomas lately?

This past Monday, it was reported that Thomas was absent from the court and not participating remotely in the oral arguments of the day, with Chief Justice John Roberts assuring everyone that Thomas would get the full range of “briefs and transcripts” after the fact, ensuring that he’d be able to participate in the cases. Thomas doesn’t miss many days of work, and unlike a previous instance two years ago in which he missed a number of sessions during a hospital stay, no reason for his most recent absence was offered.

Into this blank space in the story, allow me to remind everyone that Thomas, 75, is the oldest of the justices, the longest-serving member of the court, and while I don’t doubt that Harlan Crow’s Garden of Dictators may be the venue for eldritch incantations of all varieties, there is no reason to believe that Thomas is immortal. In other words, he is still subject to the vagaries of the Universal Law of Shit Happening. (Fun fact: Samuel Alito is only a year younger than Thomas.)

It’s really no one’s fault that the comings and goings of sitting Supreme Court justices can be such a macabre business. Given the opportunity to amend the Founders’ work, I imagine that ending the whole “lifetime appointments for wizened, unaccountable elders in robes with the final say over American life” arrangement would be near the top of the list of improvements. But Democrats are probably too physiologically incapable of stating the potential stakes of the upcoming election to their voters in terms as stark as “Clarence Thomas might not be long for the bench; send Biden back to stem the tide of far-right jurisprudence.”

It’s not as if taking the high road hasn’t led anywhere: As The New Republic contributor Simon Lazarus has pointed out several times, a combination of consistent pressure and high-minded critique from liberals has, over the course of the past few terms, seemed to play a role in the justices taking a more tempered approach to their rulings. This strategy may yet bear more fruit this term, and forestall the kinds of extreme rulings that the conservative bloc’s two elder statesmen might hope to wrangle.

Still it’s weird to watch how some on the left are raising the salience of the justices’ mortality: by urging Democrats to bring Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s career to a premature end, the better to install a younger jurist now while Biden is still president. In that aforementioned article, Ford took a dim view of this way of thinking and suggested instead that Democrats might be better off simply winning elections. Regardless, this is a debate worth moving on from. It’s silly for Democrats to be divided in an election year over anything, let alone Sotomayor’s career, and anyway, no one’s run this plan to pull a late-in-the-day switcheroo past Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, whose permission is still required for such stunts.

Nevertheless, there is definitely a ruthlessness gap between the parties in this regard. Republicans have had enormous success in dispensing with the polite traditions that govern the high court’s promotions and relegations. That the GOP went to elaborate lengths to prevent Obama from appointing Merrick Garland to the bench was, during that ongoing folderol, evidence of how far they were willing to go to consolidate power. But it is also a reminder that there was once a time when the makeup of the Supreme Court wasn’t in their favor and they were staring down the tunnel of the same kind of generational problem that Democrats now face.

But the right has benefited from the happenstances of the Shit Happens Law, as well. The misfortuned timing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death created the opportunity for the 6–3 split and provided the catalyst for the Democrats’ recent agita over Sotomayor. Still, the lessons of the recent past—combined with all this recent talk of court-vacancy gamesmanship—illuminates a simple idea that Democrats should perhaps find the courage to speak aloud, regardless of the grisly implications: Elections matter, because you never know when the chance to appoint a new justice might arise. There is a clear mission at hand: Don’t let any of the court’s elder conservatives have the opportunity to make their escape through the safe harbor of a Trump presidency.