Frenchtown fights to survive, preserve history as it's squeezed by student housing

In Frenchtown, no matter the street, no matter the corner, every day is a reminder of what's happened and what's coming.

Tallahassee celebrates its 200-year anniversary this year. Yet, the face of Frenchtown, which has long been the state's oldest primarily Black neighborhood, is fading and changing a block from the governor's mansion ‒ and with barely a mention amid the pomp of the bicentennial milestone.

Former longtime businesses on 11 parcels at and near West Tennessee and Macomb streets were razed to make room for a seven-story, 500,000 square-foot apartment building aimed at college students, particularly Florida State students since it will rise near the fringes of campus.

It's one of several student housing properties standing tall in the neighborhood — all signs of a shrinking Frenchtown as locals remember the past and get a glimpse into the future, one that's both welcomed and worrisome.

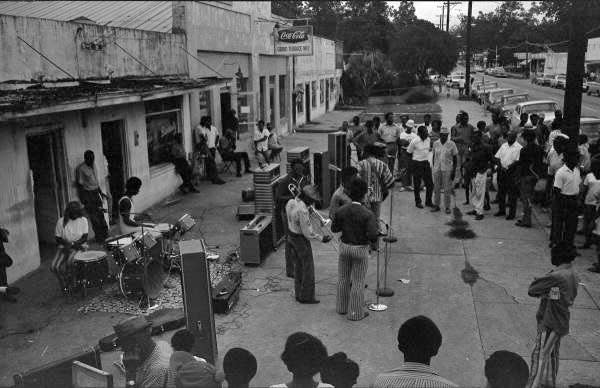

Residents hear the clamor of construction on the horizon as excavators claw into the red-clay earth. Other sounds used to be here.

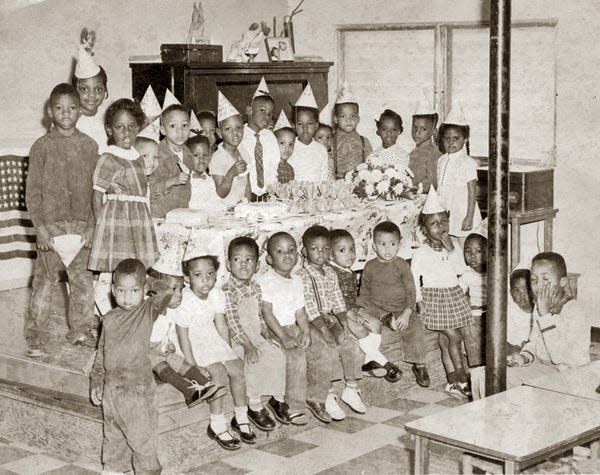

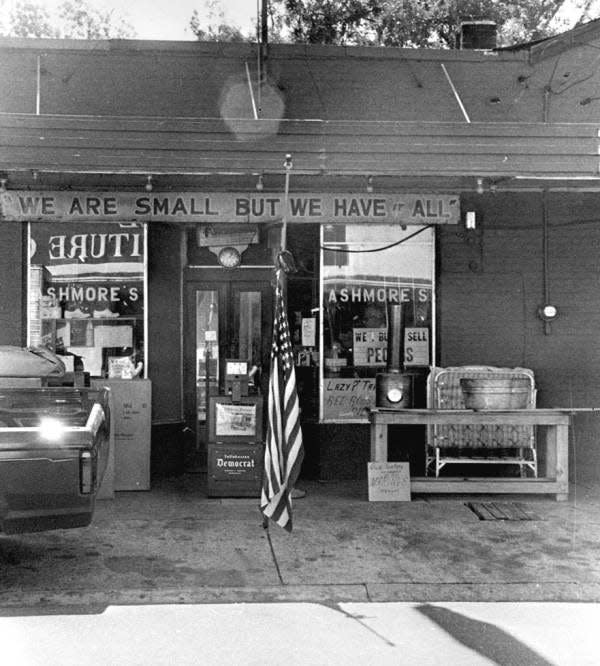

Chatter spilling out from night clubs like Red Bird Cafe and Nell's Pool Room, giddy Black boys and girls running to Ashmore's Drug Store for an ice cold Coca Cola and must-see performances from famous Black artists like Cab Calloway, Al Green and others who made Frenchtown a pitstop on the way to New Orleans and other cities.

The neighborhood, as many saw it, had life. From grocery stores, a dry cleaners and a pharmacy, it had its own economic engine with an estimated 100 thriving businesses over the years. Families didn't have to venture far from the nest; everything they needed was within reach in Frenchtown's prime.

But Frenchtown lost much of its luster when street drugs, crime and homelessness ravaged the neighborhood in the 1980s and it's never fully rebounded. Even with efforts to improve livability, it's still plagued by poverty.

It now faces a new frontier as more student housing projects and developments sprout up amid the neighborhood's mix of rehabilitated and rundown homes. Only a handful of longtime, Black-owned businesses have survived, many of which see and hear the signs and sounds of change just outside their windows. Every day.

'Constantly reminded that change is going to come'

The Frenchtown neighborhood sits northwest of downtown Tallahassee with FSU and the Griffin Heights and Levy Park neighborhoods as their immediate neighbors.

At least once a month, Alexis McMillan is contacted by someone inquiring if she'd sell her business.

She sat in one of two chairs near the entrance of Economy Drug Store, the same pharmacy her dad owned 75 years ago. It's a retro throwback where the interior has remained frozen in time. Shelves are stocked with essentials, paper towels, toiletries, greeting cards and more.

"I had some of the chain stores to send information to us or call us saying 'we're representing this big box company and want to know if you're interested or this, that and the other,' " said the second-generation pharmacist, who's determined to hold out.

"We want to be in business for as long as we can be in business," McMillan said.

She peered out the window facing Macomb Street, remembering pecan trees dotting the landscape where construction cranes now hang in the open air. It wasn't long before more memories stirred, and she mentioned names of people and businesses that have come and gone.

For her, old Frenchtown doesn't seem so long ago. She often wonders if the historically Black neighborhood can coexist with growing development.

"I'm constantly reminded that change is going to come and you have to roll with the punches," said McMillan, adding it affects her business. "I'm also reminded that just means I need to upgrade to whatever the student population wants from there and diagonally across and a few blocks down."

Some business owners suspect Frenchtown as they know it will buckle under the pressure of powerful developers hunting for real estate in urban areas.

"In 10 years, it will be gone," said Roderick Sheffield, prophesying the future of Frenchtown. "You can't keep squeezing a balloon before it pops."

He comes from a long line of Sheffields that have left fingerprints for generations in Frenchtown. He owns Sheffield Body Shop on Fourth Avenue with his nephew, Carlton Sheffield Jr., a business that's been open for more than 60 years.

His family once owned a nightclub on Old Bainbridge Road that's now home to the Tallahassee Urban League. Another business, Modern Cleaners, was in the family, along with the former Tropicana Pool Hall where the Renaissance Center now sits.

Roderick Sheffield said he also owns residential and commercial property in Frenchtown, and he's disappointed to see the neighborhood's decline.

"I personally feel our Black officials and leaders let Frenchtown down, because they let crime and this gun violence get out of control," he said. "It has been this way for over 40 years."

Snapshot of Frenchtown's origin story

As Tallahassee celebrates its bicentennial anniversary this year, the early days shaped the city and Frenchtown.

In 1824, new settlers erected temporary tents and "a frontier was born," wrote author Julianne Hare in her book, "Historic Frenchtown: Heart and Heritage in Tallahassee."

The infancy of the city's land grid began, followed by provisions for government buildings, a cemetery, churches and several city parks, wrote Hare, adding "Soon, the Third Florida Legislative Council had a third place to meet and, it was indeed, roughly halfway between Pensacola and St. Augustine."

Within a year, there were 120 structures and roughly 800 residents in early Tallahassee, which is an American version of an Indian name "Tallahassa" that means abandoned or old fields.

The first families were "men of means" and described as an eclectic group, in Hare's book. They were doctors, lawyers and military survivors of the Revolution, the War of 1812 and First Seminole War, along with many Europeans who came from "Germany, Holland, Ireland, Scotland, Great Britain and other countries to escape privation, persecution, or simply start a new life."

"Outnumbering them all were the slaves of the African descent who came unwillingly and persons of color who could trace their roots back to the Indian Americas and escaped slaves who lived in relative freedom under Spanish rule," Hare wrote.

As a token of its gratitude for aid during the American Revolution, the United States Government gave "$200,000 and his choice of a full township (36 square miles)" to Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette."

The area was dubbed "Frenchtown" for the early settlers of French descent who called the land home – although, Hare also details other theories and legends on how the area became known as Frenchtown.

"Whatever the origin of the name, we know that Frenchtown has always been home to small business owners, tradesmen, and blue-collar workers," Hare wrote. "We also know that it has been predominantly occupied by people of color since the time of the Civil War."

Yet, today, Frenchtown's distinction as the oldest primarily Black neighborhood in Florida may be slipping away.

Efforts to improve Frenchtown

Many residents believe Frenchtown's economic foundation began to crack following integration in the early 1960s. Black men and women were no longer bound by discriminatory Jim Crow laws and "whites only" signs at businesses and public spaces.

Financial support seeped out of Frenchtown. It wasn't long, just a matter of years, and Frenchtown began to lose its economic footing as the Black business mecca for Tallahassee.

It was still a destination for people like Curtis Taylor, a then young "country boy who grew up on a farm" and came to Tallahassee as a freshman football player at Florida A&M University.

One day, after a grueling practice, him and some friends asked where they "could go for some action in Tallahassee and everybody in unison said Frenchtown."

With no car among them, they trekked more than two miles from FAMU's campus to Frenchtown.

"I'll never forget, when we got to St. Mary (St Mary Primitive Baptist) on Call Street, we were at the top of the hill and you could look down at Frenchtown ... it was so many people you could not see the ground."

Now, outside his office window, he sees a different neighborhood.

Taylor, president and CEO of the Tallahassee Urban League, wants to see the city put more effort behind low-cost, high-impact priorities, such as cutting back trees and vegetation that's being used to conceal drug activity in the neighborhood.

"I see it every day," said Taylor, looking out the window and pointing to unkept bushes across the street. "People go in there, and they'll put stuff up there and come back out and sit and so when the police come drive by they won't see anything. They'll go back there, drop something off there, come back and get it all day long."

The Urban League is one of many organizations playing a role in helping to restore Frenchtown and surrounding neighborhoods. Some of its main efforts include rehabbing single-family homes for existing homeowners and potential new residents.

More attention and resources have trickled into Frenchtown. The city of Tallahassee has an entire page on its website dedicated to the neighborhood, challenges, concerns from residents and plans to improve the neighborhood.

For example, as it relates to housing, the neighborhood’s median income is over $24,000 per year, according to the city.

"Some residents are not in a financial position to prioritize home repairs or improvements," the city's Frenchtown Neighborhood First Plan said.

"Longtime residents have seen the quality of the neighborhood’s housing stock decline as structures have aged," it said. "As of 2018, 30% of the structures in the neighborhood were built in 1910-1950; 41% were built in 1951-2000; and 9% were built in 2001-2016 (data was not available for 20% of the parcels, indicative of parcels with no structures). Some Frenchtown residents have limited resources to repair and maintain their homes and the resources available to make the needed repairs are also very limited."

The 2019 debut of Casañas Village on Macomb and Georgia streets was an attempt to bring affordable housing to Frenchtown. With a $20.4 million price tag, the 88-unit unit apartment building is a mix of affordable and market-rate apartments.

In addition to the city, the Tallahassee Community Redevelopment Agency is another resource for certain improvements and redevelopments.

Many residents, including Taylor, said much of Frenchtown's problems can be addressed by targeting crime and housing, particularly housing that doesn't push existing residents out of their homes and attracts new residents that aren't just college students.

"Frenchtown can be saved," Taylor said. "Frenchtown can be transformed. Frenchtown can be turned around, but it's going to take a unified effort. We're going to need all hands on deck."

Frenchtown residents: 'Change makes you have to change'

Many have tried to fight for improvements. For some, the fight continues and for others, they don't see the point.

Frenchtown, as O'Neil "Boss Man" Jackson Jr. knows it, vanished a long time ago.

Inside his North Macomb Street home, the same one where the 79-year-old was born along with countless others in his family tree, Jackson reminisces. His voice, heavy and husky, amplifies his griot and patriarch status as a familiar and respected face in the neighborhood.

He gently sways back and forth in a bone-colored rocking chair in his tight living room, surrounded by a museum of family portraits on nearly every inch of his walls. Many of them are gone, much like the institutions he remembers as a child growing up in Frenchtown.

From jewelry and grocery stores and restaurants, Jackson said, "Black folks had businesses."

"You got two issues ... you're going to have change. But, by that same token, ain't nothing I can do about it," said Jackson, a retired longtime educator who's lived in Frenchtown much of his life.

Sitting in his home, located in the Goodbread Hills community, Jackson said city and county leaders allowed Frenchtown to be picked apart for the taking.

"You got rid of a Black Wall Street with an intent for the purpose of Florida State University and to get the Black folks out of the heart of the city," Jackson said. "You killed two birds with one stone."

Frenchtown's status as a primarily Black neighborhood may indeed be fading.

A 2019 Frenchtown Neighborhood First Plan, designed to be a resident-led guide toward improving the community, stated Frenchtown's total population was 5,716, including 2,053 households.

The 135-page report said this represented a growth of 25.33% from the 2000 total population of 4,130; a median age is 29 and 33% of the population ranged from ages of 15-24. Frenchtown's racial makeup was 51.3% Black, 42.8 % white, 1.9% Asian and 2.3% who identify as two or more races.

City planners said the latest estimates won't be known until June. It's likely the neighborhood's demographics have shifted considering, for example, The Standard opened in 2019 as a new apartment building with 876 beds.

"Ain't nothing nobody can do about it because money is the name of the game," Jackson said.

As Jackson talks, he hears a familiar voice outside his screen door. A pleasant face comes into view: Karen Robinson, one of his tenants who lives in Frenchtown.

She popped in for a brief chat with Jackson and soon shared her take on the neighborhood after living in Frenchtown for seven years.

Robinson, 48, sees the change from her home in the neighborhood but said "Goodbread pretty much has stayed Goodbread, for the most part."

"There are new people moving in and out consistently. Whether it'd be a relative, whether it'd be someone from the outside that's not a relative," said Robinson, who has a nursing background and works various jobs. "It's definitely changing as far as Frenchtown and Goodbread is concerned."

Yet, the Chicago native sees another side of the changing face of Frenchtown.

"I think change is always good considering the fact that Tallahassee is so small but big," she continued. "It's very hard to explain, coming from a big city ... That change can be great if it's welcomed.

"Change makes you have to change, so change is not always welcomed," she said. "But, once it's there and it's happening, you can't do anything but blend right into it."

Optimism for Frenchtown's future: 'It's progress'

In talking to business owners, advocates and church leaders, it's clear that many believe Frenchtown still has potential to bring value to its residents and rebuild its legacy as an established neighborhood with deep roots in the Black community.

Many don't want to see it become just a name people say, much like what happened to Smokey Hollow.

Smokey Hollow was a thriving Black community in what is now downtown Tallahassee. It had churches, restaurants, retail stores and businesses, much like Frenchtown. In 1920, Smokey Hollow had 270 residents, representing 1 out of 10 Black residents in Tallahassee.

Post Civil War to the 1960s, the neighborhood was a beacon of Black-owned homes and vitality for the working class less than a mile away from the Capitol.

However, many residents were forced to leave due to the construction of Apalachee Parkway in the 1950s. The remaining residents were pushed out a decade later when the state built the Florida Department of Transportation building.

All that remains now is a memorial at Cascades Park of the "spirit houses," representations of homes commonly seen in Smokey Hollow.

While Frenchtown may be changing, its spirit and possibility endure for people like the Rev. RB Holmes Jr., longtime pastor at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church.

Located on the corner of West Tennessee Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, the church sits across the street from Frenchtown's edge and has been an investment champion for the neighborhood by shepherding numerous projects. Holmes, however, said some level of change is inevitable.

"Frenchtown would probably never be what it was 50 years ago or 60 years ago," he said. "That just comes with life."

Bethel's record of bringing economic development to Frenchtown includes a mix of successful projects and others that didn't pan out.

Several years ago, plans surfaced to redevelop a highly visible block in Frenchtown — directly from what will soon be Hub Tallahassee student housing. A group of land owners called themselves the Frenchtown Redevelopment Partners, which consisted of Bethel Missionary Baptist Church and others with parcels along the 400 block of West Tennessee Street that include the former homeless shelter site.

At the time, the $78-million, mixed-use redevelopment included approximately 250 condos and apartments and more than 58,000 square feet of retail space, office space and parking. The vision didn't come to fruition, with Holmes saying, "you can't make people do what they don't want to do with their land."

Holmes believes there are positives as Frenchtown evolves and said churches, such as Bethel, are the anchor for "real community revitalization."

In the early 90s, the church opened its 63-unit Bethel Towers, an affordable housing facility for senior citizens.

In 2005, at the time, Bethel was the first to bring new single family homes into Frenchtown with the construction of Carolina Oaks, a 25-home subdivision aimed at first-time homebuyers that's wrapped by North Macomb, West Carolina and West Georgia streets and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

Most recently, Bethel sold a roughly half-acre lot to Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare so the hospital could build and operate a new 4,000 square-foot urgent care facility — the neighborhood's first stand-alone healthcare facility.

Despite the fact that almost all of Bethel's membership lives outside of Frenchtown, Holmes said the church has redirected and invested millions of dollars toward improving its living conditions.

Holmes, looking to the future, sees homeownership as a continued mission that started with Carolina Oaks and now other housing projects underway along the fringes of Frenchtown on Tharpe Street and other parts of the city, such as Ridge Road.

He stressed homeownership will change who has a stakeholder voice in Frenchtown's future, adding "once you lose home ownership, you lose a great degree of history."

He also said local government is poised to act. For the first time during his tenure as Bethel's longtime pastor, Holmes said the "right political climate" is in place toward addressing issues in "marginalized communities" like Frenchtown.

"The challenge has been working together," Holmes said. "The common good should be preserving the history of the community by creating homes, apartments, dealing with the food and health disparities.

"How do we do that?" he asked. "It took a long time, but I think there are some groups that are doing that."

That same optimism is shared by some business owners.

On a segment of Macomb Street about a half mile away, Herbert Dickey is a Frenchtown businessman with a full view of the latest student housing project outside his window.

He owns and operates Dickey's Barbershop on Macomb Street and said the neighborhood needs the change unfolding, adding "it's progress."

"Places like Atlanta, Orlando are changing, and we need that same look," said Dickey, inside his barbershop. "We don't need rundown houses, abandoned buildings, people standing around doing only God knows what."

Dickey, born and raised in Frenchtown, said he's seen his fair share of residents moving or passing away, leaving a population void.

The neighborhood, he said, needs to look like someone cares about it.

"We need work. It needs to look like progress. It needs to look important," he added. "We are important."

Contact Economic Development Reporter TaMaryn Waters at tlwaters@tallahassee.com and follow @TaMarynWaters on X.

This article originally appeared on Tallahassee Democrat: Frenchtown in Tallahassee fights to survive amid student housing boom