The forgotten ‘comfort women’ of the Philippines – and their struggle for justice

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Maria Quilantang was one of the lucky ones. To this day, she can still remember the sound of warplanes and the footsteps of Japanese soldiers as they stormed her village in central Philippines.

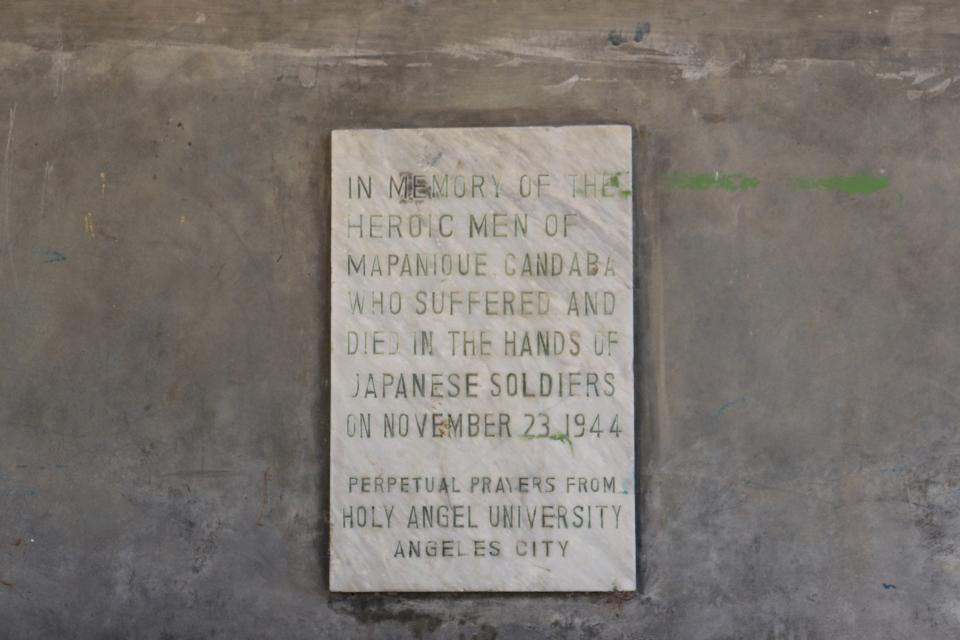

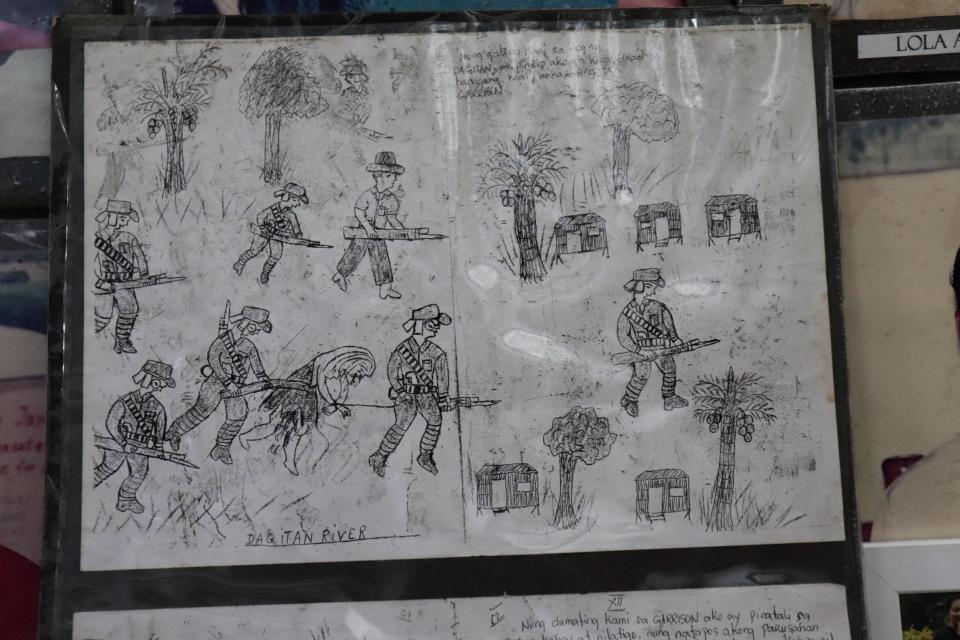

During the surprise attack, which took place at Mapaniqui in November 1944, houses were torched and many of the local men shot on suspicion of being resistance fighters. Some of the villagers were violently beaten in front of their own children.

“Our parents were punished,” said Quilantang, 88. “Some were tied, and the others were being kicked. We could only watch. My parents lost consciousness for a long time.”

Although Quilantang was able to escape – she ran into the dense undergrowth of the surrounding forest and eventually took refuge in a neighbouring village – her mother and sisters were taken to the so-called ‘Red House,’ a nearby mansion that served as a headquarters for the Imperial Japanese army.

There, the women and girls, some as young as eight at the time, were detained for weeks, beaten and raped by soldiers.

They were among 1,000 Filipino women forced into sexual enslavement during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Many women died or committed suicide due to brutal mistreatment and sustained physical and emotional distress.

In total, 200,000 ‘comfort women’ are estimated to have endured similar experiences across Asia during World War Two, as the Japanese army occupied one country after another, from Korea to Indonesia, subjecting their people to oppression, executions, and sexual violence.

Today, Japan faces ongoing diplomatic pressure from several countries in the region to apologise for its actions during the war and pay reparations.

Although millions have been paid in compensation to Korea – home to the majority of the war’s comfort women – for the Philippines, there has been little acknowledgment of what happened in villages like Mapaniqui.

Filipino campaigners are doing what they can to change this, but it’s proving a tough fight.

Since its inception in 1997, a comfort women survivors group called Malaya Lolas, led by Quilantang, has repeatedly called on the Filipino government to press their case with Japan.

There have been protests in Manila, court cases and government lobbying – though such action has largely been ineffective.

In 2019, opting to circumvent the Filipino government, Malaya Lolas filed a complaint to the United Nations in which they detailed their abuse at the hands of Japanese soldiers.

The complainant called for reparations and the recognition of their sufferings at the hands of Japanese soldiers. At the same time, it also urges the UN to step in and compel the Filipino government to support the nation’s surviving comfort women.

In the Philippines, only 40 victims of Japan’s sexual enslavement are still alive today. One of them is 94-year-old Maxima Mangulabnan, another villager from Mapaniqui who, in the wake of the 1944 attack, was raped by Japanese soldiers and later taken to the Red House.

Mangulabnan no longer lives in Mapaniqui, having moved to another province, but she has passed some of the stories of the war onto her daughter Estelita.

“The people of Mapaniqui were running. The bombs were coming and they were dying. They were hiding in different places but they couldn’t go far,” said Estelita. “Both my mother and grandmother were raped.”

For so long, such experiences remained hidden within families, a secret shame, only shared from one generation to the next.

But in the early 1990s, the women of Mapaniqui travelled to Manila, the capital of the Philippines, to lobby for government support for their plight.

“It fell on deaf ears,” Quilantang said.

It was the beginning of a long struggle for justice.

The road to reparations

In 1995, the divisive Asian Women’s Fund, a reparations scheme for comfort women created by the Japanese government, began compensating victims.

However, the women of Mapaniqu and other members of Malaya Lolas were denied access to the fund as they were not considered to have been abused for a long enough period.

In 2004, the group reached out to the Philippine Supreme Court to compel the state to aid them in their pursuit of restitution but the petition was dismissed in 2010. The court ruled that only the president can decide to represent the “comfort women” in their demands to Japan.

A subsequent move to appeal the decision was also rejected four years later.

“The Supreme Court said it sympathises with the experiences of Malaya Lolas but it also said that it’s a political question, a political question that only the executive department or only the president of the Philippines can decide and he can’t be forced by the court,” said Virginia Suarez, a lawyer for Malaya Lolas.

After exhausting all possible legal remedies on the domestic front, the women carried their fight for justice to the UN, arguing that the Filipino government has failed to address sexual violence against the survivors by refusing to represent their demands for reparations.

There have been some successes, though.

In March 2023, Malaya Lolas scored a landmark victory after the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) found that the state had violated the rights of the victims by failing to offer proper recognition and redress for their suffering.

The decision also directed the state to dispense “full reparation, including recognition and redress, an official apology and material and moral damages”.

Following the ruling, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr ordered government agencies to craft a “comprehensive response” to the ruling. Department of Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla promised to discuss with lawmakers a potential law that would help the victims.

A key suggestion made by CEDAW was the creation of a “state-sanctioned fund to provide compensation and other forms of reparation to women who are victims of war crimes.” Yet there have been no signs yet from the government or Congress about creating such a fund.

As a result of campaigners’ refusal to quit, the issue of the Philippine’s comfort women has shadowed over the Marcos Jr administration for many years.

During the president’s trip to Japan in February 2023, the Department of Foreign Affairs told reporters that Marcos Jr would not explore the subject with his counterpart, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

“We don’t expect it to be raised. But the position of the Philippines on this issue is that compensation claims by former comfort women are considered to be already settled as far as the government is concerned,” a department spokesperson said.

This response highlights the state’s reluctance to upset Japan, the largest lender of foreign aid in the Philippines. From 2001 to 2020, development assistance from Japan reached $19.65 billion, according to the Department of Finance.

“The position of the Philippine government is difficult. It doesn’t have any bargaining leverage with the Japanese government,” said Sharon Cabusao-Silva of Lila Pilipina, another organisation for comfort women.

“The Japanese government remains the number one creditor country to the Philippines, funding many of its flagship projects under the current and past Philippine governments. That puts us in a very weak position.”

Besides loans for development programs, the Marcos Jr administration also seeks to expand military ties with Japan. A defence agreement allowing troops to operate within the territories of both nations is on the table, with a deal expected to be signed soon.

Such arrangements have been heavily criticised by campaigners like Cabusao-Silva.

“Japan has not even apologised yet for its atrocities during World War Two and to the Philippine comfort women. Even the Filipino individuals harmed severely by the actions of the Japanese Imperial Army have not received an acceptable standard for justice,” she said.

As Marcos Jr courts Japan for regional security, progressive lawmakers in Congress have proposed adding the history of the Philippine’s comfort women to the national school curriculum.

Such a move would ensure that the experiences of these women aren’t forgotten with the passing of time, campaigners say.

Perlita Bulaon, 84, another survivor from Mapaniqui, agrees. She laments how some survivors are reluctant to disclose their experiences, even to their relatives.

“We will never forget what happened to us even if we were young back then. However, we don’t talk about it here. Our children and grandchildren grew up asking why the school has a grave. We don’t answer their questions,” Bulaon said.

Memorialisation has always been a contentious topic within the Philippines. Despite calls to preserve the infamous Red House, the mansion eventually fell into ruins. Only the roof and frame remain.

And in 2018, a comfort women statue installed in Manila Bay was removed amid an outcry from Japanese authorities. Former president Rodrigo Duterte remarked that it is “not the policy of the government to antagonise other nations.” Many other sculptures honouring victims have also been dismantled over the years.

Despite the hurdles, advocacy groups continue to push for remembrance.

In Mapaniqui, the grave at the local school serves as a reminder of the suffering the village and its people endured.

“Our call to the government is to help the grandmothers while they are still alive. Only a few of us remain,” Bulaon said. “We should be able to attain justice.”

Protect yourself and your family by learning more about Global Health Security