Fishing moratorium on Yukon River chinook may be 'too little, too late,' panel hears

A new international agreement on chinook salmon stoked at times emotional debate at the Yukon River Panel meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, this week, and while many appeared to approve of the pact, others seemed to cast doubts.

Duane Aucoin, a member of the Teslin Tlingit Council in the Yukon, said it's taken the collapse of the chinook population to finally do something, but the natural world doesn't work that way.

"One thing we're afraid of is, is this too little, too late?" he said.

"Western policies, Western politics, Western science is what helped get us into this crisis, into this mess. Traditional knowledge will help get us out."

Signed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and the State of Alaska recently, the seven-year agreement sets a new conservation target of 71,000 Canadian-origin Yukon River chinook at the international border. One aspect of the accord that's drawing a lot of attention so far is a fishing moratorium, which, among other things, affects the commercial fishery, long suspected of having an outsized impact on chinook.

Last year, roughly 15,000 fish crossed the border into Canada, far below the former conservation target of at least 42,500 chinook. This season, run size could be even smaller. The latest point estimate of the panel's joint technical committee is 13,000 chinook at the border.

Driving much discussion at this week's meeting is a clause in the agreement that raises the prospect of subsistence and ceremonial harvest, if the species rebounds to the degree that the new conservation target is exceeded.

'Far greater' than new conservation target

Steve Gotch, the Canadian chair of the Yukon River Panel — a Canada/Alaska advisory body on salmon management — said to allow for ceremonial or subsistence harvest under the agreement, the number needs to be "far greater" than 71,000 chinook at the Pilot Station sonar, located near the mouth of the river in Alaska, to account for things like on-route mortality.

"It's probably more in the realm of 90,000 or, if not, 100,000," said Gotch, who's also a senior regional director with DFO in the Yukon.

According to a 2022 report from DFO, 10,000 chinook are required to meet Yukon First Nations' subsistence needs.

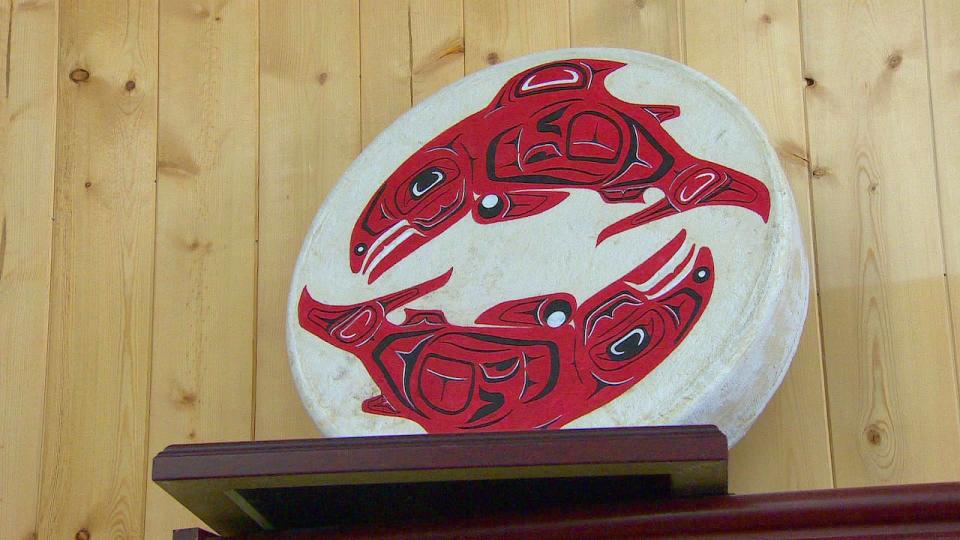

A traditional drum illustrates the importance of chinook salmon to Yukon First Nations' culture and subsistence. (Philippe Morin/CBC)

Panel chairs said this week the goal is to maintain cultural connections while work is underway to rebuild the population.

"Is it going to provide for all Alaskan or Canadian cultural and traditional practices? No, we don't have the fish at this moment, but we do want to look into and explore ways by engaging with those that maintain the knowledge and traditions of their cultures on how we can try and provide for some of that connection to these fish," said U.S. panel chair John Linderman.

"It's safe to say there's more to come, on both sides of the border."

The agreement on chinook hasn't yet been implemented. The Canadian and Alaska governments say that over the coming months they will work with Indigenous nations on that.

'Every fish counts'

Some question how the moratorium could affect cultural harvests.

One Alaska Native panel member said she doubts the agreement will uphold Indigenous rights to fish.

"I don't trust that this agreement will protect those ceremonial uses to the degree that's necessary," said Rhonda Pitka, of Beaver, Alaska. "We've had great losses in our region over the last several years and we haven't had any fish at those potlatches to give."

Pauline Frost, a panel member and chief of the Vuntut Gwitchin Government in the Yukon, said the agreement will only work if everyone does their part along the whole length of the river. If that happens, she said everyone will benefit.

"We have to be consistent in how we manage these resources from here on. Every fish counts," she said.

'We have to be consistent in how we manage these resources,' said Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Chief Pauline Frost, who's also a member of the Yukon River Panel. (Cheryl Kawaja/CBC)

"Because in seven years I don't want to be back at this table talking about a species at risk — because that's a conversation we will have if we don't take drastic action and remove the distrust."

Duane Aucoin of the Teslin Tlingit Council said chinook aren't just facing pressure from fishing in Alaska, and said he's concerned about how the moratorium will be enforced.

"We're also impacted by fishing that goes on on the Yukon side, by even some Yukon First Nation members, who refuse to stop fishing because they say it's their right," he said.

"There can be no rights without responsibility."

Nika Silverfox-Young, a member of the Little Salmon Carmacks First Nation in the Yukon, said she yearns to know how to prepare fish — the traditional way. She wants to be able to pass on those skills to the next generation.

"The loss of salmon is catastrophic to my people and to my Yukon," Silverfox-Young told the panel meeting.

"Now our fish camps are empty, a former shell of what once was great. The ghosts of generations of salmon swim through my nets now. If we do not act immediately, the salmon that swim in our DNA will go to sleep forever.

"To stave off my fears, as well as the youths, we need to bring them home to their streams, where our children of tomorrow can continue our traditions and thrive along with our fish."