The fire-breathing preacher who captivated Detroit’s rich and poor in 1916

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Today’s Free Press Flashback recounts an extended visit to Detroit by the entertaining Billy Sunday, America’s best-known evangelist of the World War I era.

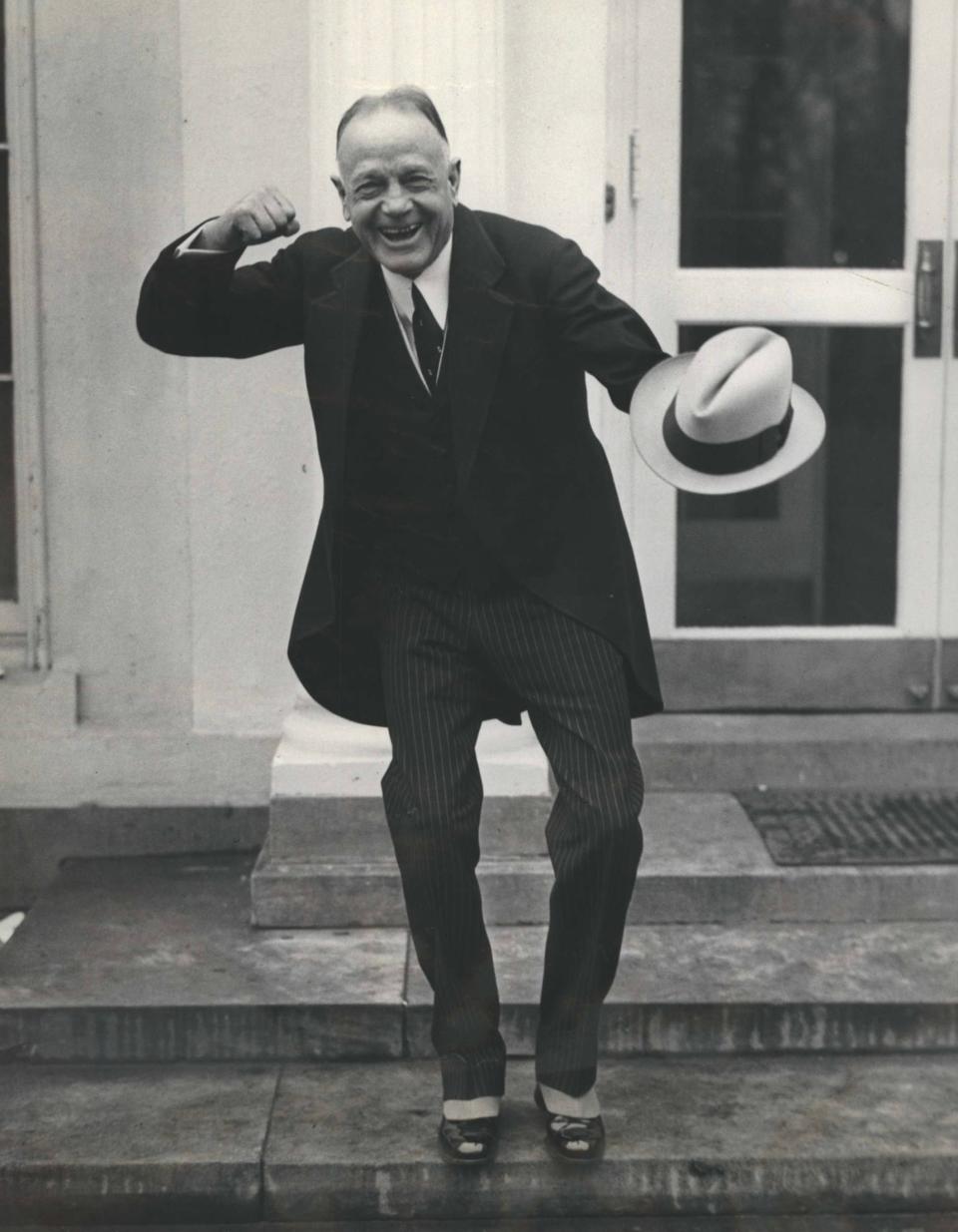

Beginning in the 1890s, Billy Sunday, a former major league baseball player who had experienced a religious conversion, became a fire-and-brimstone preacher with a sense of humor.

Sunday traveled the country, staging revivals in major cities. In 1916, he arrived in booming Detroit, appearing before tens of thousands of people and attracting the attention of such business leaders as J.L. Hudson, Henry Ford and S.S. Kresge as he railed against drinking, smoking and dancing.

Sunday despised dancing.

“I’m against all that rotten, licentious, hell-begotten dance that sends more girls to hell than anything else, and I’ll rip it to hell and gone and back to breakfast,” he yelled at one of his stops in Detroit.

On the stage, he met with much more success than he had on the diamond.

“Measured in terms of claimed converts and net profits,” said The New York Times, Sunday “was the greatest high-pressure and mass conversion Christian evangel that America, or the world, has known.”

No more swearing

Born in Story County, Iowa, in 1862, Sunday played outfield ― in an era when outfielders did not wear gloves ― for the Chicago White Stockings (today’s Chicago Cubs) and the Philadelphia Phillies. He retired in 1890, finishing with a .248 lifetime average and a reputation as a flashy base runner.

Late in his baseball career, Sunday experienced a religious conversion that radically changed his life.

Previously a social drinker and occasional gambler, Sunday now eschewed those habits and any other conduct he deemed immoral, like swearing. Intent on preaching the gospel to anyone who would listen, Sunday asked to be released from his contract to devote himself to full-time missionary work.

His delivery style was aggressive ― he admonished his audience to abandon their immoral ways and devote themselves fully to the demands of the Gospel.

Sunday was small ― 5-foot-8 and 145 pounds ― but he relayed his message with a fervor mostly unmatched by his peers. He would shout for hours at the top of his lungs, often without electric amplification, and pace the stage incessantly.

Sunday blew into Detroit as the city was in the midst of its full-blown auto frenzy. His advance men had worked for months, planning private events to complement the principal celebration.

Workers built a temporary wooden “tabernacle” to house the event at Grindley Field, an athletic ground on the south side of West Forest Avenue between Woodward and Cass. According to the Detroit Times, the building was the largest facility ever to host one of Sunday’s visits.

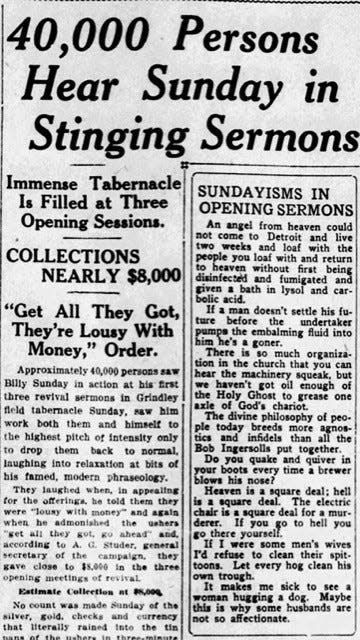

On Sept. 10, 1916, the much-anticipated event began. Sunday performed before about 40,000 people in three appearances.

In his sermons, he attacked one of his favorite vices: demon rum.

“Last year, we spent $2.5 billion for liquor,” Sunday thundered. “The grain that was used for the liquor, if made into loaves, would have paved a street 1,500 miles long, 200 feet wide with every loaf weighing a pound.”

Free Press Flashback: A Detroiter put a statue of Satan in his yard and all hell broke loose

Moving his attention to the evils of smoking, Sunday said, “Last year, we spent about $1.2 billion on tobacco. A man can use tobacco and be a Christian, but he will be a better man if he didn’t.”

The collection taken up that first day alone was estimated at some $8,000 ― equivalent to about $250,000 in 2024.

A gift Cadillac

Sunday rubbed elbows with the common folk and the city’s elite during his time in Detroit. Dime store magnate S.S. Kresge reportedly moved out of his 14-bedroom mansion on Boston Boulevard so Sunday could use it as his battlefield headquarters.

Automaker Henry M. Leland gave him a new $8,000 Cadillac as a “personal thanks offering.”

After meeting with Sunday, Henry Ford said that if Michigan voted for Prohibition, the breweries could be converted to produce denatured alcohol as auto fuel for his cars.

The ex-governor, Detroit’s police chief and various pro baseball players appeared with him at the revivals. And merchant J.L. Hudson was a regular at the sermons.

Sunday was a master at working his audience. The Free Press marveled at the way he paced his performance, gradually achieving “the speed of a machine gun” in his delivery.

“In that first five minutes he created the same state of breathlessness that exists at Navin Field when Ty Cobb comes to bat with a man on third, two out and one run needed to tie in the ninth inning,” the paper reported. “He twisted his lithe and graceful body into a thousand different positions.”

Following his initial service, The Detroit Times noted, “Sixty thousand persons laughed with Billy when he laughed, wept with him as he wept and followed him in all his moods as a bit of metal would follow a powerful magnet.

“He swayed his audiences as a September wind sways the branches, and with his almost matchless oratory he kept the thousands, one moment as quiet as the grave, and the next breaking into the most violent applause, so that the rafters in the monster building were kept trembling.”

One critic was Carl Sandberg

On Sept. 24, Sunday’s wife, Helen Thompson “Ma” Sunday, spoke to a women’s group at the Woodward Avenue Baptist Church. Presenting the same message as her husband, but without much of the vitriol, Mrs. Sunday’s sermon produced 90 converts to come forward, profess their newfound faith and “hit the sawdust trail” ― slang for presenting themselves at the podium to be accepted into the church.

Sunday’s usual routine was to preach six days a week, taking Mondays off to rest. Despite his new vocation, he never lost his love for baseball, and on his first Monday in Detroit, Sunday attended a Tigers game and got a haircut at the Detroit Athletic Club, which granted him complimentary club privileges for the duration of his Detroit stay.

Unlike many of his peers, Sunday did not share in the anti-Catholicism that was common in Protestant circles at the time. In one sermon, the evangelist praised the Catholic Church for its prohibition of divorce, a vice he viewed as dimly as drinking. The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal organization, reciprocated by offering Sunday the temporary use of its clubhouse for office space.

One of Sunday’s contemporaries who viewed the evangelist negatively was poet Carl Sandberg.

Himself a Unitarian, Sandberg was shocked at the incongruity between Jesus’ nonjudgmental message of love and Sunday’s flamboyant rantings. He was so critical that he even wrote a poem titled “Billy Sunday.”

“I’m telling you this Jesus guy wouldn’t stand for the stuff you’re handing out. Jesus played it different,” Sandberg wrote. “I don’t want a lot of gab from a bunkshooter in my religion.”

Sunday’s visit to Detroit took place at the peak of his career. When his dream of national Prohibition became law in 1920, he rejoiced and remained undeterred during the years of violence and corruption that followed. When it was repealed in 1933 ― two years before his death ― Sunday called for its reinstatement.

Sunday died suddenly of a heart attack Nov. 6, 1935, at 71. He went the way he wanted.

Said his wife: “Billy always used to pray, ‘O Lord, when I have to go, please make it quickly.’”

Paul Vachon is a freelance writer who specializes in local history. His most recent book is “Becoming the Motor City: A Timeline of Detroit’s Auto Industry.”

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Billy Sunday, the preacher who captivated Detroit in 1916