A field guide to the legal teams at Kavanaugh's hearing

As the Senate Judiciary Committee reconvenes on Thursday to hear Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations of sexual assault against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, nearly everyone will be bringing a lawyer.

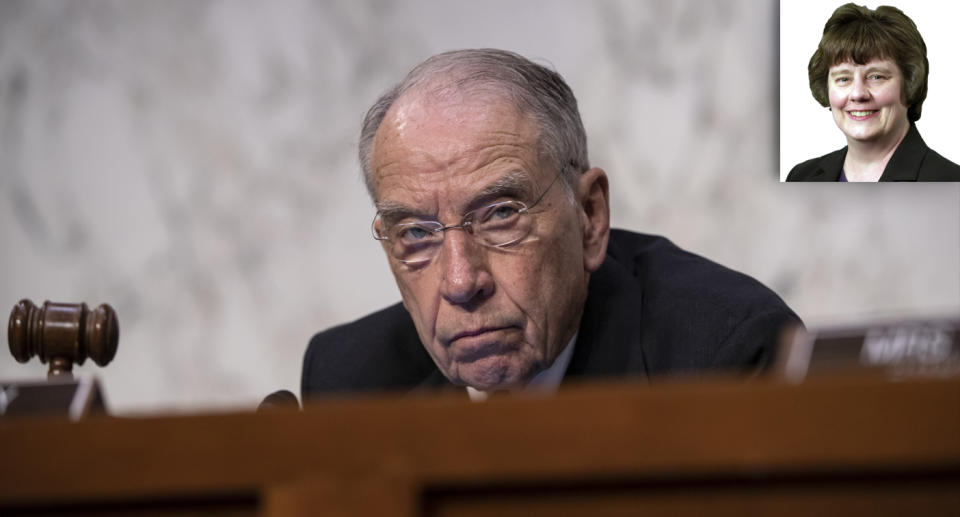

Beneath the bright lights of the hearing room, the witnesses who are scheduled to give testimony, Ford and Kavanaugh, will appear with their legal teams. In addition, the Republican senators on the judiciary committee have chosen to hire a lawyer, a veteran local prosecutor from Arizona, to question the witnesses.

In addition to Ford and Kavanaugh, attorneys also represent several potential witnesses whom Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley appears determined not to call, including at least two women on the growing list of accusers; purported eyewitness Mark Judge; and Judge’s former girlfriend, Elizabeth Rasor.

What follows is a guide to many of the attorneys involved in the hearing or near its periphery.

Rachel Mitchell (for the majority senators) — Republican senators on the Judiciary Committee confirmed on Tuesday that they have hired Mitchell, a local prosecutor from Arizona who specializes in sex crimes, to conduct questioning of Ford and Kavanaugh on their behalf. Mitchell has served as a local prosecutor for 25 years and run the sex crimes division of her office for more than 13 years.

While she is registered as a Republican and a donor to several local Republican campaigns, Mitchell is not well-known outside Arizona. Her appearance in a central role at these hearings is a surprise and a mystery. Mitchell appears to have avoided national politics throughout her career, and it has not emerged how Senate Republicans settled on her or decided to place such a delicate and high-stakes matter in her hands.

While she has stayed away from the national political scene, Mitchell has been witness to turbulent times in Maricopa County. Mitchell joined the Maricopa County Attorneys Office in 1993, the same year Joe Arpaio took over the sheriff’s department and began to fashion it into an instrument of his populist politics. In January 2005, Andrew Thomas, an Arpaio ally, took over as county attorney. Within a week, he had demoted two decorated division chiefs and promoted two lesser-known prosecutors to take their places — including Mitchell, to head the sex crimes unit.

Thomas forged a close alliance with Arpaio, and it cost him. Along with another of his division chiefs, Thomas would eventually be disbarred for ethical violations related to conspiring with Arpaio and prosecuting his perceived enemies on legally deficient charges at his behest. Mitchell would go on to investigate hundreds of sex crime investigations that were botched during Arpaio’s tenure. Other than the 2005 promotion and their overlapping time in office, there is no evidence to suggest that Mitchell played a role in Thomas and Arpaio’s abuse of power. Investigative reports illuminated the clash between Thomas, Arpaio and their acolytes, and the county prosecutors who tried to push back against their unfounded prosecutions; Mitchell does not figure on either side of these confrontations.

While Mitchell has faced criticism for undercharging a predator in at least one case, she generally has a reputation for being fair and nonpolitical, according to many attorneys who have served with or faced her. That reputation, to some observers, only deepens the mystery of why she was picked from obscurity for this politically sensitive role. One theory is the involvement of a local Arizona official in representing the majority’s interests may help to retain the support of Arizona’s senators. Both of that state’s senators are untethered from electoral politics and could be wavering votes; Jeff Flake is retiring and John Kyl, who was recently appointed to fill John McCain’s seat, has pledged not to run for reelection. Flake has expressed consistent reservations about Kavanaugh’s views on executive power. While Kyl served as Kavanaugh’s Sherpa on Capitol Hill before he was appointed to McCain’s Senate seat and was once thought to be a solid yes vote, he has made comments in recent days suggesting he was reevaluating his support for Kavanaugh in light of the new allegations.

Debra Katz and Lisa Banks (for Christine Blasey Ford) —Katz and Banks are co-founders of an employment law firm that specializes in sexual harassment, discrimination and retaliation claims. Ford turned to them for assistance before her name became public.

Katz and Banks have been a force in Washington legal circles representing women, whistleblowers and victims of discrimination in private practice for over a decade. Katz developed a reputation for the unusually thorough and well-researched presentation of the cases she has brought. “I’ve seen demand letters from Debbie that are probably 15 pages long,” Carolyn Lerner, a former head of the Office of Special Counsel, told the Washington Post. That preparation is evident in the documents Ford’s team has released ahead of the hearings — a polygraph exam and sworn declarations from four people Ford confided in about Kavanaugh before he was nominated.

Katz and Banks are active in Democratic politics; they recently canceled a fundraiser they had planned to co-host for Sen. Tammy Baldwin in October to focus on Ford’s case and the Kavanaugh hearings. Banks served as an attorney-advisor to Bill Clinton’s White House counsel in 1999. Right-wing news organizations found video of Katz protesting Jeff Sessions’s confirmation. Republicans have seized on Katz and Banks’s political connections and activism to suggest that their handling of Ford’s case is mere partisan warfare.

However, Katz and Banks are not professional partisans. Their practice consists primarily of trial and appellate advocacy; they do not specialize in congressional investigations and both are likely to find defending a client in a high-stakes, televised hearing before a hostile congressional committee deeply unfamiliar ground.

Michael R. Bromwich (for Christine Blasey Ford) — Bromwich brings real experience handling congressional investigations and national political scandals to Ford’s team. As a young prosecutor, he joined the independent counsel team investigating Iran-Contra, and served as one part of the team that prosecuted Oliver North. He went on to a career as the Justice Department inspector general, and in that role he played a role in a number of hot-button investigations, including the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing and the CIA mole Aldrich Ames. While Katz and Banks are “fine lawyers,” a former Justice Department official told me, “Bromwich has done plenty of congressional investigations and also brings a public relations apparatus with him through a couple people at his consulting firm.”

Bromwich and his team, however, face the difficulty of dividing their time between representing Ford and another high profile client — former Deputy FBI Director Andrew McCabe. While the two matters are in theory separate, both are confrontations with the Trump administration dominating the news this week. In the McCabe matter, the New York Times recently reported the existence of memos written by McCabe that describe Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, who supervises special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, as either seriously or sarcastically suggesting that he wear a wire to record President Trump and also potentially lobby cabinet members to invoke the 25th Amendment. The press reports have further imperiled Rosenstein’s already tenuous job. A statement released by Bromwich’s team, which appeared to confirm the substance of the memos, fueled speculation that the memos were released on McCabe’s behalf. McCabe has been fighting a criminal investigation into the events that led to his termination from the FBI, and a demonstration of his ability to air the Justice Department’s dirty laundry could persuade investigators to lay off him. Rosenstein and Trump are scheduled to meet on Thursday, while the hearing is going on, to discuss his future at the Justice Department. Accordingly, Bromwich and his team appear to have an extremely busy day ahead of them Thursday.

John Clune (for Deborah Ramirez) — A former prosecutor from Colorado who has been in private practice for well over a decade, Clune has long experience representing accusers who lodged high-profile allegations of rape and sexual assault. In 2003, he represented the 19-year-old woman who accused basketball star Kobe Bryant of rape. Ten years later, he represented Erica Kinsman, who said she was raped by Jameis Winston, a high-profile Florida State football player. Last year, he sued Baylor University on behalf of a woman who alleged she had been raped by two football players.

While Clune is used to squaring off with high-profile adversaries on behalf of his clients, representing Ramirez presents an unusual challenge. While Clune may be used to intense media scrutiny from the sports world, he has not been involved in a case directly tied to national politics. Moreover, this is not relatively orderly litigation before a judge. In the Senate, the presiding officers have some flexibility to make up the rules as they go along. Here, Grassley and his staff have decided not to talk to Ramirez and her attorney. Grassley has not indicated that he will call Ramirez to testify, nor has he agreed to her request to have the FBI investigate her allegations as a first step. According to Clune, since Ramirez’s allegations were disclosed in a New Yorker article this weekend, Republican committee staff have repeatedly postponed planned conference calls with him and failed to join calls that went ahead. “The majority staff thus far has refused even to speak with Ms. Ramirez’s counsel,” Clune’s co-counsel William Pittard wrote to Grassley on Sept. 25. That same day, without talking to Clune or Ramirez first, majority staff interviewed Kavanaugh about Ramirez’s allegations; the judiciary committee has since released a transcript. The questions Republicans staffers asked Kavanaugh are based solely on the New Yorker article; in response, he admits that he was acquainted with Ramirez, doesn’t recall being at any parties with her, and denies her specific allegations. In a friendly section of the interview, the Republican staffers ask Kavanaugh whether he’s read a New York Times story that cast doubt on the New Yorker’s piece, which the nominee then eagerly describes.

Clune faces a further challenge because Republicans have seized on a passage in the New Yorker story that raises questions about Clune’s role in bringing Ramirez’s allegations to public light. “The New Yorker story discussed how Ms. Ramirez had a lapse of memory related to this incident until she had several days of conversations with her attorney,” Republican staffers ask Kavanaugh. “Did you read that?” “I did. Six days of—,” Kavanaugh responds before he is interrupted. The exchange is a reference to Ramirez’s initial reluctance to speak with New Yorker reporters Jane Mayer and Ronan Farrow, who pursued her story apparently on the basis of tips from Yale classmates who had heard rumors about the incident. “After six days of carefully assessing her memories and consulting with her attorney,” the New Yorker reporters wrote, “Ramirez said that she felt confident enough of her recollections to say that she remembers Kavanaugh had exposed himself at a drunken dormitory party, thrust his penis in her face, and caused her to touch it without her consent as she pushed him away.” The Republican staffers’ questions to Kavanaugh may indicate that they intend to probe Clune’s role in enabling or encouraging Ramirez to come forward with her allegations.

Beth Wilkinson and Alexandra Walsh (for Brett Kavanaugh) — Wilkinson is one of America’s most high-profile trial lawyers. She began her career in public service, serving posts in the Army, and ultimately taking on a leading role in the prosecution of the Oklahoma City bombers. That experience led to a lucrative private practice where she has led the defense of prestige clients such as Philip Morris, Pfizer, the NFL, and Major League Baseball. Walsh has more direct experience in matters of high-stakes politics. She joined the legal team representing Scooter Libby, former Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, during special counsel Patrick Fitzgerald’s investigation of the Valerie Plame leak. Before entering private practice, Walsh clerked for Judge Merrick Garland on the D.C. Circuit and Justice Stephen Breyer on the Supreme Court. Wilkinson and Walsh recently founded their own firm with a third partner in Los Angeles.

For all their experience, neither Wilkinson nor Walsh appear to have handled many cases involving sexual misconduct nor managed closely watched, televised congressional testimony. Their challenge will be to determine how much they can afford to intervene to fend off hostile questioning on behalf of their client without further damaging his prospects of being confirmed by making it appear he has something significant to hide.

Michael Avenatti (for Julie Swetnick) — Avenatti became a household name during his representation of adult film actress Stormy Daniels and his subsequent flirtation with a presidential campaign. Avenatti revealed on Wednesday that Swetnick alleged in a sworn affidavit that she observed Kavanaugh assaulting other women and that Kavanaugh was present at a party where Swetnick was raped by a series of men. In the transcript released on Wednesday, Republican staffers elicited denials from Kavanaugh based on Avenatti’s public previews of his client’s allegations before she was identified or her affidavit was released; Kavanaugh issued further public denials once Swetnick’s name and allegations became public on Wednesday, but it is not known if the committee staffers have interviewed him in detail about the allegations.

Barbara Van Gelder (for Mark Judge) — Van Gelder is a white-collar criminal defense lawyer in Washington, D.C., who represents Mark Judge, whom both Ford and Swetnick name as eyewitnesses to their assaults. It is unlikely that Judge or Van Gelder will make an appearance at Thursday’s hearing, although calls for Judge to be subpoenaed are growing. Washington Post reporters tracked down Judge, who was hiding out at vacation house in Bethany Beach, Del.

Roberta Kaplan (for Elizabeth Rasor) — Kaplan makes her living as a corporate litigator, but she may be best known for taking a case to the Supreme Court. United States v. Windsor became a landmark on the road to the court’s recognition that the Constitution protects a right for same-sex couples to get married in Obergefell v. Hodges. Rasor went on the record with Farrow and Mayer in their New Yorker piece to contradict Judge’s depiction of his and Kavanaugh’s high school experiences. Rasor said, “Judge had told her ashamedly of an incident that involved him and other boys taking turns having sex with a drunk woman,” a description that appears to echo Swetnick’s account. It’s unlikely that Rasor will appear at Thursday’s hearing, but calls for her testimony may grow if Swetnick is called to testify or if Judge is compelled to appear by subpoena.

_____

More Yahoo News stories on the Supreme Court:

New Kavanaugh allegations don’t change the fact that it’s all about politics

Brett Kavanaugh’s ex-boss: There’s no basis to demand his recusal from Mueller cases

Republican men will be Ford’s interrogators on the Senate Judiciary Committee

Whatever happens to Kavanaugh, Trump has already made 2018 the Year of the Woman

Capitol Hill protests mark rising wave of Kavanaugh opposition

Photos: Anti-Kavanaugh protesters gather on Capitol Hill after 2nd allegation of sexual misconduct