Columbia wants to host NCAA March Madness again. What stands in the way?

Thousands of cities are waiting to be chosen by the NCAA.

Every year, the National Collegiate Athletic Association hosts almost 100 championship events, from the well-known March Madness men’s and women’s basketball tournaments to championships for lacrosse and cross country.

These tournaments can be big business for the cities that host them, bringing in thousands of new visitors and a national spotlight, sometimes on cities that otherwise never see that level of attention.

And Columbia wants in.

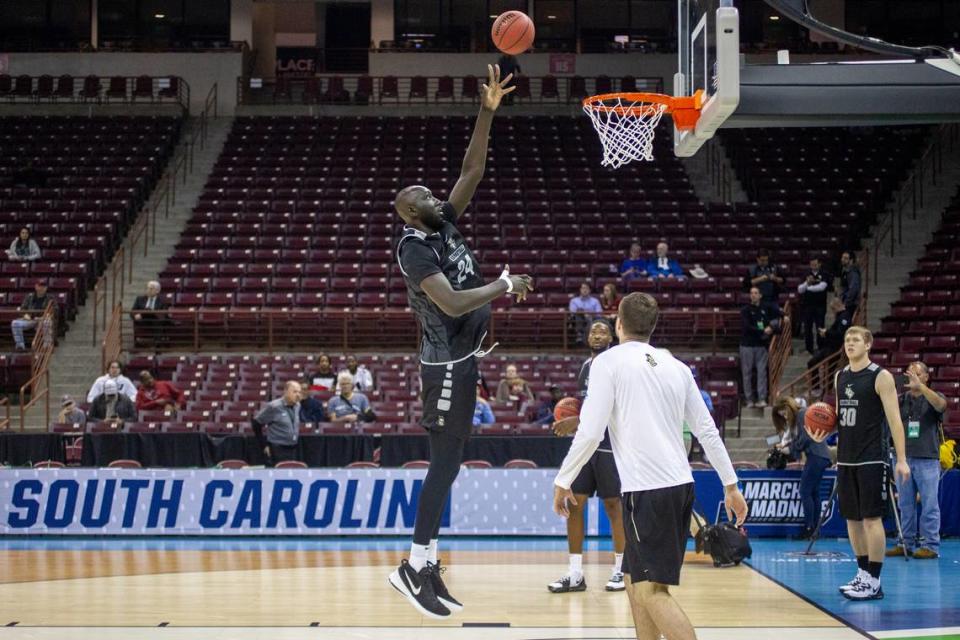

In 2019, the city broke a 50-year streak and was chosen to host a portion of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament for the first time since 1970.

Almost 48,000 tickets were sold for the three games hosted in Columbia that year, and the overall economic impact to Richland and Lexington counties was $11.3 million.

Columbia has again applied to host men’s basketball tournament rounds, as well as the championships for Division II men’s and women’s tennis.

A perfect storm of political willpower and a history of missing out might have helped Columbia cinch the 2019 games. But can the city again prove to the NCAA that it has what’s needed to host again?

How are Columbia’s chances?

Years before the championships happen, cities are pitching themselves to the NCAA, showing off how their arenas, restaurants and hotels are right for the task ahead. Predetermined sites for certain rounds are chosen long before the tournaments begin — Columbia found out in 2017 that it would host part of the 2019 March Madness tournament — so cities have to make their bids early.

Columbia has a few things going for it that leaders think will help the city’s application for future tournaments, which the sports arm of Experience Columbia, the city’s tourism bureau, submitted in early February.

Scott Powers, executive director of Experience Columbia SC Sports, is the mastermind behind the city’s application to the NCAA and he said he feels confident that Columbia has a strong application this time around.

But the city also has some specific limitations to meeting the NCAA’s rules, such as not having enough of the right kind of hotels.

Columbia’s pros

One obvious thing in Columbia’s favor is that it already did this, and well, Powers said. When the city hosted first and second March Madness rounds in 2019, it put on a show and, Powers believes, impressed the NCAA.

There was a fan festival at the convention center, giant banners strung from Colonial Life Arena plus more than 100 street pole signs, restaurants and breweries held special promotions, and organizers provided free parking and shuttles to and from the arena.

“They want to come back to places that do it right,” said Thomas Regan, a University of South Carolina professor who studies the economic impact of sporting and other entertainment events.

Regan said another thing the NCAA would look for is whether a city has enough stuff for a visitor to do that fans will probably have a good time, which Regan thinks Columbia does.

Another intangible Columbia has to offer, though, is a lot of energy around sports.

Mark Nagel, a USC professor who studies sports management and marketing, calls it “psychic income” or “psychic energy.”

Nagel lived in Denver, Colorado, for a few years and explained it as “the Denver Broncos had a huge psychic grip on that community.”

“I think what the NCAA has recognized is that South Carolina is a very strong, not just sports, but a college sports marketplace,” Nagel said.

Cities like Columbia, but also Greenville and Charleston, are heavily driven by college athletics. And that makes the area a good choice for first- and second-round NCAA matchups, because the NCAA can reliably trust that there will be enough fans in the region to produce good ticket sales and high excitement.

Politics might also have helped Columbia secure its historic 2019 bid, Nagel agreed. The NCAA determines its hosts in cycles, so in 2017 the organization announced who would host games for the next four years.

That same year, the NCAA had put a ban on allowing North Carolina to host championship events until state lawmakers repealed a “bathroom bill,” which in part proscribed which bathrooms transgender people would be required to use in public places.

At the same time, South Carolina had just been permitted to start bidding for those events again, after the Confederate flag that flew over the S.C. State House for decades was taken down in 2015, creating a perfect opening for Columbia and other South Carolina cities.

“The political landscape is always concerning for an organization like the NCAA,” Nagel said. “It’s kind of a tricky proposition to know exactly how important certain things politically are, but obviously the NCAA wants to avoid controversy if they can.”

South Carolina still lags behind other states in the region in the number of championship events it was selected for between 2022 and 2026.

During that time frame, North Carolina will have hosted 29 championship events. Georgia will have hosted nine, Tennessee will have hosted eight, and South Carolina will have hosted just seven events, according to NCAA data.

Some hope that leaves South Carolina primed to get a bigger piece of the pie for the 2026-27 and 2027-28 seasons.

Powers agreed it’s hard to know whether the NCAA would choose Columbia over other South Carolina cities.

“Essentially we’re bidding against each other more so than we’re bidding against other cities throughout the country,” Powers said.

Columbia’s challenges

Columbia’s biggest hurdle is its hotels. There are roughly 160 hotels in the Columbia area, but few of them meet the NCAA’s very specific guidelines.

The NCAA wants 10 full-service hotels with in-house food and beverage options, with four meeting rooms of at least 2,000 square feet. And it wants each of the eight teams playing in the tournament rounds to have their own hotel to avoid any bad blood before or after games.

There are only four hotels in the region that meet those requirements, Powers said, and the city hasn’t built any new ones in almost 20 years. The last NCAA-approved full-service hotel that opened in Columbia was the Hilton Columbia Center in 2007.

However, some other Columbia hotels meet the bar to be considered “full-service” by the South Carolina Restaurant and Lodging Association, which says there are six full-service hotels in the area.

Columbia was at one point poised to open three new full-service hotels from private developer Arnold Companies, which owns a large amount of property in downtown Columbia. Owner Ben Arnold had proposed building three full-service hotels in Columbia’s Vista district, close to Colonial Life Arena, that would have added more than 600 hotel rooms this decade. That plan, however, fell through because the developer could not land a deal with the city and county to pay for a public parking garage and a convention center expansion.

The developer is now moving forward with one full-service, luxury hotel in the Vista, expected to bring some 300 new rooms in the arena vicinity in coming years.

Columbia has added hotel rooms elsewhere since it hosted the NCAA, growing from 129 hotels with 11,823 rooms in 2019 to 160 hotels with 13,263 rooms in 2023, according to the lodging association.

“The good news is the NCAA doesn’t draw a hard line,” Powers said.

In 2019, Columbia was able to bend the rules a bit and put eight teams in six hotels. But the NCAA won’t let the city do the same thing again, so every team has to have its own hotel if Columbia expects to win its bid for the 2026-27 or 2027-28 seasons.

But Powers thinks Columbia can still make a case that even if it doesn’t have the exact right hotels, it can make accommodations that the NCAA can live with.

“Your answer in the portal for the bid (can be) yes, no or ‘no, but,’” Powers said. “So just because you have a lot of ‘no, buts’ doesn’t mean you’re not going to have a chance to be successful.”

Powers said his sports tourism team and local hoteliers have been creative in how they’ve presented alternative hotel options to the NCAA. Powers also said that when the NCAA came for a site visit before the 2019 games, officials were surprised by the capabilities of some of Columbia’s limited-service hotels.

“We just had to find a way to meet those requirements for meeting space, for food and that type of thing,” Powers said.

Other challenges include a too-small media room at Colonial Life Arena, though Powers said the arena meets 99% of the NCAA’s requirements.

Whether Columbia’s pros will outweigh its challenges is up to the NCAA, which will announce its host sites for the next cycle of championships in early October.

Why does Columbia want this?

Each of the three March Madness games Columbia hosted in 2019 had an average attendance of about 16,000 people, totaling up to 48,000 spectators in Columbia. But that attendance is peanuts compared to other big events in the Midlands. An average Gamecock football game hosts 77,000 fans, for example.

The difference is that more of the NCAA’s visitors are likely to stay overnight, which means Columbia can expect them to spend more money while they’re here than the average Gamecock football fan.

In 2019, March Madness was expected to have a roughly $9 million economic impact in the area, but it exceeded that guess and brought in more than $11 million.

“It can become very, very impactful for cities that are not as big,” Nagel said.

An event like this would impact Columbia more than it would Atlanta or Miami, for example.

But there are also more intangible benefits to hosting, such as getting the national spotlight and drawing in a lot of new visitors who otherwise might not plan a trip to Columbia.

And securing one big event can help the city secure more in the future. Getting March Madness in 2019 might have helped Columbia get the Premier League game in August, which might in turn help Columbia get more NCAA matchups in the future.

“Hosting those marquee events that move the needle, captures the attention of the community, that allows us to tout those events when we’re going after future events,” Powers said.