How close was Jacksonville to totality during the 1970 solar eclipse?

If you lived in Jacksonville in 1970, you wouldn’t have had to travel far to get in the path of totality for that year's eclipse — unlike the long-distance road trip you’d need to make for this month's total eclipse.

Just a quick jaunt out to the Big Bend, or up to the Okefenokee Swamp would have put you in complete darkness. The prospect brought tourists, TV crews and scientists to North Florida and South Georgia, giving them and the locals a strong shot of eclipse fever.

What was the path of the 1970 eclipse?

The eclipse that year was an 89-mile wide swath of darkness that started in the Pacific, crossed Mexico and the Gulf of Mexico, then came ashore again in Perry, in Florida's Big Bend. It would go over White Springs before sweeping north over Valdosta, Ga., and up to Savannah, Ga. From there it would travel north along the coast to Norfolk, Va., before heading offshore to Nantucket Island and Nova Scotia.

Was there eclipse mania?

There was. Here was the chance to see the sun blotted out by the shadow of the moon. And to see an eclipse so spectacular in the Southeast, the citizens of 1970 were told, they would have to wait all the way until the far future, the year 2017.

In 1969, the head of an amateur astronomers group predicted Jacksonville would be an ideal staging point for 1970’s eclipse watchers. He figured more than a half-million would come. That didn't pan out, but there was still considerable eclipse mania in the area, as locals fashioned eclipse viewers, attended seminars at the George Washington Hotel and boarded chartered buses to chase the darkness.

The 1970 eclipse in Jacksonville

On March 7, 1970, a Saturday, Jacksonville was close to the path of totality — very close — and was told it would see 98.7% of the sun blocked, peaking at 1:21 p.m. It got gloomy enough that neon signs downtown stood out in the cloudy twilight that afternoon.

What about 2024’s eclipse in Jacksonville?

For this year’s eclipse on Monday, by contrast, only about 63% of the sun will be blocked. That basically means you wouldn’t even notice it unless you knew it was happening, said Jack Hewitt, who teaches physics and astronomy at the University of North Florida, which is holding a watch party anyway on campus.

Solar eclipse 2024: Will Florida residents see the solar eclipse? Yes and no. Let us explain

Solar eclipse 2024: What time is the April 8 solar eclipse in Jacksonville? Find out with your ZIP code

What about the eclipse weather?

In 1970, as today, there was always a worry: Florida's famously changeable weather.

In 1970, it turned out those worries were warranted, as a persistent low-pressure system blossomed in the Gulf of Mexico and spread thick clouds along the eclipse's route through the state.

Sure, everything would still turn dark as the eclipse moved over. But the chance to view and record the eclipse — that awe-inspiring movement of the moon shadow over the sun, the sun's corona flaring at the edge? All that would be lost.

In the path of totality, 1970

In anticipation of the eclipse, Florida Gov. Claude Kirk declared Perry, a town of 10,000, the "Eclipse Capital of the World." Fair enough: It would have three minutes and 13 seconds of total darkness, and it would be the first place in the U.S. to witness the event.

On eclipse day, though, the gloomy weather made for crowds much smaller than expected in the Eclipse Capital. Still, the town tripled in size as it drew an estimated 20,000 professional and amateur astronomers from across the world. Some even camped in the woods after Perry’s limited hospitality industry was overwhelmed.

As the eclipse loomed, a busload of schoolchildren from Brevard County sang words from a hit from the previous spring: "Let the sunshine in." But no luck. Heavy clouds obscured even an outline of the sun, and some frustrated astronomers didn't even bother to man the telescopes they'd brought.

Consider the president of a large contingent of Swiss astronomers. He’d traveled all that way to see it, but as the eclipse moved over Perry, he just joined one of his countrymen to play shuffleboard at their motel.

Chasing the eclipse

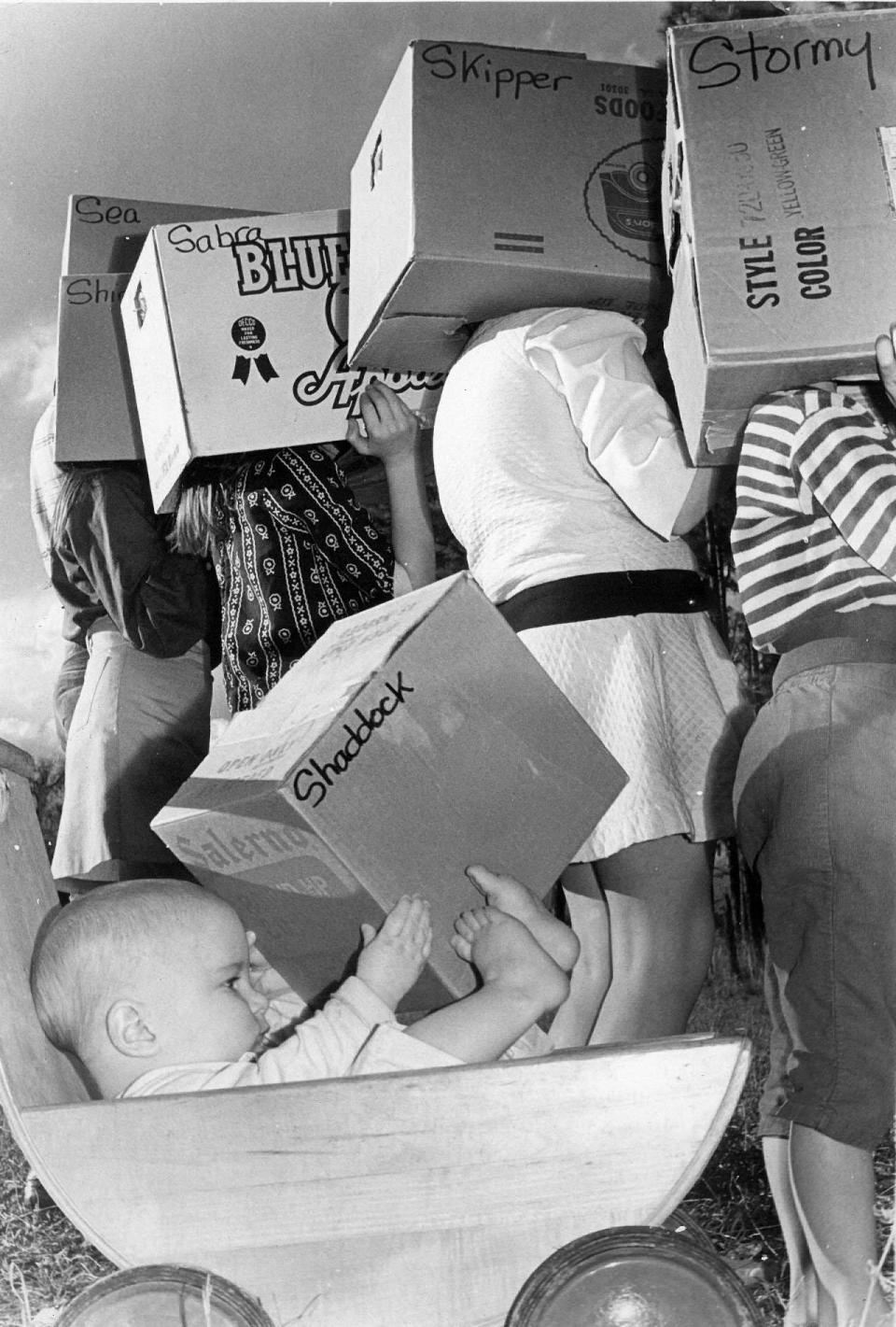

In Jacksonville on eclipse morning, four chartered buses left from the Gator Bowl at 7 a.m., guided by ham-radio operators to wherever the best viewing conditions would be. They ended up in Waycross, in the path of totality. But they couldn’t escape the clouds.

Were any other eclipse events happening?

To be sure, it was a happening down in Gainesville, where students at the University of Florida planned a mid-eclipse love-in and psychedelic rock show, according to organizer Andy Kramer. An interesting side note: As reported by the Times-Union, Kramer was "known locally for the wildest hair on campus."

What about wildlife in Georgia's Okefenokee Swamp?

Many scientists came to the Okefenokee to see how animals would react. A biologist in the refuge told The New York Times that mosquitoes came out as totality loomed, "just like they do at dusk." A flock of 47 buzzards circling overhead flew down to land on cypress branches for the duration. Tree frogs serenaded the darkness.

In nearby Waycross, Gladys Henley, writing for the Jacksonville Journal, noted that "the black thunder-like cloud advanced from the southwest as if it would envelop the entire world. The rest of the horizon all around looked like a mammoth sunset in a soft orange-pink." Birds hushed as darkness came. Then the sun reappeared quickly, "driving back the great black cloud."

What about media coverage of the eclipse?

The major networks were all over the story. For example, at Valdosta State College in South Georgia, CBS TV reporter Nelson Benton, hundreds of onlookers, a loud rock band and a rooster named Brownie came together to witness what the network was hyping as "the solar eclipse of the century."

They were wondering what Brownie would do as darkness descended — "whether he roosts, whether he crows or whether he flies the coop." (Brownie clucked a little, but that's all.)

Benton told anchor Charles Kuralt back at headquarters that the clouds were disappointing, but it was still pretty spectacular as darkness fell. Only the windows in a nearby building were lit. The crowd was hushed. Even the rock band stopped playing.

"Charlie, you've got to be here to believe it," he said as light began reasserting itself. "We're hearing applause from the crowd in the background as we're finding out that the world is not coming to an end."

Did the temperature drop during the eclipse?

Yes. A scientist in Valdosta noted that the temperature there at noon was 77 degrees. It dropped steadily as totality approached, bottoming out at 63.

Interesting info, but so what? Those danged clouds really kind of ruined the eclipse of the century. All that waiting, all that planning ...

"It was a bust," the scientist said.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Solar eclipse: In 1970, eclipse came over North Florida, South Georgia