I got a history tour of the Cincinnati Observatory before the great solar eclipse of 2024

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The total solar eclipse coming April 8 is drawing everyone’s attention to the sky with renewed interest in astronomy. Count me among them.

A recent visit to the Cincinnati Observatory in Mount Lookout reminded me why it is one of the city’s most precious treasures. The observatory, designed by renowned Cincinnati architect Samuel Hannaford in 1873, is described as “a picturesque jewel-box of a building capped by a silver dome.” But it’s the historic telescopes, once among the largest in the country, that are the true gems.

John Ventre, the observatory historian, led my family on a tour of the facility and a peek through the extraordinary telescopes to view the universe. It was an awesome experience, a lesson in history and the marvel of ideas.

Ventre told us the history of the observatory as we went along. He is the co-author, along with Stella Cottam, of a new book, “Cincinnati Observatory: Its Critical Role in the Birth and Evolution of Astronomy in America.” It is presented as a textbook, but it’s an engaging read about some fascinating Cincinnati history.

Our History: 1800s Cincinnati comes to life in this collection of rare photos

Cincinnati built America’s first major observatory

In the 1840s, there were about 130 operating observatories in Europe, but only a dozen or so in America, all of them small, private or associated with a school rather than being professional, said Ventre.

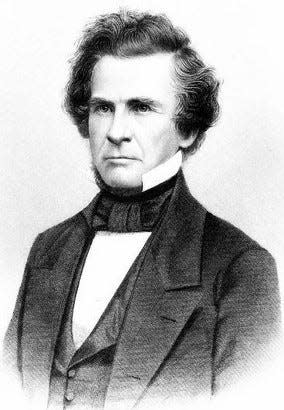

Everything changed due to the efforts of one man: Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel.

Mitchel was born about 1809 in Union County, Kentucky, and was raised in Lebanon, Ohio. Educated at West Point, he returned to the area and in 1836 was offered a position at Cincinnati College to teach mathematics, civil engineering and mechanics. With a keen interest in astronomy, he added lectures on that as well. They were so popular that students started bringing their families along to hear him.

“He was a dynamic lecturer, not common for the day,” Ventre said.

Mitchel also used some clever visual aids. A woman in the audience recalled: “Mr. Mitchel used to prepare his own illustrations by picking out the constellation in thin paper with a large pin; he would nail the paper to a frame and put a candle behind it, and then explain the heavens to us.”

In 1842, Mitchel gave a lecture on the solar system. The overflowing crowds led to it moving to Wesley Chapel on Fifth Street, then the largest venue in the West, seating 1,200.

At the lecture, Mitchel proposed the construction of an observatory in Cincinnati. He hoped to raise $7,500 (about $240,000 today) by selling shares in the Cincinnati Astronomical Society for $25 each ($800 now).

The 300 stockholders included a cross-section of Cincinnatians: attorneys, doctors, carpenters, teachers, blacksmiths, clerks and a steamboat captain.

John Quincy Adams laid the cornerstone in 1843

The Cincinnati Astronomical Society, with Judge Jacob Burnet as president, sent Mitchel to Europe with $1,000 ($32,000 now) to purchase a telescope.

He found an 11-inch Merz and Mahler lens in Munich, Bavaria, that had been ground but not installed. Mitchel had it fitted into a brass and mahogany telescope, then shipped it back to Cincinnati. Wealthy landowner Nicholas Longworth donated 4 acres on Mount Ida (now known as Mount Adams) to place the observatory on a high spot.

Mitchel invited former President John Quincy Adams, who had advocated for a national observatory, to come to Cincinnati to lay the cornerstone. The 76-year-old took a 1,000-mile journey by canal boat and carriage to Cincinnati for the occasion.

On Nov. 9, 1843, a parade marched up the hill in a torrential downpour to place the cornerstone, but it was too wet for Adams’ speech. He gave it the next day at Wesley Chapel. Ventre and Cottam’s book reprints the entire text of what was the former president’s last public speech, filling up 36 pages. In gratitude to Adams’ visit, the citizens renamed Mount Ida in his honor – Mount Adams.

“The telescope (Mitchel) acquired matched or surpassed all the other telescopes in Europe except one,” Ventre said.

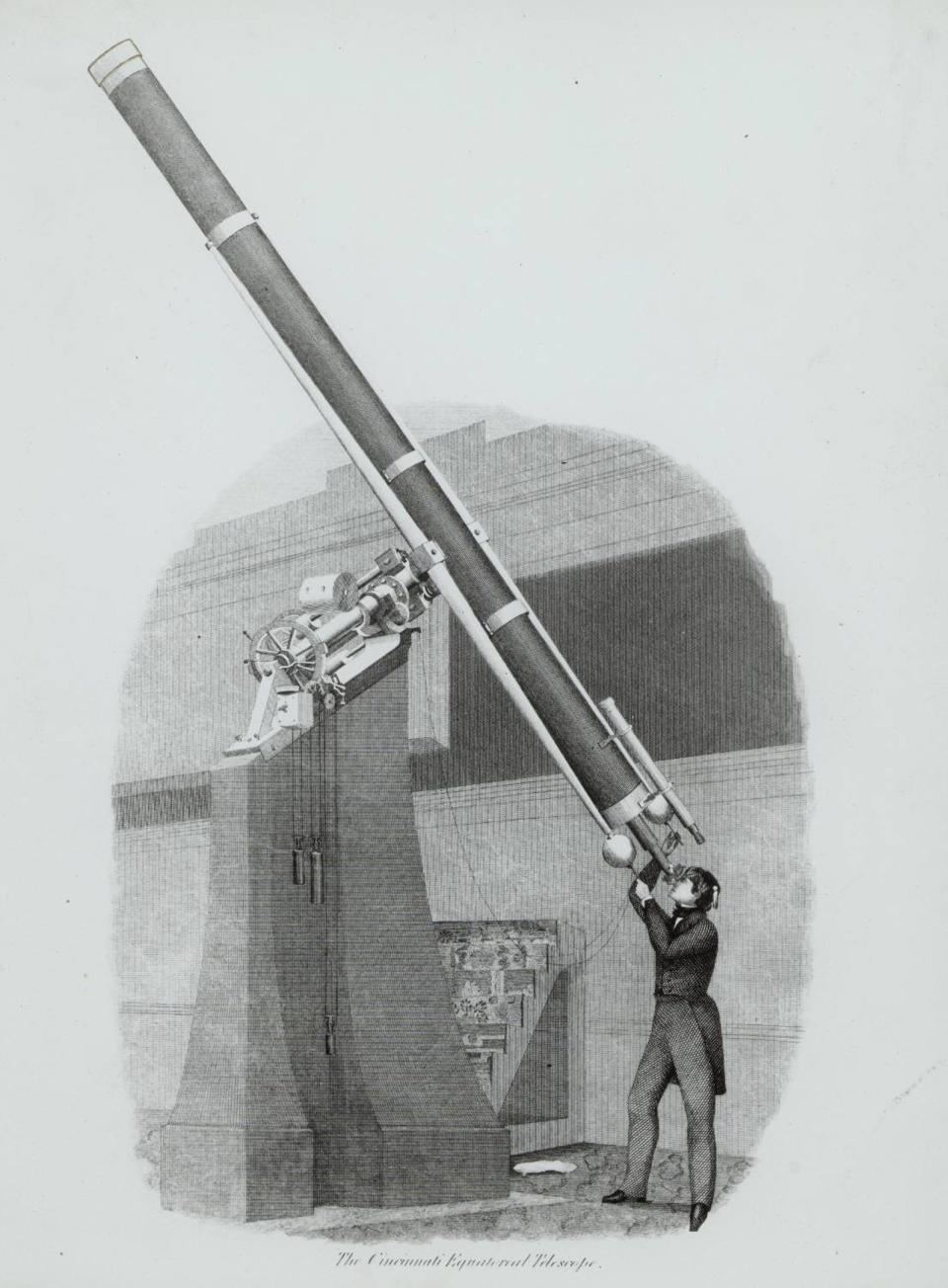

On April 14, 1845, when the Merz and Mahler telescope saw “first light,” an astronomy term for its first view, it was the largest telescope in the Western Hemisphere.

Cincinnati Observatory is the oldest operating professional observatory in the U.S.

Relocating the observatory to Mount Lookout

Within a few decades, the Cincinnati air was foul with soot and smoke from the growing city. So plans were made to move the observatory. First the then-new University of Cincinnati, which was organized in 1871, acquired it. With UC taking ownership of the observatory, telescope and records, the Cincinnati Astronomical Society ceased to exist.

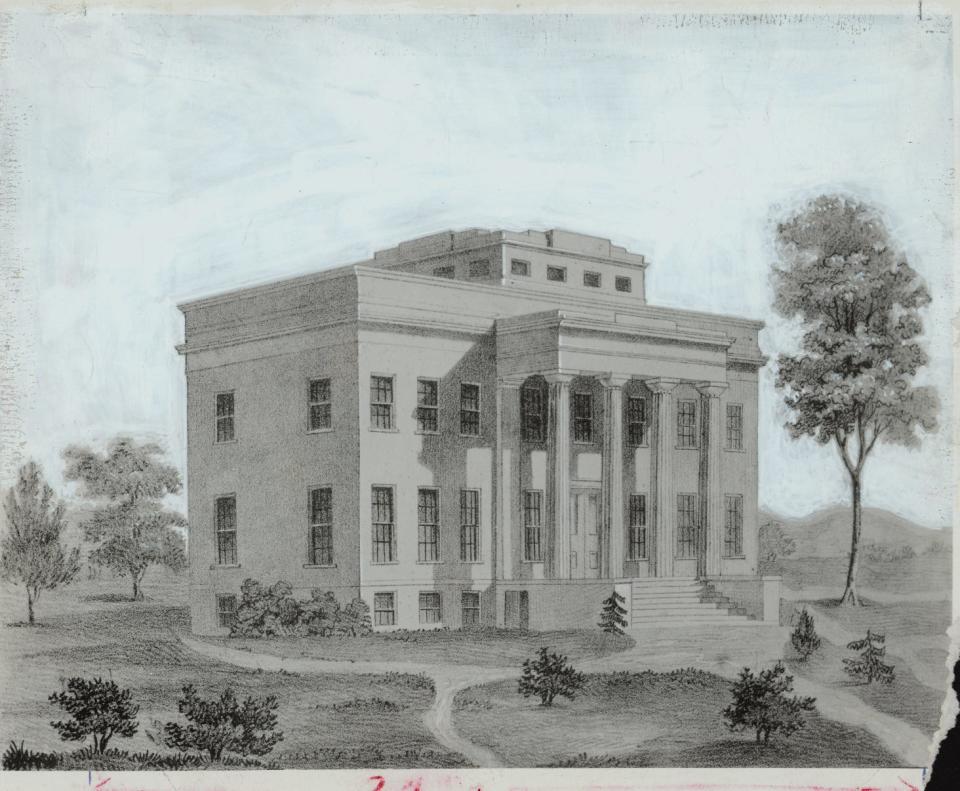

John Kilgour, a banker whose father was a charter member of the society, donated 4 acres of land near Hyde Park for the observatory. The area was then dubbed Mount Lookout. He also gave $10,000 ($259,000 today) to build a new observatory, a Greek Revival design by Hannaford.

Construction of the new observatory began in 1873 and it opened in 1875. The original cornerstone laid by Adams was set into the corner of the new building, where it is today.

A second, larger telescope with a 16-inch Alvan Clark and Son refractor, was bought in 1904 and installed in the observatory. A second building, named after Mitchel, was built for the original microscope.

Travel back in time: What was it like to live in Cincinnati in the 1870s?

Saving the historic observatory for the future

In the 1990s, the Cincinnati Observatory was nearly history.

The observatory buildings were in deplorable shape, Ventre said. There were rumors UC wanted to close the observatory, sell the land and put up condos. Concerned neighbors and citizens, including Ventre, formed a Save the Observatory group. UC decided to keep the observatory and offered to pony up money for waterproofing, the costliest part of the $2.5 million restoration.

“The general goal was to make it a working, functional late-1800 astronomical observatory and restore everything as close as practicable to its working condition,” Ventre said.

Today you can learn about the history of the observatory at a small museum and go up to look through the eyepiece of the telescopes for yourself.

What’s remarkable is both telescopes are virtually the same as they were originally. There is no electricity needed. The aluminum shudders of the dome are opened for viewing by pulling a rope. Everything is carefully balanced and turns on gears.

Ventre explained one feature of the large Alvin Clark telescope that much impressed me for its ingenuity.

“There’s about a 400-pound weight in the pier of the telescope,” he said. “By cranking up the weight and letting gravity pull down or drop the weight, that’s kinetic energy. That energy, via various series of chains and gears, moves the telescope at the rate of one revolution per day in the opposite direction that the Earth rotates. Therefore, the byproduct of that, as you point the telescope at a celestial object, the telescope will mechanically track and stay on that target as the Earth turns on its axis in rotation.”

“Even today, it’s a precision machine,” Ventre added. “It’s awesome.”

When my family and I had the opportunity to observe the universe through the telescopes – the same way Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel did more than 175 years ago – we saw the moon, crystal clear, with perfect circles cratering the surface. We saw caramel-colored Jupiter and four of its moons, approximately 400 million miles away.

Looking through the past to see the future.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Solar eclipse: A perfect time to explore the Cincinnati Observatory