Caprock Chronicles: The historic treasures of Blanco Canyon, part two

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s Note: Jack Becker is the editor of Caprock Chronicles and is a Librarian Emeritus from Texas Tech University. He can be reached at jack.becker@ttu.edu. Today’s article about treasure in Blanco Canyon is the second of a two-part series by frequent contributor Chuck Lanehart, Lubbock attorney and award-winning Western history writer.

In 1990, archeologist Don Blakeslee set out to find evidence of Francisco Coronado’s route through the Llano Estacado. He obtained a Wichita State University grant, and in 1991 obtained a grant from the Herrington foundation, which funded fieldwork in 1992-93. Participants included noted archeologists Waldo and Mildred Wedel from the Smithsonian Institute and Jack Hughes from West Texas State University (now West Texas A&M University).

“I concluded Coronado’s campsites lay on the eastern side of the Llano Estacado between about Quitaque and Yellowhouse Canyon,” said Blakeslee. “In part of my research, I visited Floydada, and Nancy (Marble) asked Jimmy (Owens) to give me a tour of Blanco Canyon. At the end of it, Jimmy said that if the camp was in that canyon, he would find it. About a year later, he had found a possible Coronado artifact, and by the time I got to visit, he had a second one, of copper, which clinched the deal.”

Owens had found copper crossbow boltheads (arrowheads) which fit the pattern of those confirmed from Coronado's earlier encampment near present-day Albuquerque.

Then, on Labor Day weekend in 1994, Owens showed Blakeslee and Jay Blaine—metal artifact expert—the contents of his junk box, and Jay spotted an ancient Spanish horseshoe nail. “When Jimmy told us he had found it a mile or so down the canyon two years before, our faces showed some disbelief, so the next morning he went to the spot and came back with another crossbow bolthead. That spot turned out to be a part of the main camp.”

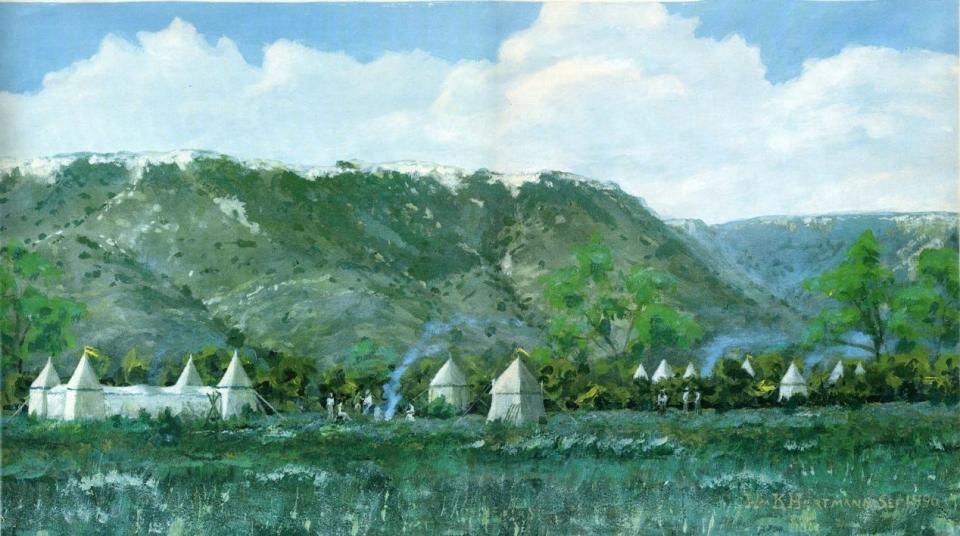

Archeological excavation at the site took place again in 1995, utilizing Wichita State University students. Owens assisted, and Blakeslee said the group enjoyed plenty of West Texas hospitality from the locals.

A few pottery remnants characteristic of Coronado-era New Mexico pueblos were unearthed, though opinions differ about whether Blanco Canyon was the site of the notorious hail storm which destroyed all of the army’s crockery. Blakeslee believes the hail storm campsite is nearby in another canyon.

But there is no question the area was a campground for Coronado’s army. Hundreds of artifacts were unearthed, including many more copper crossbow boltheads, coins, jewelry, horse gear and other odds and ends. Someone discovered two copper aglets (metal tubes which fit tightly around each end of a shoelace). By researching Coronado’s records, Blakeslee’s crew identified the owner of the aglets as the captain of the infantry unit.

Blakeslee directed the survey of an area he suspected was occupied by harquebusiers (carbine-armed cavalry) and found three 53 caliber musket balls. “Three 53 caliber pieces is what the Spaniards used (along with a larger ball) in what is called a buck-and-ball load,” Blakeslee explained.

The archeologists cleared mesquite from a swath 20 meters wide and 200 meters long and mapped the campsite. “It yielded two main concentrations of Spanish material that turned out to be two sides of a triangle,” Blakeslee said. “Then once we figured out that the infantry units were in a line at the upstream end, we were able to determine that the high-ranking horsemen occupied the other end. That led us to find the corner at the downstream end and to see that there was a line of material heading toward the infantry line.” He directed a metal-detector search of the area, which turned up a Spanish nail that had been hammered into mesquite, evidence it was used to tether a horse.

The Blanco Canyon area which yielded the historic Coronado relics was soon named the “Jimmy Owens Site” in his honor. Jimmy died, age 47, in 1998.

The Owens Site is situated southeast of Floydada in one of the steeper, more entrenched ravines that run through the area. The site is on private land and cannot be accessed without permission. Blakeslee is not interested in further archeological digs in Blanco Canyon related to the Coronado expedition and would prefer to leave the site intact.

So, what is the archeological significance of the Blanco Canyon campsite, other than to prove Coronado slept here? Blakeslee says the site serves to understand Coronado’s route through the Staked Plains. “Some people thought he was north, and others south. Having the exact route allows us to make sense of what was written in some of the (Coronado expedition) documents and passages that otherwise were obscure.”

Coronado continued northward from Blanco Canyon to the banks of the Arkansas River in Kansas, where the explorer found only small communities of naked people living in grass huts. His quest to find the Seven Cities of Cibola and great wealth was a dismal failure.

The conquistador soon ended his expedition and returned to Mexico, disgraced. Departing with little impact on the Llano Estacado, Coronado left behind the treasures of Blanco Canyon, the only physical evidence of his Texas travels.

Many of Blanco Canyon’s Spanish treasures, including the gauntlet, remain on display at the Floyd County Historical Museum in Floydada.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Caprock Chronicles: The historic treasures of Blanco Canyon, part two