1878 was the last total eclipse in Texas. Fort Worth erupted in shouts heard a mile away.

Our Uniquely Fort Worth stories celebrate what we love most about Cowtown, its history & culture. Story suggestion? Editors@star-telegram.com.

It wasn’t looking good.

An exceedingly rare total eclipse of the sun was only two days away, and a team of scientists had arrived in Fort Worth from thousands of miles away to use the most modern equipment of the day to observe it.

But showers and clouds on July 27, 1878, caused “some anxiety” as to what the weather would do on July 29, when Fort Worth would be shrouded in darkness for 2 minutes and 42 seconds, according to dispatches from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that appeared in the Galveston Daily News.

In less than a week, Fort Worth will once again be blanketed in darkness — for exactly 2 minutes and 24 seconds — as it sits inside the path of totality for the April 8 total solar eclipse. Many Texas towns on the enviable spine of totality have parlayed their good fortune as willing hosts to this celestial party.

Weather is certainly a concern this time around, since North Texas sees more severe storms this time of year. In the National Weather Service’s first weather forecast for the big day, it gives a 25% chance that clouds may dampen the party.

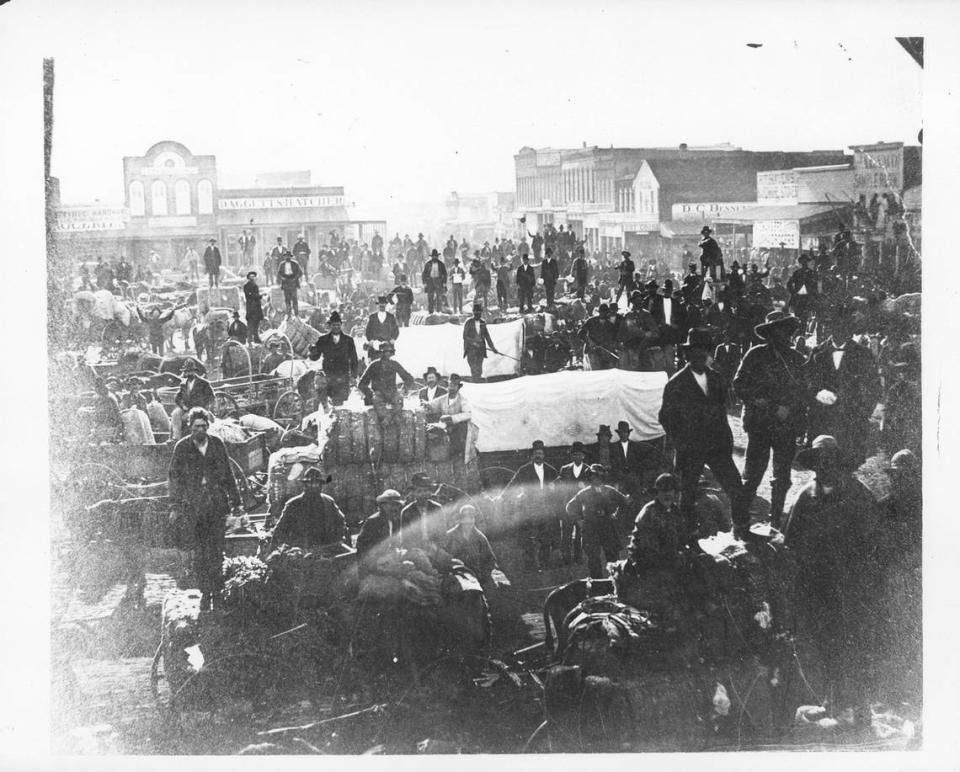

There was no weather service in 1878. Fort Worth was still a small town at the time, having incorporated just four years earlier when the population was under 1,000. The first streetcar was only 2 years old, as was the town’s first artesian well.

The scientists, who came from universities and observatories in Harvard College, St. Louis and Rhode Island, set up a “fully equipped observatory” with 26 instruments in the yard of S.W. Lomax, who lived on a hill on the eastern part of town.

On the big day, heavy clouds that had obscured the sky from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. slowly moved away, allowing five photos of the eclipse (“two with polarizing apparatus”) and numerous notes, drawings and measurements “of great scientific value,” showing the “specific character of gas or air near the sun’s edge.”

When Fort Worth started to go dark at 3:11 p.m., the temperature was 93 degrees. By 4:14 p.m., at the moment of totality, it was 80 degrees.

“The darkness was not so great as to prevent reading, but objects 200 yards off could not be distinguished easily,” the Star-Telegram dispatched. “Fowls roosted on the ground where they were feeding when the darkness came on rapidly.”

For April 8, a scientist from N.C. State University and a team of observers will be in Fort Worth, specifically at the Fort Worth Zoo, to record how the dimming skies might affect the animals. A similar experiment was conducted during the 2017 eclipse at Riverbanks Zoo in Columbia, South Carolina. The volunteers will see if behavior seven years ago will hold true in 2024. Will primates still think it’s bedtime? Will the flamingos agitate? Will the tortoises find the mood for a little love?

At the moment of totality in 1878, continuous shouts were heard from in town about a mile away from Lomax’s farm. Lightning in the distance to the south added to “grand scene of an event which goes into scientific history.”

“The scene during the observation was one that would remind an old veteran of a decisive moment of battle, when all are trained to duty at respective points,” the Star-Telegram wrote, describing the scientists’ work. “Between the time of the first and last contact, no noise or word was heard, save the slow measured dictates of the observers to their recorders.”

Here’s the full article that appeared in the newspaper on the day after the eclipse: