Tom Wilkinson Was the Kind of Actor You Never Forget

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

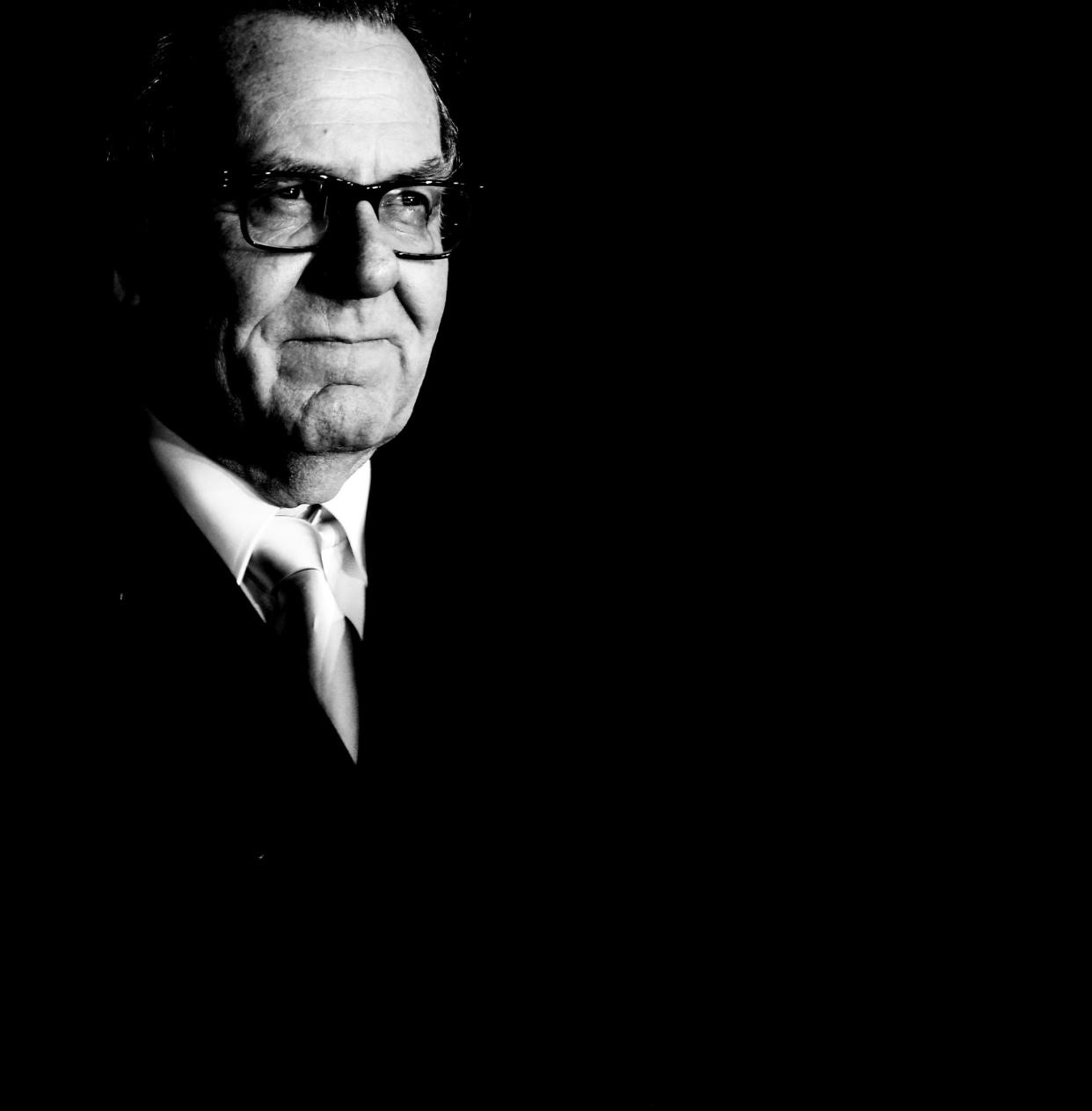

Rune Hellestad - Corbis/Getty Images

In Tony Gilroy’s 2007 legal thriller Michael Clayton, the British actor Tom Wilkinson plays Arthur Edens, a star litigator with bipolar disorder. Edens is full of enough bombast that his sentences and truthfully deranged speeches feel like their own character in the movie. Even though he’s speaking a mile a minute, flailing his arms at times, and makes rash decisions throughout the picture, he’s also operating like a walking truth serum; even at his most overwhelmed, he’s righteously accurate about his job — defending a grimly capitalist company that his corporate-behemoth law firm has asked him to back — and therefore, his very existence as an American male beholden to his work.

Edens spars intensely with Michael, played by George Clooney, prodding him by merely asking questions about himself: “Is that the answer to the multiple choice of me?” It takes time for Michael to see how right Edens is about everything, but in these moments, you feel his anger emanating from Wilkinson. Michael may be the movie’s protagonist, but Wilkinson’s Edens is its conscience and bleeding heart. His presence is what makes that film increasingly dark in worldview and feeling; he makes our hearts bigger before sinking them.

Tom Wilkinson, who died at the age of 75 on Saturday, was an actor who had the ability to steal every picture that he was in, and he sometimes did. An alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, Wilkinson spent the 80’s and 90’s popping up in small roles in a wide range of films. (Look out for him as the appeals prosecutor in 1993's In the Name of the Father). It wasn’t until after 1997’s The Full Monty, the British crowd-pleaser about six working-class men who start a strip-tease act, that Wilkinson began regularly popping up in Hollywood movies. The succession of films that Wilkinson went on to shine in are so dramatically different, in succession, that it almost felt like he was deliberately showing off his still-underappreciated range. (After The Full Monty, he was in Rush Hour as a British diplomat who’s secretly the top crime boss in Hong Kong; although Jackie Chan and Chris Tucker’s absurdity is that movie’s main attraction, Wilkinson’s work as the villain is genuinely and surprisingly chilling, especially when he’s hitting Chan in the head with a suitcase.)

Wilkinson was an imposing man; directors would keep his big chest in the frame so you could see the paunch he had, and the large pants he would wear. He had the face of a weary and careful man, not someone excitable. He was never a looker, but he was usually dressed nicely onscreen, which added to his aura of sincerity. (I’m a fan of his collared shirts in Michael Clayton. He doesn’t look like Sydney Pollack’s Marty Bach, the managing partner at his and Michael's firm. Instead, he’s a little bit more unkempt, a subtle nod to the character’s mental illness.) He was someone who could play a moneyed elitist, but had the face of someone detached from money, or emboldened by it to the point of villainy. In Batman Begins, he plays another crime boss, this time controlling Gotham’s streets; in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, he’s a doctor who is essentially playing God. Wilkinson is exceptional in that one; at first, there isn’t a reason for him inventing the procedure that Jim Carrey decides to use to get rid of the memories he has of Kate Winslet’s character, but when it’s revealed that Wilkinson’s character had an affair with Kirsten Dunst that she no longer remembers, a banal role becomes a meditation on abuse of power. And Wilkinson plays it shiveringly.

Character actors, and the joy we get from watching them show up—and show everyone else up, even in a terrific movie—make film fandom come alive. Wilkinson is all I can think about when I think of Michael Clayton, despite Clooney’s lead performance. Anytime I’d read a cast list and see that Wilkinson was in a movie, I’d be overjoyed that I’d get a chance to see him work. (In Selma, a movie that I find somewhat didactic and dry, Wilkinson still shines as a frustrating and depressingly moderate President Lyndon B. Johnson). Yes, stars are why we go to the movies, but character actors are who we talk about at dinner at The Odeon afterwards.

Wilkinson will always be known for two major roles: One is Michael Clayton and Todd Field’s 2001 family drama In The Bedroom. Both feature men on the precipice of a major event; both feature men who have become world weary and possessed with anger that seethes underneath their affability. When Clooney’s Michael Clayton catches up to Edens in Soho—he’s carrying a large bag of baguettes, looking like he’s stolen them—and pleads with him to remember who they work for, Edens sizes him up. “Michael, I have a deep affection for you. You live a rich and interesting life. You’re a bagman, not an attorney.” That was Wilkinson in Michael Clayton: you didn’t know if he would be crazily lucid or lucidly insane.

Despite that movie becoming an anti-capitalist staple and an American movie classic, my favorite performance from him is In the Bedroom. Wilkinson plays a grieving father and a husband to an equally devastated Sissy Spacek. In the confrontation that the whole movie builds toward, he blames her for their son’s death, screaming “You are so controlling, so overbearing… even when he was a kid, you were telling him how he was always wrong.” Wilkinson’s character is in pain, and because he became all of his characters, he was in pain. His eyes go from light to dead by the end of the movie; we can’t take ours off him.

Originally Appeared on GQ