Sri Lanka Has a New Walking Trail With Wild Forests and Centuries-old Wellness Retreats — What to Know

The hiking path covers 186 miles, visiting towns and locations rarely seen by travelers previously.

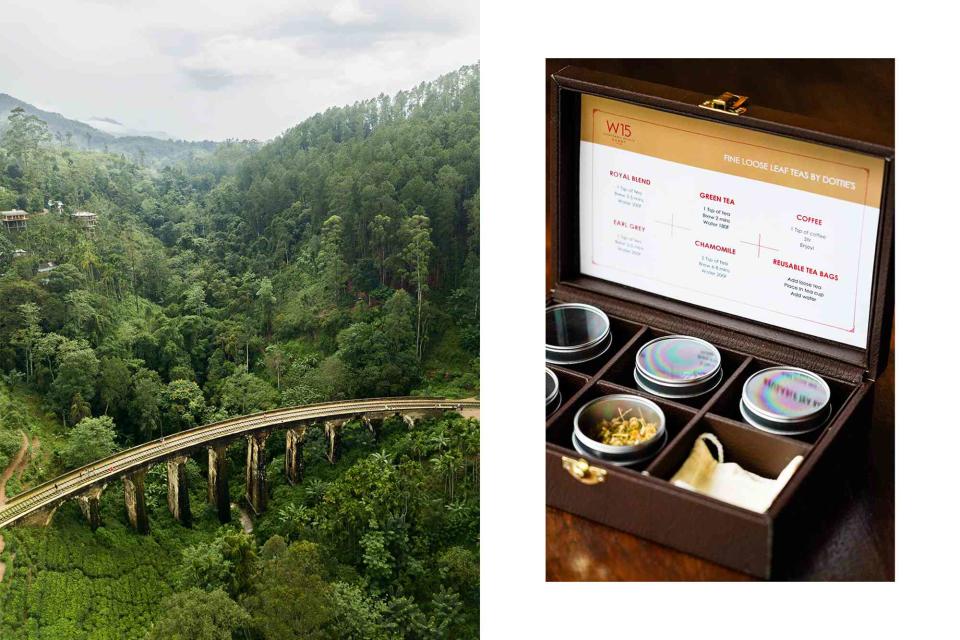

From left: iStockphoto/Getty Images; Courtesy of W15 Hanthana

From left: The Nine Arch Bridge, in the central highlands of Sri Lanka; the loose-leaf selection at the W15 Hanthana Estate, in Kandy.Heavy clouds rolled overhead, clearing out the day’s humidity in Sri Lanka’s central highlands. Below a forested hillside, tea pickers in colorful saris moved among rows of electric-green bushes, as if the scene were set to high contrast. In the distance, plumes of smoke carried the scent of roasting tea leaves.

I was walking the Pekoe Trail, a long-distance hiking path that opened in Sri Lanka last year. Largely made up of existing paths used to travel between tea fields and factories, it winds 186 miles through estates and national parks. The trail, which connects 80 hamlets and villages that see few foreign visitors, was designed to bolster Sri Lanka’s tourism industry in the aftermath of the terrorist bombings that took place in the capital, Colombo, on Easter Day 2019.

More a walking holiday than a backpacking expedition, the entire trail is designed to take a laid-back 22 days, with hikers covering an average of nine miles each day. For those who don’t have three weeks to spare, it’s possible to link up separate sections with the help of a guide and driver, as I did on my five-day trip.

Courtesy of Thotalagala

From left: One of the seven suites at Thotalagala, a resort in Haputale, Sri Lanka; tea with a view at Thotalagala,After arriving in Colombo, I boarded a three-hour train to the ancient city of Kandy, where the trail starts. I spent my first night at the 10-suite W15 Hanthana, where a wraparound veranda overlooked misty mountains topped with stupas and temples. The next morning, after a late breakfast of string hoppers (rice noodles) and curry, I set out on the first segment on my route: 7.5 miles of easy dirt road that cut through colorful villages and the Hanthana mountain range, a popular hiking spot, before ending in the small town of Galaha.

I was accompanied by Miguel Cuñat, the sustainable-tourism consultant who designed the trail. “You know that saying ‘To understand an island’s soul, head to its interior?’” he asked me as we ate mangoes from a roadside stand during one of our breaks. I knew what he meant. Like many visitors to Sri Lanka, I had only spent time along the beautiful coastline, and it wasn’t until this hike that I began to sense the island’s true character.

On my second day, Cuñat and I walked uphill through a steep pine forest and then followed a ridge that overlooked the Knuckles mountain range and the snaking Mahaweli River. Thick fog in the distance signaled the looming monsoons. Two hours later, the forest opened up to the Loolecondera, Sri Lanka’s first tea estate, which dates back to 1867.

Courtesy of W15 Hanthana

The piano room and library at W15 Hanthana, near the start of the Pekoe Trail.From there it was a 56-mile drive to Goatfell, a beautiful bungalow that overlooks Ceylon tea fields. I dipped my tired legs into the infinity pool, then read by the living-room fire as the rains rolled in.

The next morning, it was a quick drive to Nuwara Eliya, a picturesque city that is a popular getaway for many Sri Lankans. We hiked six miles through a tableau that felt like the quintessential image of the countryside. Women moved through tea fields, gently plucking only the youngest buds and leaves from each branch to assure the highest quality of Ceylon black tea. Many of the tea pickers are descendants of the indentured South Indians brought over by the British colonists in the 19th century, and the work is still punishing. Under wages set by the government, they must pick about 40 pounds of tea each day to earn just over $3.

While Nuwara Eliya is the official end of the Pekoe Trail, hikers can follow the route in any order they like. So, after a tea break, we drove 60 minutes to Horton Plains National Park, where a windswept plain was circled by a cloud forest. We strolled under a troop of bear monkeys swinging from trees before the dense canopy opened up to a switchback called the Devil’s Staircase, which overlooks the lush Udaweriya Valley.

That night we slept at Thotalagala, a seven-suite retreat in Haputale where Thomas Lipton, the Scottish merchant, began his Lipton Tea empire in the late 19th century. The next morning, I took a tuk-tuk to a panoramic overlook called Lipton’s Seat, where Sir Thomas is said to have sipped tea and looked out over his estate. The view has not changed much.

Courtesy of The Pekoe Trail

Hikers on the Pekoe Trail, which was designed to boost tourism.For our final hike, we drove to a modest village, Makulella, then climbed through a eucalyptus forest to a ridge dotted with Buddhist temples and waterfalls until we reached the Nine Arch Bridge. The famous viaduct turned out to be just as dramatic in real life as it is in photos. While other tourists arrived in tuk-tuks, it was satisfying to approach the bridge on foot, alongside children in starched school uniforms.

The people behind the Tourism Resilience Project — which established the trail and is funded by the European Union and the U.S. Agency for International Development — hope it can empower villagers to make a living from the new route, perhaps by operating a juice bar or tea-tasting room for hikers. “We want the people living and working there to feel like they’re a part of it,” said Vishadini Fernando, a project manager. The vision includes giving visitors more chances to learn from locals.

It was just this kind of understanding that soothed me during the night I spent at Thotalagala. I arrived after dark and was led down a grand hallway that opened onto a manicured lawn. Beyond an infinity pool, a fire burned, engulfing trees along the hotel’s edge. But after having hiked the highlands for several days, where the sight of smoke rising from small patches of forest is a near constant, I had recalibrated my relationship to seeing fires in nature.

A tea farmer had taught me about controlled burning: always simmering, never boiling over. I took my tea, fell asleep, and by morning, a small patch of earth just beyond the estate’s periphery was scorched, but everything else — including the view of mist-shrouded tea hills spilling into a lush valley — remained beautifully intact.

A version of this story first appeared in the April 2024 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "High Tea."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.