I Spent Years Preparing to Write About My Cousin’s Murder. The Story I Ended Up With Was Not What I Had Imagined.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

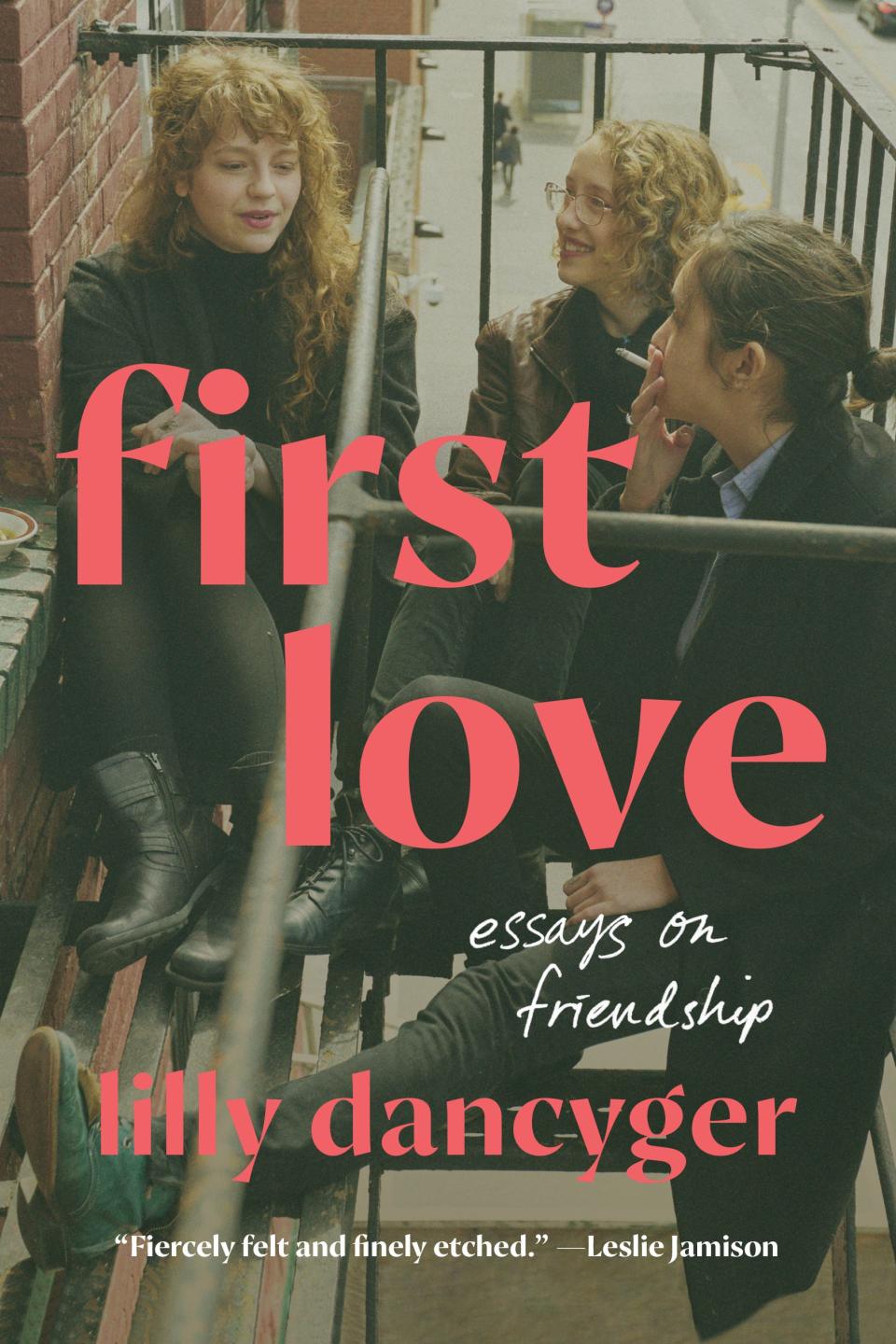

This piece is from the book First Love: Essays on Friendship by Lilly Dancyger. Copyright © 2024 by the author and reprinted with permission of The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

When I was deciding whether to attend the trial of the man who raped and murdered my cousin Sabina, I felt like I should go so that the jury would see me there. I knew how easy it would be for her to become an abstraction to them: the victim, the deceased, the body. To us—to me and my aunt and my mother and the rest of our family and her friends—she was still Sabina, still a real girl who we would never see or hug or dance with again. If we were all there, sitting on the bench behind the prosecutor, I thought, maybe the jury would be able to see that there was a real person missing. And maybe they would want to punish the man who had taken her from us.

I also thought I should go to the trial because I might want to write about it someday. I had already learned, at 23, that the page is the safest place for me to try to make sense of things that feel senseless. Telling myself I would write about what happened to Sabina someday meant I didn’t have to fully face the horror of it just yet. I could put it on a shelf, where it would wait until I was ready to arrange it into something from which I could extract some kind of meaning. And whenever that day came, I figured, the trial would be an important part of the story I would tell.

But despite these two compelling reasons that I felt I should get on a bus to Philadelphia and sit in that bright, formal room to hear the worst of human cruelty discussed in a discordantly procedural and orderly way, my body refused. Two years after her murder, my whole self was still clamped shut, bracing against the truth of what had happened to Sabina—to my first and favorite childhood playmate. The idea of sitting through detailed explanations of her final moments—seeing photos of her body in the dirt, hearing detectives and medical examiners describe the brutality enacted on her—was too much. I couldn’t even look at the mug shot of her killer or read a single news article about what he had done, let alone be in the same room as him; hear his voice, see his body move through a room or shift in a seat, so very alive, while she was not. And so I didn’t go. If I wanted to write about Sabina’s murder someday, I would have to do without the firsthand courtroom scenes.

In the meantime, I kept working on the book I had started the year before Sabina was killed, a book about my father. I approached that story like a journalist—the job I was in graduate school to prepare for while the trial was happening—interviewing people who knew my father, trying to push beyond the limits of my own memories to put together something that felt more like a capital-T True story. Thinking like a reporter while writing about my father’s heroin addiction, his art, his complicated and ill-fated relationship with my mother, and his death when I was 12 years old had provided something of a buffer between me and the ugliest parts of the story I was digging out of the earth like bones. I imagined that when I was ready to write about Sabina—someday—I might approach the story of what happened to her in a similar way: I would read transcripts of the trial I hadn’t been able to bring myself to attend; I would interview the friends Sabina had been with in the hours before she was killed, drinking champagne on a Philadelphia rooftop. I would re-create that final evening until it felt almost like I had been there, standing next to her while she laughed for the very last time. Someday, when I was ready, I would finally look directly at the truth of the way that night ended. And somehow, though I wasn’t quite sure how yet, this would help me grieve.

When David Kushner’s memoir Alligator Candy came out in 2016—six years after Sabina’s murder, four years after the trial I didn’t attend—it sounded like a potential model for the story I still wasn’t ready to write. In Alligator Candy, Kushner, a reporter, revisits the disappearance and murder of his brother Jon when the two were kids in 1970s Florida, attempting to make sense of his life’s defining tragedy using the tools of his trade. I thought it might help me start thinking about how to approach Sabina’s story, while I waited for the emotional fortitude to shore itself up in me.

I got 94 pages in—to a scene where Kushner goes to the library to read the news reports about his brother’s death for the first time—when I started to feel seasick, like the room was heaving up and down around me. This scene described something I still had not been able to do: allow the vague looming darkness to settle into the familiar shape of a news story. I squeezed my eyes shut and closed the book, noting matter-of-factly that I wasn’t ready to even read murder stories yet, let alone write one.

I continued to buy what I thought of as “murder memoirs” when they came out, which they did with increasing frequency over the next few years—a trend later identified as “true-crime memoir,” which felt at the time like a pointed reminder of what I couldn’t yet face. I bought Carolyn Murnick’s The Hot One, Sarah Perry’s After the Eclipse, Rose Andersen’s The Heart and Other Monsters, and Natasha Trethewey’s Memorial Drive when they came out between 2017 and 2020, and placed them on my bookshelf next to Alligator Candy, unopened. I added older titles to my growing collection, too: Maggie Nelson’s The Red Parts, Melanie Thernstrom’s The Dead Girl, and Justin St. Germain’s Son of a Gun. I didn’t read those either.

I couldn’t handle them yet, but I knew that eventually I would need to see how other writers had managed to write a “crime story” about something so personal and painful when, as far as I could tell from my previous associations with the genre—mostly the shows like Forensic Files and Cold Case that my mother devoured when I was a child—a good crime story required a certain degree of callousness, an ability to view cruelty with curiosity, even eagerness.

Portraying a real person on the page is always a subtle violence—reducing their multidimensional humanity, the unknowability of their inherent contradictions and mutable nature, into something flat and digestible. Even the best-rendered character on the page is only a fraction as complex as a real person. Doing this to a person who has been murdered— whose very literal humanity has already been stolen from them—feels like a larger injustice than doing it to someone who’s still living and can flout your depiction with their continued humanness. Murder already threatens to eclipse a person—it is so shocking that those of us who mourn someone who was murdered have to work to make sure the terror of their death doesn’t take up more space in our memories than the living person they once were. Writing about a murder inevitably solidifies the murder as the defining detail of a victim’s life.

So, I wondered, could I write about Sabina without reducing her to another dead girl in a story about male violence? Could I draw readers’ eyes away from the brutality and toward Sabina singing and dancing down the street on a fall day with yellow and orange leaves wet and slick under her feet? Toward the scoliosis that made it look like she was always cocking her hip, about to say something sassy—and the fact that she usually was?

Sabina came to visit me in New York when she was 20 and I was 21, and I brought her to one of my favorite dive bars. She scanned the chalkboard of bottle beers, the rows of liquor, and the taps, before asking, “Do you have any champagne?”

The bartender let out a little laugh of surprise, and said they might have some somewhere. I smiled at her and shook my head—who orders champagne at a dive bar? It felt so perfectly her—undeniably and unapologetically sparklier than everyone else. Making a special occasion out of a regular afternoon.

She gave me a shy smile, explaining, “It’s the only thing I really like to drink.”

“Of course it is!” I responded, laughing and throwing my arm around her. “Only the best for Bina.”

By then the bartender had fished an unopened, frosty bottle from way in the back of the fridge, laughing, “I think this is from New Year’s.”

“Fuck it,” I said, “I’ll take one too.”

He poured us two wineglasses of champagne, setting mine next to my whiskey soda, and we clinked our glasses and said a cheers to each other and to the day.

Could I make moments like that as vivid in a story about her as the violence they all lead back to?

When Truman Capote first pitched a story about the 1959 murders of four members of the Clutter family—Herb and Bonnie, and their teenage children Nancy and Kenyon—to his editor at the New Yorker, he described a story about the impact the crime had on the small town of Holcomb, Kansas. It was going to be about the victims, he said. Despite this stated aim, the resulting book, In Cold Blood, devotes more than twice as many pages to the depiction of the murderer, Perry Smith (and, to a lesser extent, his partner, Dick Hickock), as it does to anyone else. The Clutters are relatively thin characters, each reduced to an archetype: the hardworking father, the nervous mother, the popular daughter, the rambunctious son. The all-American family, a stock cast that could easily be swapped out for another. Meanwhile, Perry is given emotional depth, complexity, development.

Capote was not the first person to write about crime—not even the first person to write about it in an immersive, narrative style. But, as true-crime expert Justin St. Germain puts it in his book Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, “Capote spiked a vein, and out came a stream of imitators, a whole bloody genre, one of the most popular forms of American nonfiction: true crime.” And the genre he spawned has replicated his project’s central contradiction over and over again: No matter how sincere the intention to center the victim, the killer is a black hole, pulling focus to himself. Murderers are enthralling in their aberration, and made even more alluring and terrifying by the glimpses of recognizable humanity that confirm they could be almost anyone. If we as a society are captivated by murder stories (which we undeniably are), it’s no surprise that our fascination tends to focus on the most active and defining participant—the one who actually does the deed.

Many true-crime books (and shows, and podcasts) are also devoted to the second most active character in a story of murder: the investigator. True crime as we know it today is the land of sleuths, both professional and amateur—from the older shows my mom used to watch on A&E to their modern heirs like Making a Murder and The Jinx, from books like I’ll Be Gone in the Dark and We Keep the Dead Close to podcasts like Serial and In the Dark. Fans of the genre, having internalized the methods and perspectives of professional investigators, have begun taking on the role themselves, sometimes solving crimes that have stumped law enforcement (or that law enforcement couldn’t be bothered to investigate with the vigor that police-valorizing true crime has advertised).

In sleuth-focused true crime, the detective or prosecutor becomes a stand-in for the reader or viewer as we try to understand how such a thing could have happened. They, more than the murderer, are our best chance at ever getting an answer to the maddening question of “why,” because they’re asking it, too. Their doggedness and cleverness and ultimate defeat of the killer are also the security blanket of true crime—assuring us that we are safe, that the monster will always meet his match in the end.

If In Cold Blood spawned the true-crime genre as a whole, then Helter Skelter, the 1974 account of the Manson murders written by the prosecutor who handled the case, Vincent Bugliosi (with Curt Gentry), set it on the investigation-focused path it’s largely stayed on since. Helter Skelter opens on the morning of Aug. 9, 1969, when the bodies of Sharon Tate, Abigail Folger, Voytek Frykowski, Jay Sebring, and Steven Parent are discovered in the house on Cielo Drive that Tate shared with her husband, Roman Polanski—the audience enters the story at the moment it becomes an investigation. From there, the book follows a detailed timeline of police arriving at the scene; when each new clue was discovered, missed, misinterpreted, and finally put into context; and how the mystery was eventually solved and the killers brought to justice. Even the brief attempts to humanize the victims early in the narrative are couched in the perspective of the investigation, overshadowed by the crime. Brief passages about Tate, Folger, Frykowski, Sebring, and Parent—about them as living people with families and interests and plans for the future—are folded into the details of their autopsy reports, each one ending with the manner of death, presented in clinical terms. There’s a self-awareness to this technique, an acknowledgment that once we’ve encountered them first as bloody corpses, it’s impossible ever to see these people as fully alive; as anything other than murder victims.

The victim, by comparison to the fascinating murderer and dynamic investigator, tends to be the least interesting character in a murder story. She is passive; the main action of the story is something done to her, not something she does. And after her death, which is when the majority of the action in true-crime stories takes place, she is offstage—only the looming specter of a snuffed-out smile—while the active characters play out the rest of the story. She is less a character, more an implicit threat: She could be you, or your daughter, or your cousin.

It is important to note, too, that the victim is representative not of just any woman, but almost always specifically a pretty young white woman. A Nancy Clutter or a Sharon Tate. The idea of the young white woman as a symbol of innocence and goodness under constant threat from vague and ever-present danger has been part of America’s social fabric since frontier times and warnings of “Indian scalpers.” White women’s innocence has been an excuse for boundless brutality against Black men since slavery. It remains the easiest commodity to whip white audiences into a protective frenzy over. It is the bread and butter of true crime.

Sabina was mixed-race (white and Filipino), with brown skin, but she still got the Dead White Girl treatment from the Philadelphia media. Cynically, or realistically, I assume the public was so interested in her story at least in part because she had her white Irish American mother’s last name; because it was her mother (my aunt) shown crying on the evening news. But also because the specific circumstance of her murder—a random attack by a stranger on a city street after dark—is one of America’s favorite fears. Most female murder victims are killed by men they know. But a stranger killing is easier to imagine as imminent—lends itself better to dramatic music and goosebumps that might be the chill of the evening air or might be danger itself. In short: It’s more titillating.

St. Germain posits that the shift in In Cold Blood’s focus happened because while Capote never met the Clutters, having arrived in Holcomb after their deaths, he interviewed Smith at length over the course of several years. And over the course of those interviews, Capote became fascinated with Smith, came to identify with him, maybe even fell in love with him. In one form or another, I think, the same thing happens to almost everyone who sets out to write true crime. These stories are always written after the fact, when the victim is already gone, making it impossible for a writer to portray her as anything other than a memory, a stand-in for the reader or the reader’s daughter, a symbol of goodness. The killer or the investigator, however, is still there—still active in the story. Still a mystery to unravel, a source to interview. It’s no wonder then that the murder victim is rarely successfully centered in true-crime stories: Ultimately, no matter how fervently authors or producers proclaim otherwise, the story isn’t really about her at all. Not, at least, when told from the perspective of someone who never knew her as anything other than a murder victim.

As I considered the inevitability of this trap, I became convinced that the murder memoirs on my shelves held the promise of the only exception—these were murder stories told by people who knew the victims as people first. Maybe, I thought, only someone who knew the victim could ever write a true-crime story that didn’t get sucked into the black hole of the killer, or fall back on the easy framework of the investigation. Maybe, when I was ready, these books would show me how to pull off the impossible: a murder story that doesn’t further abuse the victim by reducing them to the violence of their death.

In a 2017 essay in Slate, culture columnist Laura Miller identified true-crime memoir as a trend and highlighted a pitfall that’s adjacent to, but slightly different from, the old problem with true crime in general: Rather than sidelining the murder victim in favor of a murderer or an investigator, Miller argues that true-crime memoirists center themselves too much. I bristled when I first read this accusation four years after it was published—still doing cautious background research for a story I wasn’t quite ready to write. It sounded to me like another version of the tired complaint that memoirists are self-absorbed navel gazers. At the same time, though, I felt a flash of a new apprehension: Would writing about my grief over her death make Sabina’s murder all about me?

I have seen the way people cling to tragedies that are not really theirs: remembering a friendship as much closer than it was with a person who has died, soaking up sympathy like a thirsty houseplant. The cousin relationship is not as clear-cut as sisters or even best friends, and ever since Sabina’s death I’ve struggled to articulate that we weren’t the kind of cousins who barely knew each other and happened to end up in the same place during holidays; that I loved her deep in the pit of my being, and so her death cut that deep too. That I felt as strongly for her when she was alive as I do now that she’s gone. So how to write about her death without the appearance of tragedy-seeking? How to write about my grief for her without claiming it as primary, without overshadowing the grief of her mother, my aunt? I talked to my Aunt Rachel about this concern and she waved it off, assuring me that my own grief is mine to express. But still.

Miller’s essay complicated the ethical hierarchy I’d created in my mind—now I was confronted with the possibility that a memoir about murder could be just as exploitative as any other true-crime story. And I realized that my hierarchies and suspicions and all of the plans and fears about what kind of story I might or might not write would remain theoretical as long as the murder memoirs I’d been collecting for years sat unread on my shelf. That I could ask these questions in the hypothetical forever, but would never figure out whether it was possible to tell a non-exploitative murder story until I took the leap and started reading and writing.

Eleven years after Sabina was killed, five years after my first attempt to read a murder memoir, I read Rose Andersen’s The Heart and Other Monsters, about the death of her younger sister Sarah, which appears at first to be an accidental overdose but turns out to be—maybe—murder. Miller’s qualms about true-crime memoir struck a nerve for me, undeniably. But I swung back toward defiance while reading The Heart and Other Monsters. Yes, Andersen centers herself in the story, I thought; and why shouldn’t she? The book is about what it was like to live with, and lose, her vibrant, troubled baby sister. It feels right that she be the one to write a record of her sister—her life and her death. And Sarah Andersen is so much more multidimensional on the page than any murder victim in a traditional true-crime story. It is a story about her, not the man Rose suspects of killing her, not the cops that caught her case.

The book was hard to read. There were moments that called up unwanted mental images of Sabina’s bruised body, and of her smiling face; poignant and painful articulations of the way that every happy memory of a person who was murdered becomes tainted, the shadow of the way they died at the edge of every image. I cried a few times, but I didn’t get that seasick feeling and have to stop this time. So I picked up the next murder memoir on my shelf, and then the next, and then the next.

In Memorial Drive, Natasha Trethewey’s memoir about her mother, who was shot by her abusive ex-husband, Trethewey tells the reader right at the start that it took her almost 30 years to return to the house where her mother was killed. It took her that long to be able to face what happened. I felt a little bit of relief, then. Eleven years had felt like a long time to still barely be able to read stories about murder, let alone try to write the story of Sabina’s. It was 10 years after my father’s death that I started writing about him; that felt like the inevitable amount of time. Like a deadline. But maybe it would take longer this time, and maybe that was okay.

The question of who killed Sarah Perry’s mother looms large in her memoir, After the Eclipse, and isn’t answered until nearly 250 pages in. As I read, identifying with Perry as she tried to make sense of this unfathomable and traumatic loss, I’m a little ashamed to admit, I also became invested in the mystery. I didn’t want to be a voyeur, to be like everyone else, collecting clues and making my own guesses as to who might’ve done it. But also, Sarah Perry is a skilled writer who wove a compelling narrative. I understood, logically, that she knew what she was doing by not revealing the killer’s identity until the point in the story when she learned it herself, 12 years after her mother’s death. She wanted the reader to feel the infuriating empty space, the endless possibilities of danger. She wanted the reader to want to know. But even as I moved through the story in exactly the way I believe the author wanted me to, I also felt complicit. Maybe she wanted that, too.

While reading Maggie Nelson’s The Red Parts, about her aunt’s murder and the trial, 36 years later, of the killer, I recognized glimmers of the type of scenes I might have written if I had forced myself to sit through the trial of Sabina’s killer. Nelson describes the “little methods” she develops to be able to look at the autopsy photos: “Each time an image appears I look at it quickly, opening and closing my eyes like a shutter. Then I look a little longer, in increments, until my eyes can stay open.” And the way her mother hunches over in her seat, “her chest hollowed out, her whole body becoming more and more of a husk.”

As I read these memoirs and half a dozen more, I was awed by the authors’ ability to charge ahead into such dark and terrible woods. As I suspected they would be, they were able to avoid the classic true-crime trap of sidelining the victims in favor of the more active characters because, unlike Capote and Bugliosi and every other writer or producer who has told a crime story centered on either the killer or the cops, they didn’t enter the story after the victim was offstage. They were able to bring their loved ones to life on the page through their own memories, and to keep the focus on them, because their investment in the story was genuinely tied to the person they’d lost, not the intrigue or shock value of the crime.

But they also included the details that audiences have come to expect from crime stories. They read police and autopsy reports, painstakingly recreating and describing their loved ones’ terrified last moments; putting into words all of the unspeakable imaginings anyone close to a murder victim lives with, about what they must have thought, and felt, at the end. They walked into police stations and held in their hands articles of clothing stained with the blood of people they loved. They transformed the killers who had marred their lives forever into characters, with backstories and traumas of their own. In my awe, it was very clear to me that I was still not ready to do any of these things.

I still didn’t feel physically capable of looking closely enough at the details of Sabina’s murder to tell this kind of story about it—at least to tell it effectively, with the kind of brazenness of these writers, who don’t let their readers slip into the comforting lull of the traditional true-crime sleuth story. They prevent their loved ones from becoming passive dead girls in entertaining stories about killers and cops by keeping the horror, the too-real reality, brimming on the surface. They force themselves to look, and in turn they don’t let their readers look away. I didn’t have the fortitude to tell a story like that. And, I finally realized, I didn’t want to.

I started to wonder whether there was a different kind of story I could tell instead.

If I’d written the kind of book I initially thought I would write someday, I would have set out at some point to learn about Sabina’s killer. I would go digging into his childhood, looking for what put such violence into him. I would wonder if a grain of hurt had settled deep in his heart, collecting layer upon layer of anger like a hideous pearl until it became too big to contain. I would pose the question of whether he hated women specifically, or was just a coward who liked his odds against a 20-year-old girl better than against another man when the rage in him demanded a target.

But I don’t want to know these things. I don’t care about his childhood or what was going through his mind that June night when he first spotted Sabina and started following her, or during what came next. I don’t ever need to know so much as what his voice sounds like. Don’t need to let him become human for me; a character more defined than a fairy-tale wolf, a personification of evil. Nothing that could have happened in his life would make what he did make any sense, and the idea of searching for a reason feels too close to inviting sympathy for him—in myself or in a reader.

It is possible to write a true-crime memoir without offering undue grace to the killer. In fact, most of the ones I read stand firm in their refusal to do so. The Heart and Other Monsters is divided into five parts, and the man who may have killed Andersen’s sister is not given a name until part IV, referred to until then only as “the Man.” He is part of Sarah Andersen’s story, not the other way around. And Perry writes about her decision not to interview her mother’s killer for After the Eclipse: “To be in conversation with someone, you must cooperate with them, however briefly, and I have no wish to cooperate with him.” (I felt such immense relief reading that line—I had been bracing for such an interview since she brought up the possibility earlier in the story, and wanting desperately for her to spare herself.) But even these authors’ demonstrations of how to keep the murderer out of the center of a murder story felt like more attention than I was willing to give. I don’t even want to know enough about Sabina’s killer to hate him with more precision than I already do. All I need to know about him is that he will be in prison until he dies.

It’s been 13 years now since Sabina’s death, and I still can’t bring myself to wade all the way into the horror of what happened to her. What’s changed, though, is that I’ve stopped waiting to be able to, stopped anticipating that someday I will have to. I feel instead a self-protective impulse, a stubborn unwillingness to shine a bright light on the most horrible parts of this story.

In all of these murder memoirs I read, there was a sense that the writer felt it was their duty to look directly at the ugly truth. Several state this outright; in others it’s present as an undercurrent, in the way the writers keep pushing forward despite nightmares, nausea, and visceral urges to flee. I felt this sense of duty when I was investigating my father’s life, reading his journals and letters, sitting through tearful conversations with my mother and stilted ones with people who had betrayed and been betrayed by my father during the course of his heroin addiction. I had to keep going because I had convinced myself that if I looked at every detail, including the most painful ones, they would arrange themselves into a constellation of him. Maybe that’s part of why I’m not driven to handle this story in the same way—I’ve already written an investigative memoir, wringing every detail I could out of letters, journals, and interviews, trying to conjure my father back to life. I’ve already reached the end of that road and found myself still alone, my father still dead. So I can’t convince myself it would work if I tried again.

“I have spent years conjuring her body,” Andersen writes of her sister, “have envisioned myself next to her as she died again and again.” I understand this impulse. I have three dried seedpods from a tree in the lot where Sabina died, and sometimes I look at them and hope that in the last moments of her life, she was looking up at this tree, not at the face of a monster. That as she was fading into unconsciousness, she could no longer feel the pain in her body, or the fear—that maybe she felt even just a second of peace. I have looked at these seedpods and tried to transport myself into this final moment through them, to crouch in the dirt beside her and smooth her hair out of her face, wipe the tears from her cheeks, and whisper in her ear, It’s OK, you’re OK, I’m so sorry. I love you. But for whatever reason, the seedpods are enough for me to do this. I don’t need the autopsy report, the trial transcripts, the sound of a killer’s voice.

I spent years preparing myself to write a crime story, waiting for the desire to know more about Sabina’s murder to bubble up in me. I expected it, but it hasn’t arrived. When I finally sat down to write about Sabina, the story that came out was not about murder at all. It was a love story.