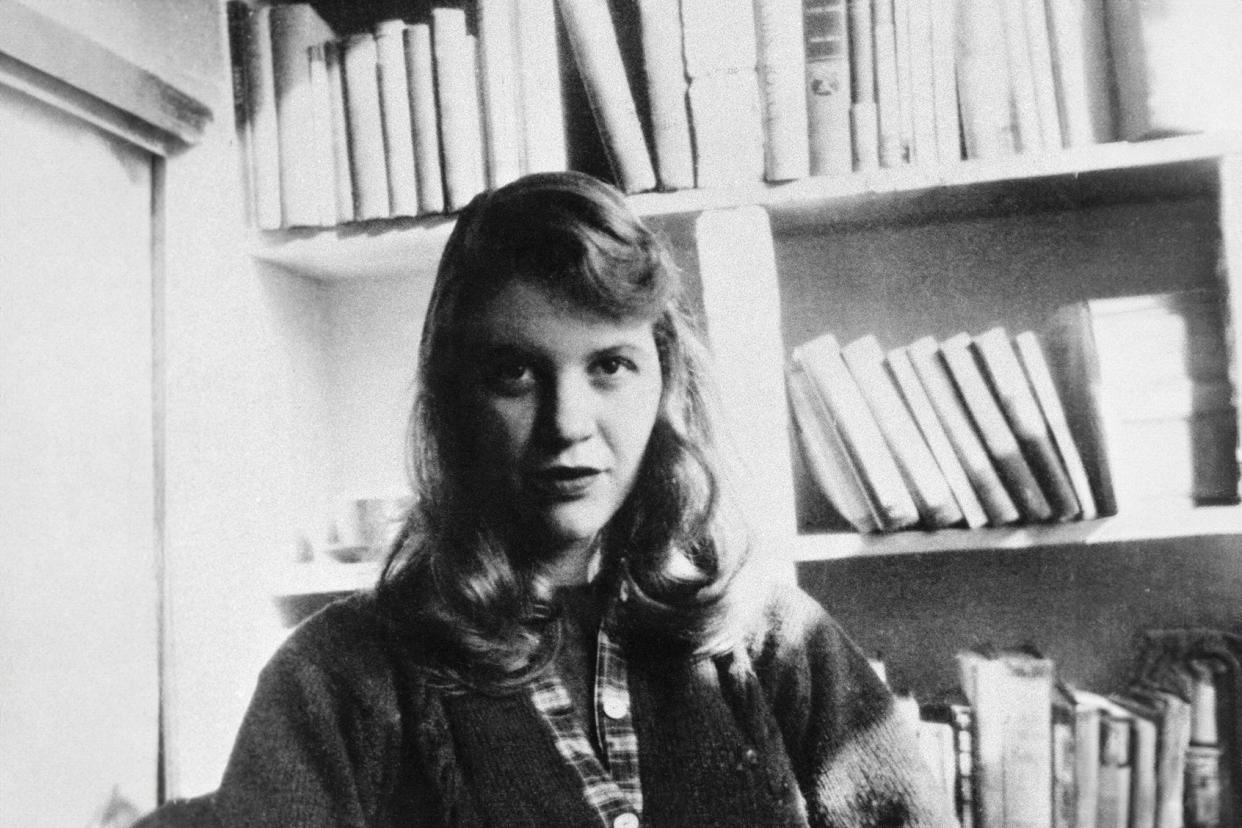

Reading Sylvia Plath and my dead friend’s Instagram

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

From the book "FIRST LOVE: Essays on Friendship" by Lilly Dancyger. Copyright © 2024 by Lilly Dancyger. Published by The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Heather had invited me over to her apartment in Inwood several times in the last year or so, but for one reason or another, the scheduling had never worked out. We kept promising each other, “soon.” Now I was finally here, for the first time, to help pack up her things. She’d been dead for a week.

I scanned the stacks of books teetering against one wall, not on shelves but layered like bricks, and a slim off-white spine called to me: Sylvia Plath’s "Ariel." It felt like a morbidly appropriate souvenir of this day.

Heather was a definite Plath Girl as a teenager. I was too — just two of countless teenage girls since the ’60s to proclaim our love for the bracing and violent "Ariel" poems, and "The Bell Jar," Plath’s fictionalized account of her first mental breakdown, suicide attempt and institutionalization — a not-at-all-subtle way of making sure the world knew we were in pain. “I just really identify with Esther Greenwood,” we’d tell adults: a threat. Claiming Plath was a way to elevate our teenage sadness from pedestrian and expected and cliché to literary, tragic, romantic. To tie our early-aughts angst to a dignified and important history.

We weren’t the first or the last teenage girls to romanticize sadness and tragedy, of course. Before Plath there were Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson and the Brontë sisters, each with her own morose devotees.

More recently, there was the “sad girl aesthetic” era of Tumblr — young women posting photos of themselves with mascara tears running down their cheeks, or black-and-white selfies in which they’re staring mournfully into the distance, with quotes about depression and existential ennui for captions. The social media sad girl has a very specific tone — the inherent vulnerability of expressing sadness coated in a protective gloss of sardonic humor and irony. Alongside the dramatic crying selfies, sad girl Tumblr pages were full of simple, morose statements like “I hate my life” written in glittery pink cursive or pastels, the cheerful presentation clashing with the message to strike the discordant note central to so much internet humor.

* * *

When I got home from packing up Heather’s apartment, I wrote “Heather’s” on the title page of her copy of “Ariel” in small, neat script, as if I could forget. I started to read it, but only got as far as “Lady Lazarus,” five poems in — to the line about meaning to “last it out and not come back at all” — before the connection to Heather felt too painfully literal. I closed the worn paperback and slid it onto a shelf, where it would sit unopened for years.

The tragedy of her death mingling with the brilliance of her poetry made Plath an icon, but it also made her sadness and her tragic end her defining traits. It wasn’t until decades later that a new generation of Plath scholars would advocate for dimension in readings of her work — pushing fans to celebrate her birthday rather than her death date, publishing analyses and close readings of her poems about bees rather than only the ones that evoke death and violence. “The public perception of Plath as a witchy death-goddess had been born and would not soon die,” Plath biographer Heather Clark writes.

I don’t want to flatten Heather in this way — as sure as I am that she would absolutely relish the title “witchy death-goddess.” It’s too easy to remember her as a sad girl because of her sad death. To rewrite her life, starting with the end. But there was so much more to her than that.

She carried herself with the ease of a beautiful woman, swinging her hips and not blushing at raunchy jokes, when the rest of us were still awkward girls.

She was proud of being Jewish and proud of being Chinese and she delighted in the exploration of both sides of her heritage, through study and food and fashion — cooking noodle kugel in a qipao and calling herself a “Lower East Side special.”

She had this guffawing laugh — not the cackle that cracked the air around her when someone else said something funny, but a single goofy exhaled chuckle, the laugh she laughed after she said something she thought was funny. It was so totally incongruous with the hot girl it emanated from, so unexpectedly and endearingly dopey, you couldn’t help but laugh at her laughing at her own joke.

These are the things I most want to remember about Heather.

But the sadness was such a big part of who she was, of how she saw herself and how she moved through the world, it would be as much a disservice to her to gloss over it as it would be to let it take over my memory of her completely.

* * *

The first time Heather called me in the middle of the night saying she wanted to kill herself, I treated it like an emergency.

I woke up to my phone buzzing on the table next to my bed, confused. It was past three in the morning. I blinked the sleep from my eyes and cleared my throat before answering urgently, “Hello?”

On the other side of the line, Heather sobbed. When she finally spoke, it was more of a wail, “I wanna die!”

I offered to come to her, asked if she wanted to come to me, asked if I should call an ambulance, but I realized quickly that she didn’t want to be rescued, she just wanted to be heard. She wanted someone to know how much she was hurting. So I listened. I got back into bed and lay down, but didn’t close my eyes.

“I love you,” I said. “I’m so glad you’re alive. I’m so sorry.”

Eventually her sobs slowed to sniffles. I asked if she thought she’d be able to sleep and she sighed, “Yeah.” When I woke up again a few hours later, there was a text from her: “Thanks. Feeling better. Love you.